What a white man learned from Aboriginal Australia

Luke Richmond takes a personal look back at ‘The Intervention’

I arrived in Central Australia against the backdrop of ‘The Northern Territory Emergency Response’. Or, as it would come to be known: ‘The Intervention’.

It was a far cry from where I had grown up on the affluent Northern Beaches in Sydney.

When I thought of people living in poverty, my mind would take me to developing countries overseas.

Here I was, ready for my first job. Based out of Alice Springs, I was working in health, travelling out to Warlpiri communities (Yuendumu, Lajamanu, Willowra and Nyirripi) in remote Northern Territory.

I had taken the role thinking it would be a quick way to get experience before trying to get a job with the United Nations and working with vulnerable communities around the world. I dreamed about going to places in Africa, Asia, South America and the Middle East.

But, here, in my country’s back yard, I was completely unprepared for what I would experience.

When I thought of people living in poverty, my mind would take me to developing countries overseas. While I had read articles, and seen footage of what life was like for Indigenous Australians in remote communities, it was easier to brush it off as something that had been taken out of context.

Surely, in a country as wealthy as ours, this was impossible?

Not only was it plausible, these conditions were overt, backed up with systems that discriminate.

The Intervention (which began in the NT in 2007 and continues today under the “Stronger Futures” legislation) started as a government package aimed at gaining control of Indigenous communities which were reportedly flowing with “rivers of grog” and drugs.

What sparked The Intervention? An ABC interview with a youth worker in Mutitjulu who had defended then Indigenous Affairs Minister Mal Brough’s claim that “pedophile rings” were operating in all communities in the NT.

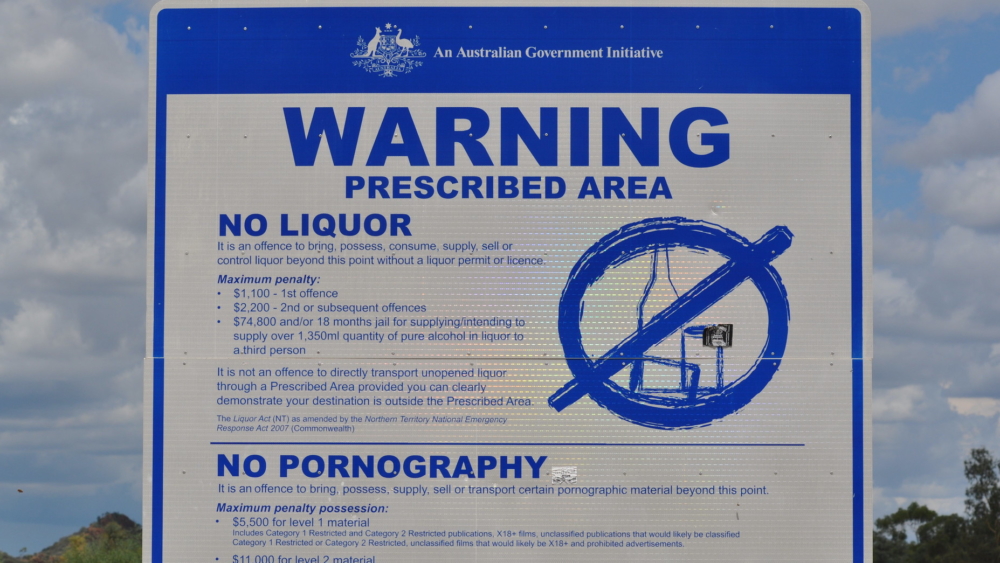

Men in military uniforms were sent in to round up communities, informing them of sweeping changes to their lives. Communities were told it was for their own good, given the threat they caused to themselves and others around them. Signs were erected in front of towns with the words “Warning – Prescribed Area”.

Later it was revealed that the “youth worker” interviewed by the ABC was a parliamentary staff member on Brough’s team. But it was too late for the Aboriginal families who had fled in fear as troops moved in.

I’m ashamed to admit it now but, before working in the NT, I subconsciously picked up the notion that Australia’s Indigenous peoples had somehow brought the inequality they experienced upon themselves.

Even worse, that with a bit of ‘guidance’ from my white self, their lives could easily be turned around.

All over Australia, Indigenous people have their own unique story of survival. A few communities away from Warlpiri country, in Alyawarre land, I visit Ampilatwatja. Their septic tanks and drains had been left without maintenance from local council. One day, they awoke to ankle-deep sewage in their houses. They had no choice but to abandon their homes.

When the local council finally did address the problem, their solution was to dump three tonnes of raw sewage just a few kilometres away. The stench, when I visited many months later, was still unbearable. When a local Indigenous man employed by the council, spoke out on the issue, he was sacked.

The men and women I met were never motivated by personal material gain.

It’s easy to see how Indigenous Australians so often feel despondent and in despair. When basic services can’t even be met, people are made to feel like outcasts on land their ancestors have held for thousands of years. If this had occurred anywhere else in Australia, it would be proclaimed a national disgrace. It seems a sad reality, that when we hear or read stories of injustice to our First Nations People, it is easier to brush it aside. We need to change this. These abhorrent stories should make us feel uncomfortable.

As Christians, we should prayerfully consider how we can respond, in light of Jesus’ message of love.

Working with Warlpiri communities amid the turbulence of The Intervention, I was nonetheless struck by the community’s resilience.

