John Chau’s death raises serious questions

‘The days when Westerners were the guardians of the gospel are gone’

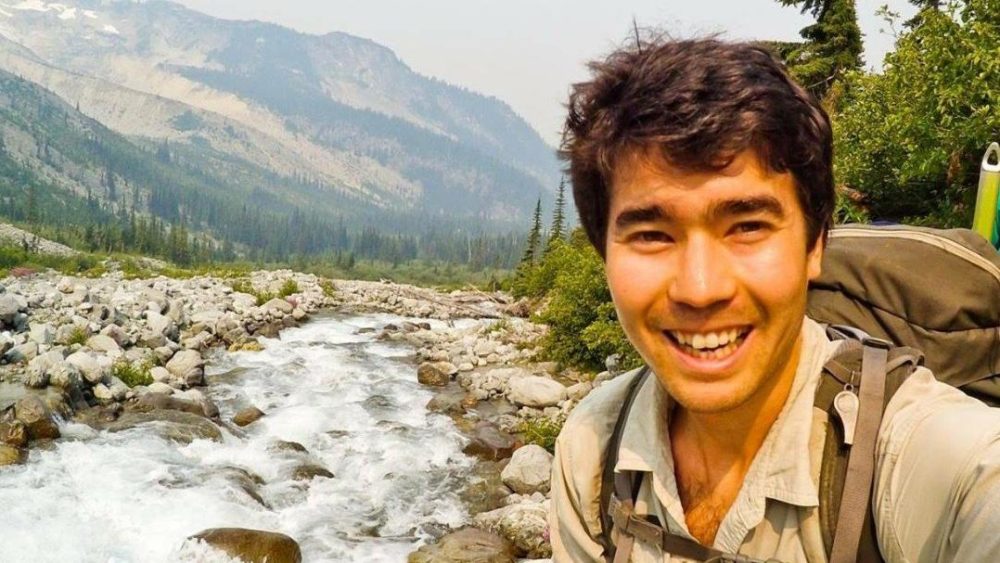

John Chau’s death raises serious questions for Christian missionaries. Multiple narratives have emerged since 26-year-old American missionary John Allen Chau was killed two weeks ago when interacting with the people of North Sentinel, a remote island between India and South East Asia. He has been lauded as a missionary hero and scorned as a fool and religious zealot. His actions have been portrayed as lovingly purposeful, and also as profoundly unloving because of the existential threat that contact poses to the Sentinelese people .

This is a contested case among Christians because the Sentinelese push the limits of our thinking. We believe that Jesus the Messiah is the “desire of the nations,” that through him every human community, indeed planet Earth itself, can be honoured and enjoy fullness of life. The received wisdom is for missionaries to cross cultures by getting alongside a community, learning its language, appreciating its culture and, somewhere along the way, we hope for encounter with Jesus. But what happens when this scenario gets complicated — when our presence is threatening, for example? If people need to be “reached” but our received wisdom can’t easily be applied, what then?

This is a conversation about how we pursue the Great Commission. Jesus entrusted his work to sinful, foolish humans, and is able to glorify his Father even through our faulty efforts. However, this cannot keep us from interrogating our history and our present. Seeking to examine and reform ourselves is an exercise of the Spirit – that is, of growing in love, peacemaking, kindness, gentleness and self-control. We need to be able to talk about actions, about what is wise and appropriate. We need to be able to identify and do away with harmful approaches. This is the work of missiology.

Love

The Gospel of Matthew gives us not just a Great Commission, but a Great Commandment: to love God and neighbour. Jesus’ own definition of love – to treat others as we would hope to be treated – pushes us beyond our good intentions, and calls us to ask what actions are truly in the best interests of the other. So, what are the best interests of the Sentinelese?

The Sentinelese are one of four indigenous nations in the Andaman Islands, all of which have been traumatised in different ways by disease, violence, and encroachment, beginning with the British Empire in 1789. One of these nations, the Great Andamanese, once comprised 10 tribes, each with its own language. Their numbers have been reduced from perhaps 5000 to just 50. A fifth nation, the Jangil, was completely wiped out early last century.

As Christians, we see at least two needs that, in regard to the Sentinelese, appear to compete with one another. There is the need to encounter Jesus, and there is the need to promote life. If the gospel comes to the Sentinelese in a way that is likely to cause the destruction of their lives and culture, can it be said to be loving?

