A pilgrim finds God on a Spanish mountainside

‘I had gone seeking sources of reverence, and rather to my surprise I found them’

So I decided to go on pilgrimage.

All my life I have laboured in the vineyard of the evangelical Christian world. My calling has been to publish Christian literature, encouraging and shaping and polishing, attending to the business of books and ensuring the wheels turn smoothly. For over 25 years I have also been a local preacher (a Reader, for Anglicans), deeply involved in the training and nurture of the Body of Christ.

But something was missing. Any minister knows how easy it is to get so caught up in the service of the Almighty that you ignore the Godward aspect. I had grown complacent. I wished, like a lobster, to shuck off my shell. I longed for new sources of reverence. If God was willing to speak to me I wanted to put myself in a state of mind to listen.

Over 200,000 pilgrims walked the Camino in 2013.

The Camino de Santiago, the Way of St James, seemed ideal. A pilgrimage route since the 9th century, it winds towards Santiago de Compostela over the mountains and plains of northern Spain for nearly 500 miles (or rather more than the distance from Melbourne to Adelaide). Its popularity diminished after WWII, but since the turn of the century the idea of pilgrimage has been rediscovered: over 200,000 pilgrims walked the Camino in 2013, the year of my own journey. But there were risks. I don’t speak Spanish. I might fall off something. Inexpensive hostels dot the route, but you cannot book, so you set off each morning not knowing where you will lay your head. I’m in my sixties, with dodgy knees and a heart condition: could my creaking frame cope?

My generous employers, Lion Hudson of Oxford, had given me a sabbatical. One September morning I caught the early express from Hastings, my home town on England’s south coast, to Stansted Airport and a plane to Biarritz. From there a little train winds up through the foothills of the Pyrenees and the small, walled border town of St Jean Pied-de-Port: St John’s at the Foot of the Pass.

Within ten minutes I was puffing. Sweat poured down my face as I gasped the thyme-scented air.

The following morning dawned cool and cheerful. Joining a steady stream of pilgrims I settled my pack on my shoulders and stepped out jauntily along the metalled road towards Spain. After a few hundred yards the route abruptly veered left and upwards, disappearing into the scrub, and I started to climb over the mountains. Within ten minutes I was puffing. Sweat poured down my face as I gasped the thyme-scented air, hauling myself up from one thorny shrub to another. I stopped to drink from my water bag, and overhead a distant circling movement caught my eye: a griffon vulture. These huge birds tidy up the sheep in the mountain pastures, but it was easy to imagine they would appreciate a change in diet.

If the ascent was bad, the eventual descent on the Spanish side was worse, as I slipped on sliding scree from one smooth beech trunk to the next. When I finally stood swaying in the entrance hall of the waiting hostel my confidence was shredded. What had I taken on?

Over the course of the ensuing weeks I gradually grew road-hardened. Breaking out my rusty language skills I made friends with various French pilgrims, spending hours in conversation and filling my notebook with oddments of vocabulary. I met two sisters from California and a trio of US Marines: after a few hours’ walking you exhaust the niceties and start to talk in earnest, friendships forming quickly and durably.

My younger, snottier self would have dismissed all [shrines] as mere folk religion, but I paused before one shrine and found myself weeping: this was a place of simple holiness.

I had gone seeking sources of reverence, and rather to my surprise I found them. The Camino features many wayside shrines, some to pilgrims who had succumbed to heart attacks or lightning strikes or traffic accidents. Those who pass augment these roadside crosses with messages and photos, jewellery and pebbles. My younger, snottier self would have dismissed all as mere folk religion, but I paused before one shrine and found myself weeping: this was a place of simple holiness, of reaching out, a hand outstretched towards the divine. According to surveys a majority of pilgrims are not committed Christians, but this doesn’t mean they are not spiritually aware.

This perception came to sharp focus at the Cruz de Ferro, the tall Iron Cross on a wooden pillar which stands in the mountains of Galicia at the highest point of the Camino. The tradition is that you bring with you a stone from your homeland to place at the foot of the Cross, and I carried a pebble from Hastings beach on which my stepdaughter Hebe had painted the coquille St Jacques, the scallop shell symbol of the Way of St James.

The site is holy, for here the banker and the shop girl stand equal before the Cross and leave a trace of their presence, their fears and hopes, ambitions and dreams.

The years of pilgrims, each bearing their stone, has left a cairn stretching tens of yards. Emerging from the swirling mist at the top of a steep climb, the Cruz de Ferro is a mess. Stones, watches, bracelets, scarfs, boots, belts, photo frames, figurines: all kinds of mementos. In the fog every surface is drenched with moisture. Yet the site is holy, for here the banker and the shop girl stand equal before the Cross and leave a trace of their presence, their fears and hopes, ambitions and dreams.