It would be easy to list the number of social issues that affect the day to day lives of community members. However, the things I have remembered most and the lessons I learned flow from the values which First Nations Peoples placed upon improving the lives of their families and communities.

Despite having so little, the men and women I met were never motivated by personal material gain. Their motivation was to improve their whole community, so the quality of lives could improve for their children. And if it wasn’t their children, it was their parents, siblings and wider families. Their ‘kinship’ system was a specially crafted network of how they managed relationships with each other, based on respect and love.

And despite their painful history, they have fought hard to keep their language alive and culture strong – even in the face of continued challenges, such as bilingual projects at schools being scrapped. They have also fought hard to maintain their connection to land, with song, story and dance as the cornerstone, bound together by language.

Looking back at the devastation caused by The Intervention and its continued impact, I cannot help but put myself in the shoes of those most affected.

The Northern Beaches, where I grew up, have the highest rates of drink driving in New South Wales. What if, given this, and the recent Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse – which uncovered how unsafe some churches have been for children – the government decided to dispatch troops to all the Northern Beaches churches one Sunday? Then, they erected fences and put up signs warning others to stay away.

What if we turned up to church one day to a government lecture on the dangers we were causing to society and news that sweeping changes were being introduced to control us?

The thought is, of course, incomprehensible. We can only conceive of this happening in far-away countries ruled by military juntas. Yet this is what has happened in our own country to our First Nations Peoples. This is not some far-off nightmare that is inconceivable for Indigenous Australians but an everyday reality.

I once thought the injustices experienced by Indigenous Australian were a thing of the past. But the harsh reality is they still exist today.

Lately, I have been thinking more often about this mistreatment, due to various media stories gaining prominence. Earlier this year, it was exposed that a hotel chain in Alice Springs was segregating Indigenous guests to dilapidated hotel rooms, while non-Indigenous people were given better rooms. I wasn’t shocked.

Anyone who was Aboriginal was told they needed to use the filthy and discarded toilets out front.

Years ago, as a new NT worker, I had discovered that on the road to Yuendumu, there was only one road house to fill up at for the long journey ahead. It was called Tilmouth Well and on the doors to the restaurant and toilets there was a sign that read ‘House Guests Only’.

I then learned you were a “house guest” if you were white. Anyone who was Aboriginal was told they needed to use the filthy and discarded toilets out front. They were refused entry at the restaurant. This was less than one decade ago.

It’s easy to dismiss the ideas of racial segregation as abhorrent systems of the past in other countries – apartheid in South Africa, or post-slavery America. But how should we respond when we learn this still happens today in Australia? Whether it’s the subtlety of a “house guest” sign, or being consigned to a dilapidated hotel room, this is the lived experience of Indigenous Australians, and they must carry the heavy weight of this discrimination everyday.

A recent ABC 7:30 Report interviewed people visiting Uluru, located in the stunning land of the Anangu people. My wife and I have visited the sacred site and found the national park to be a remarkable collaboration between Anangu and government, with a cultural centre that proudly explains its importance to Anangu people and how non-Indigenous people can respect the sacred site.

One of those ways is to honour the request of the local people for visitors not to climb the rock. With climbing to close today (October 26), recent reports have shown a sudden influx in numbers to the national park in a last-ditch attempt to climb it.

But it’s not all bad news. While the numbers of visitors to Uluru are increasing, Parks Australia reported that 86 per cent of people choose not to climb – a stark contrast to decades ago when most visitors did so.

For the first time, Australia’s Indigenous Affairs Minister is actually Indigenous. Ken Wyatt is a child of the ‘Stolen Generations’ and has called for a referendum on constitutional recognition within the next three years.

And in Yuendumu, the success story of the Mt Theo program is a remarkable one. Founded in 1994 when half the youth were petrol sniffing, the program brought together non-Indigenous Australians working in true consultation and collaboration with elders. Eight years later, petrol sniffing had been eradicated and local youths were becoming community leaders and youth workers. It is a legacy that continues today.

How can we expect to thrive as a nation when we its original inhabitants still suffer so much?

Whenever I think of my Indigenous brothers and sisters, I’m constantly reminded of Matthew 7:24 – the Parable of the Wise and the Foolish Builders. As Jesus concludes his famous ‘Sermon on the Mount’, having laid out his moral foundations, he notes that they are like a rock. I have tried to thoughtfully consider how this applies throughout my life, whether it’s family, relationships or work.

But when I think about the post-colonial ‘birth’ of this nation and the ongoing mistreatment of Aboriginal Australians, it seems to me that the foundations of this country are built on sand (like the Foolish Builder mentioned by Jesus).

How can we expect to thrive as a nation when we its original inhabitants still suffer so much?

For our country to change its foundations to rock, we need true reconciliation with Indigenous people.

If as a nation we are to survive as the “rains come, streams rise and winds blow and beat against us”, we need to be heeding Jesus words and lived message of caring for those who are most needy.

People often comment that the issues facing Indigenous Australians are complex. This may be true, but the solutions don’t have to be. There’s nothing complex about Jesus’ message of love – showing true respect, dignity and equality when dealing with First Australians.

Many believe this should start with constitutional recognition, while critics will argue that it is mere symbolism without action.

For me, the two need not be mutually exclusive. We can and should show respect, not only through symbolic gestures but also through our actions. This is when true reconciliation will occur.

I no longer dream of Africa and working for the United Nations. I have learned that working out what it means to be white on Indigenous land is challenging enough.