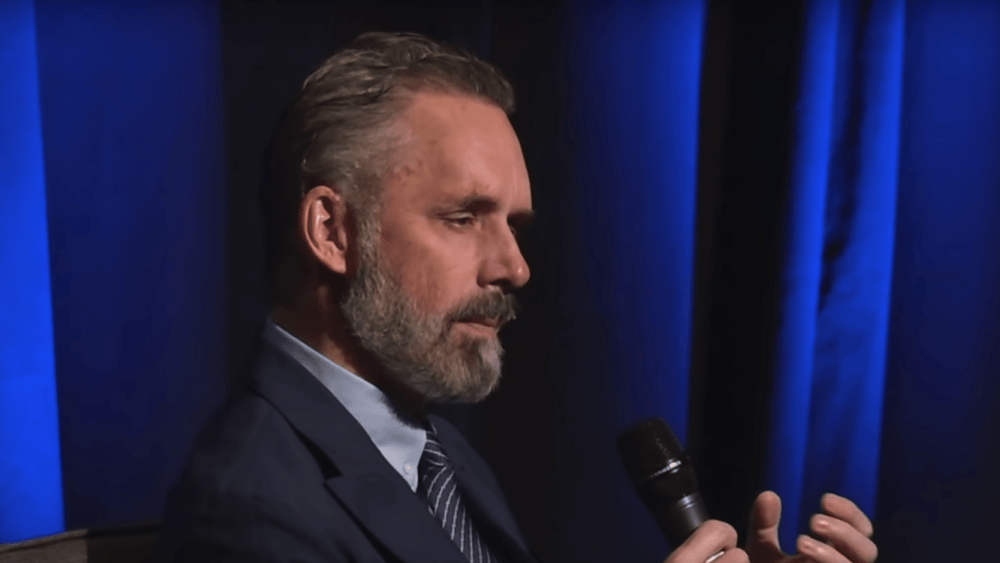

Why I'm not a Christian: Jordan Peterson

And how you might ask him about becoming one

Canadian psychologist and social commentator Jordan Peterson continues to be in conversation with religious leaders around the world – with his beliefs about belief being heard, but not discussed.

Peterson was a key speaker at the recent PragerU 2019 Summit, a conservative conference held in California. Near the start of a one-hour conversation with Peterson, PragerU founder and broadcaster Dennis Prager asked the popular and controversial speaker: “You live as if there is a God. Is that correct?”

“Who would have the audacity to claim that they believed in God?” – Jordan Peterson

Along with Peterson’s positions on politically correct language and the status of masculinity, he also has attracted international attention for his upholding of the Bible, God and Jesus. Among other fans of his philosophies, notably young men, Peterson has attracted a considerable groundswell of support from plenty of Christians. His endorsement of biblical views about good and evil, morality and living well together has contributed to this popularity, yet Peterson has never publicly claimed to be a Christian.

Peterson began his response to Prager – who is Jewish – by mentioning he’ll soon release a podcast about God, having been asked so often about that personal subject during his ’12 Rules for Life’ Australian tour earlier this year.

“I don’t like that question, so I sat and thought about it for a good while and I tried to figure out why,” Peterson told the PragerU Summit audience. “And I thought, well … who would have the audacity to claim that they believed in God? If they examined the way they lived, who would dare say that?”

“To believe, to believe in a Christian sense, to actually — this is why [philosopher Friedrich] Nietzsche said there was only ever one Christian and that was Christ — to have the audacity to claim that, means that you live it out fully. And that’s an unbearable task in some sense.”

Prager is akin to provocative Sydney talkback radio host Ray Hadley, according by Eternity editor in chief John Sandeman. A well-known broadcaster on the American Christian network Salem Media Group (which also airs other types of conservative content), Prager established PragerU as a digital media hub “to promote what is true, what is good, what is excellent, and what is noble”.

He did not interrupt Peterson’s answer or ask additional questions.

Peterson referenced Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek’s suggestion that Jesus on the cross is an example of a moment when God “lost faith”, before he proceeded to define what it means to believe.

“To be able to accept the structure of existence, the suffering that goes along with it, and the disappointment and the betrayal, and to nonetheless act properly, to aim at the good with all your heart, to dispense with the malevolence and your desire for destruction and revenge, and all of that, and to face things courageously and to tell the truth, to speak the truth and to act it out: that’s what it means to believe,” said Peterson.

“It doesn’t mean to state it; it means to act it out. And unless you act it out, you should be very careful about claiming it.”

“And so I’ve never been comfortable saying anything other than, I try to act as if God exists, because God only knows what you’d be if you truly believed.”

“So while I try to act like I believe, I never claim that I manage it.” – Jordan Peterson

Speaking passionately at this point, Peterson then distilled his view on “the central idea in Christianity – that if you were capable of believing, it would be a transfiguring event, a truly transfiguring event.”