The Sentinelese may lack immunity to common illnesses that we are untroubled by. We now know that John Chau had invested time in planning for his visit, and had taken measures he believed would minimise infection. Even if this were known to guarantee their safety, however, the destabilisation of contact is not limited to infectious diseases, nor to one individual. This consideration cannot be sidelined by someone’s desire to serve, feelings of compassion, or personal sense of calling. Love must be knowledgeable — a love that can deal with the complexity of the world we live in.

Urgency

Yet many of us experience a sense of urgency in evangelism, as perhaps John Chau did. We are compelled by two beliefs – the eternal vulnerability of those who don’t know Jesus, and his impending return. In this way of thinking, each day the Sentinelese miss the opportunity to know Christ is also a day when one of them could die and potentially face eternity without him.

However, this is not the only factor in evangelism. For example, without a relationship of mutual trust, the message goes awry. Jesus’ command is not simply to preach, but to disciple nations. The point is not so much to get the word out as to get the word across. As far as we know, the Sentinelese still know nothing of Jesus. Perhaps in God’s economy, John Chau’s sacrifice is a “grain of wheat” that will eventually result in Christian commitment. Then again, perhaps it was a setback for his message.

But who gets to determine another community’s needs anyway? We may feel an urgency ourselves, but how does this square with the concerns and desires of others?

Agency

This brings us to the question of agency. ‘The natives’ are never passively waiting to absorb what outsiders bring. They are fully responsible persons who choose to interact on their own terms. This cuts two ways: it acknowledges both “conversion” and resistance. After the trauma of British contact in the 19th century, we acknowledge that the Sentinelese have good reason to be hostile to outsiders.

To recognise agency – to attempt to see through the other’s eyes – is to love. It is not our prerogative to decide what is best for others. Our desire to proclaim Christ does not overrule the God-given agency of others. This is part of what is going on when, in the Book of Acts, the apostles depart from communities that are hostile and invest themselves in communities that are receptive, a pattern established by Jesus in Luke 10.

Does this mean the Sentinelese must be put aside when it comes to world mission? The sheer mess of these overlapping questions leaves our heads spinning. But here’s another thought.

A way forward?

When a middle-class Western Christian like me hears the call of the Great Commission, by default I assume that my role is one of leadership or pioneering. We make this assumption also at the level of the mission organisation and the Western church more broadly. We are not in the habit of looking for missionaries among majority world and indigenous believers, because world mission is something we so naturally associate with ourselves.

However, the days when Westerners were the guardians of the gospel are gone, if they ever existed. Majority world churches are now among the top missionary sending countries. This includes nearby India, as well as the island nations of Malta, Samoa and Tonga. Concern for the Sentinelese will mean engaging Christian communities such as these, where there is greater cultural or geographic proximity. It will also mean engaging indigenous Christians — those who have experienced first-hand the intergenerational trauma of colonisation. To learn how isolated tribes might relate to the Great Commission – and what is truly life-giving – may be a journey best led by communities such as these.

This is a slower path. Paul’s famous definition of love in 1 Corinthians 13 refers to both patience and perseverance — of waiting with and for one another. Yet this is also a fruitful path. We ask not only “How do we reach the unreached?” but also, “What part is to be played by each member of the global body of Christ?” Rather than sending anyone who wants to go because God in his sovereignty can use them, our desire is to see the global body of Christ being true to God’s calling, and to locate ourselves within that. This can only result in a more authentic and consistent witness to Christ. This does not bar us from pioneering work, but if we assume such a role without reference to the global church, we dishonour our brothers and sisters, and are ultimately less fruitful.

Perhaps you too have a heart for the Sentinelese. If so, have the humility to consider that you and your community might not be the ones to care for them or encounter them. King David learned that the building of God’s house belonged to a different generation. In our time, the pursuit of authentic global witness – and of best practice in mission – puts our feelings of urgency in perspective. This is uncomfortable for us, especially when we have invested so much in our own pioneer efforts.

No doubt there is still a part for us to play in the Great Commission, but after more than a century of pioneer Protestant work, we now need to discover afresh what our part may be. It is a team effort involving all our brothers and sisters worldwide. It is time to take a step back, and take stock of the global family we now find ourselves in.

Arthur Davis is coaching and mentoring staff workers in TAFES, a Tanzanian campus ministry. He and his wife Tamie Davis are part of CMS Australia and write at Meetjesusatuni.com

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?