In The Way, a fine film starring Martin Sheen about walking the Camino, each of the characters approaches the Iron Cross and says a prayer. The previous night Jim, one of the Marines, asked me what he should say. I looked at him in some surprise, then realised he needed a script. What words might a tough, worldly, experienced man in his fifties, for whom the realm of the spirit is unfamiliar territory, be willing to utter? After a few moments’ thought I wrote the following:

Holy Spirit of God

With this stone I express my past, my present and my future.

I acknowledge before you that things have not gone as planned. Sometimes I have been at fault.

Take all that I have been, and all that I can be, and make of me the jewel you had in mind.

Amen

I gave Jim the page, torn from my notebook. He was pleased. The following day he and the Californian sisters sat opposite the Cruz an hour or so after I had passed by, and drank a bottle or two of wine together. Months later he sent me a scan of the scrap of paper, creased from his wallet.

St James may or may not have been present, but the Holy Spirit most certainly was.

And so, in due course, I reached Santiago, after 32 days of steady walking. In the Cathedral of St James lies the crypt, below the altar, where the saint’s presumed remains are interred. Early one morning I made my way down the steps while no one was around. I do not subscribe to the veneration of saints, and the identity of the body in the marble sarcophagus is open to question. But that quiet place was redolent with prayer, and I sank to my knees and worshipped: St James may or may not have been present, but the Holy Spirit most certainly was.

I learned, I think, two primary truths from my pilgrimage. First, the less you carry the easier it is to travel. For years my wife Pen Wilcock and I have been streamlining, disposing of books and clothes, heirlooms and ornaments. This needs to be accompanied by a metaphorical stripping, of hang-ups and anxieties and worries about status. The more firmly you grasp your pilgrim identity, the simpler this grows. A pilgrim learns to tread lightly upon the earth.

Fictions about yourself, your significance, your religion: all get in the way of truth.

The other truth: you learn to dispense with lies. Fictions about yourself, your significance, your religion: all get in the way of truth. Walking across the Meseta, the vast and infinitely boring central plain of Spain, allows a wholesale purging of illusion: the process is not pleasant, but it allows you to acknowledge both your smallness in that enormous horizon, and your preciousness to the One who made both.

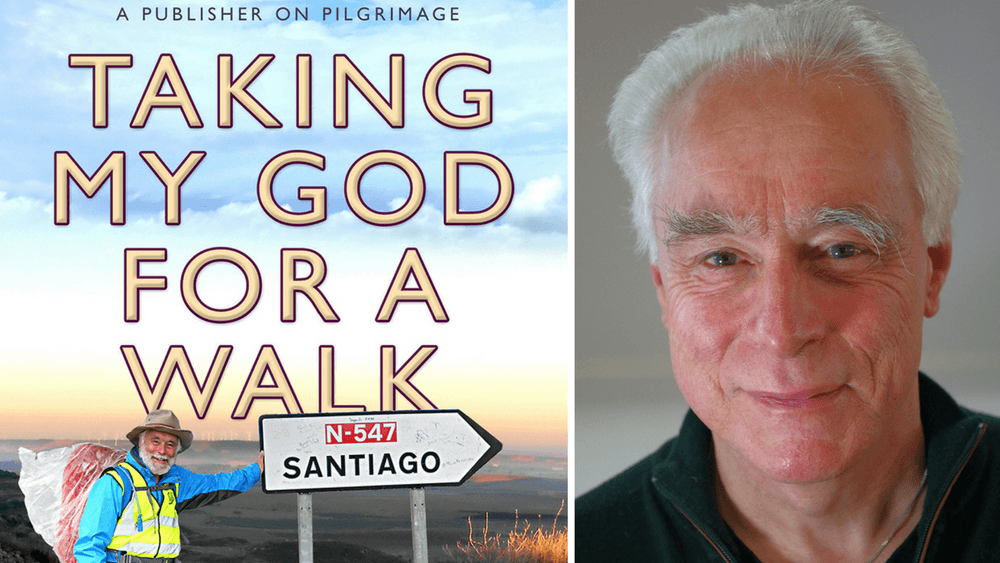

Tony Collins is an editor with Lion Hudson, and founder of Monarch Books and Lion Fiction. Taking My God for a Walk, an account of walking the Camino de Santiago, is published by Monarch and distributed in Australia by Koorong.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?