“And I know people experience that to one degree or another, but we have no idea what the limit of that is, and we have no idea what the possibility is within each person if they lived a life that was maximally courageous and maximally truthful. … God only knows what you’d be if you believed.”

“So while I try to act like I believe, I never claim that I manage it.”

“That’s a great answer, as it happens,” affirmed Prager without responding to Peterson’s statements.

The remainder of Prager’s public conversation with Peterson covered topics of good and evil, morality and the fabric of society — without ever directly returning to Peterson’s definition of belief in God, or his view about the “audacious” claims of Christians.

Prager rightly treats Peterson as an expert in his particular fields and didn’t veer into a theological debate. But its curious that Peterson’s evident willingness to engage with biblical beliefs and truth was an opportunity for further discussion that Prager did not seize.

An ABC article, belatedly picking up on the relationship between swathes of the Christian world and Peterson, references a 2018 interview with him conducted by former Australian Deputy Prime Minister John Anderson (who is a professing Christian).

What might someone put to Peterson about his insights into Christianity?

Viewed more than 740,000 times, the video conversation is similar to the PragerU video in that most time is dedicated to Peterson’s key talking points (freedom of speech and religion; social control; personal moral responsibility; recognition of evil). Yet even when Peterson wanders squarely into Christian doctrine — Peterson argues for the “practical utility” of following the “take up your cross” message of Jesus, irrespective of any possible “metaphysical baggage” that message might demand — Anderson also does not explicitly tackle what Peterson presents.

Anderson told ABC he knows Peterson doesn’t attempt to uphold Christianity as a Christian would. But he does like that “everything [Peterson] says paves the way for a powerful reminder that we do need to consider those claims.”

A powerful reminder for Peterson himself, yet one often not considered further by the procession of leaders of biblical religions keen to discuss his worldview.

So, what might someone put to Peterson about his insights into Christianity? Perhaps as they agreed with many of them, they could challenge his conclusions.

For example, Peterson described the central idea of Christianity as a “transfiguring event” – but one unable to overcome the “unbearable task” of people trying to live fully for God.

However, it could be asked of Peterson: is it possible that someone, through belief in God through Jesus, might experience such transformation that the “unbearable task” is made bearable?

God says Peterson is right that no person can examine their own life and declare they wholeheartedly and perfectly have lived for God.

That’s a point Peterson made to Prager and it’s also the strong thrust of Psalm 14:1-3 or Romans 3:10-12 – “There is no one righteous, not even one. There is no one who understands; there is no one who seeks God. All have turned away …”

“God demonstrates His own love toward us, in that while we were yet sinners, Christ died for us.”

Peterson says it is too audacious to claim that such a depressing verdict could be overturned. Yet that’s the claim clearly linked with a man Peterson greatly admires – Jesus.

“Once you were alienated and hostile in your minds expressed in your evil actions,” writes the apostle Paul in his letter to the Colossian church. He was referring to those of us who are mortal, flawed and sinful. So, you know, that would be all of us. And, yes, that does sound terrible — for each and every one of us.

But if you read the few sentences before that statement, Paul sings the praises of Jesus – “the image of the invisible God” (Col 1:15) who made “peace through his blood on the cross” (Col 1:20).

This reference to Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection is crucial. It squarely points back to a “transfiguring event” — Peterson’s (rather loose) term.

It seems that Peterson does not fully grasp the event at the epicentre of Christian faith — an event that’s significance is somewhat detailed in Paul’s next lengthy sentence (Col 1:22-23): “But now he [Jesus Christ] has reconciled you by his physical body through his death, to present you holy, faultless, and blameless before him – if indeed you remain grounded and steadfast in the faith and are not shifted away from the hope of the gospel that you heard.”

Clearly, these are complicated ideas. They’re not easily dropped into a recorded conversation with a prominent psychologist.

But here’s another soundbite way of saying what Paul just did: grace.

Grace doesn’t take centre stage in either Prager’s or Anderson’s Peterson conversations. I wonder how many Christians have attempted to help Peterson understand the power and liberation of the potent truth that God offers salvation to anyone who has faith in Jesus. It’s an offer extended to humans who have not lived fully for God with God providing a way for them to do just that, via a wonderful gift of rescue that nobody does anything to merit.

Or, as the apostle Paul says more eloquently in his letter to the early Christian church in Ephesus: “For it is by grace you have been saved, through faith — and this is not from yourselves, it is the gift of God— not by works, so that no one can boast.” (Ephesians 2:8-9)

Peterson appears flummoxed by the failings of people to be able to live life fully for God. Fair enough. No-one has come up with a solution to that problem. Except God himself, through Jesus.

“God demonstrates His own love toward us, in that while we were yet sinners, Christ died for us.” (Romans 5:8)

Such shocking love and the unwarranted opportunity to then live rightly for God — because of what the gift of Jesus can do for any of us — is the missing piece of the jigsaw puzzle Peterson often finds himself discussing.

Maybe next time someone will jot down an “ask him about grace” question.