Love your everyday enemy every day

From co-workers to inmates, how can we respond to opposition?

I don’t think there’s any more difficult part of Christian discipleship than finding what it means to love your enemies, and then actually doing it.

We cannot sidestep this call. It’s what Jesus clearly teaches. It’s what Jesus himself models.

When we think of love for enemies, we normally imagine scenes less ordinary.

And yet … it is so darned hard. Take these real life (disguised) situations:

Phoebe is in the middle of a bitter divorce. Her husband has tried to prove that she is mentally unstable and is busy hiding their assets. There is a real possibility that she will be unable to see her kids. In fact, her husband’s new girlfriend is turning the kids against her. He’s also been openly mocking her faith in front of them and painting her as a religious fanatic.

John has recently discovered the reason why his career has stalled. A work colleague has been undermining him to management and even to clients. Now that he knows, John has had to start seeing a psychologist. He’s been moody and distracted at home, and his wife thinks their marriage is in trouble.

The strata committee at Frances’ block of units is locked in a bitter dispute about renovations. There’s a group of residents who are trying to force her to leave. It’s become deeply unpleasant to encounter her neighbours in the lobby – there are under-the-breath comments about her being a stingy old lady. Threatening anonymous letters have been slipped under her door.

What might it mean for Phoebe, John, and Frances to practise enemy love?

When we think of love for enemies, we normally imagine scenes less ordinary. And yet, here, in the midst of everyday life, we find enemies – not just people we dislike, but people who wish to do us harm.

What might it mean … to practise enemy love?

When Jesus taught us: “love your enemies” he had in mind specifically the enemies that we gain through being his disciples. There are those who will be determined to destroy the people of God. There are those who encounter Christ-like behaviour as a deep offence to the way things should be, and want it eradicated from the earth.

But that is not our only experience of enmity. As the disciples of Christ, we are called on to love our enemies – whether they are specifically attacking us for our faith or not.

When we are sitting amid an experience of being hated, everything within us cries out for vengeance. When we are under assault and our livelihood and even our identity are under attack, what are we to do? It not only seems impossible to think of loving our neighbour, it actually seems unnatural. Our enemies wish to conquer and destroy us, to leave us vanquished. To survive, we should return their enmity. Shouldn’t we?

When Jesus teaches his disciples to love their enemies, however, he is not giving them a cute or romantic piece of advice.

Love your enemies … because that is exactly what God does.

Love for enemies is in the first place based in the character of God. Jesus says: Love your enemies … so that you may be children of your Father in heaven; for he makes his sun to rise on the evil and on the good … be perfect therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect. [Matthew 5:44-48]

Love your enemies, in other words, because that is exactly what God does. He showers his providential care upon those who love him and upon those who ignore and even hate him. They receive his kindness, whether they regard him or not. A special sun does not shine on those who love God, leaving all the God-haters in deep darkness. It shines alike on all.

Jesus might have gone on to speak of God’s redemptive love, too. In Romans 5, Paul speaks of God’s particular love for us in that “while we were still his enemies” Christ died for the ungodly. The death of Jesus was the ultimate act of enemy love. He offered himself not while we were in the midst of turning to him, or because we had somehow shown that we had a spark of love for him.

On the contrary. That’s the love of the pagans, says Jesus, to love those who love you. Who doesn’t?

And so, here’s the central thing about enemy love. We love our enemies because as enemies we were loved.

I think we get confused because we forget what love actually means.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer said that the Christian disciple’s behaviour “must be determined not by the way others treat him, but by the treatment he himself receives from Jesus.” And how have we been treated? We have been loved even in our hostility and rebellion against him. We’ve received grace and mercy, even as we were ungrateful and unkind.

That is who the disciples of Christ are. They call God their Father, undeservingly. They know the sweet taste of forgiveness. Like the prodigal Son, they have come home to a Father they once wished was dead to find his welcoming embrace.

Thus, we do not look at our enemies and calculate how they’ve hurt us and how we can return the hurt in kind. We remember Christ – and that is the basis for how we approach our enemy.

But does that mean I have to let my enemy win? Do I lay down passively and allow their hatred free rein?

I think we get confused because we forget what love actually means. We are so obsessed with allowing people their individual choices that we think that loving someone means letting them have what they want. Not at all. Bonhoeffer says: “The will of God … is that men should defeat their enemies by loving them”.

Love says “no” as well as “yes.”

To love your enemy is not to concede everything to them. Jesus did not do that.

If love is truly wanting the good of the other person, then loving your enemy is not letting them revel in their dishonesty or hatred. It’s not loving them to allow them to keep on doing evil, to you or anyone else. Love says “no” as well as “yes.” It is firm but kind. It makes space for a person to repent, while at the same time letting them know that there is something of which to repent.

We do not condone the enemy’s evil by loving them. That is our great fear. We imagine that if we do not return hatred towards hatred, if we do not wish to destroy those who wish to destroy us, then we are even in collusion with our destroyer.

Forgiveness is often misunderstood in this way. If we forgive, are we not allowing justice itself to collapse? Not at all. True forgiveness – one example of loving one’s enemy – speaks honestly. It actually judges and condemns evil, or evil is not truly forgiven and the enemy not truly loved.

In this way, the enemy is actually conquered. As disciples of Christ, we show ourselves protected by the love of God for us. We experience hatred, but we need not fear its destructive power. We have a blessed freedom that the enemy does not know.

Our enemies expect us to cower in fear, or to retaliate in kind. But we are the disciples of a resurrected Lord! We choose neither. We speak the truth and we hope in Christ.

Jesus doesn’t give us a step-by-step programme to enemy-love.

So what could this mean for our experiences of having enemies?

First of all, I think it is vital that we understand we are not talking about those against whom we feel enmity. Perhaps we are the enemy of others. It could be that the hatred has begun in our hearts, and not in theirs. Let it not be so!

But what about those who are destroying us? Our abusers? Our implacable opponents? The workplace bullies who have caused us mental health problems? We love them not by ignoring their evil behaviour but because of Christ’s love for us.

But how? There’s no pamphlet of instructions on this. Jesus doesn’t give us a step-by-step programme to enemy-love. I think we simply have to ask in each situation: What does it mean to love my enemy here? What can I do to serve them, so that they are vanquished by the love of God which is in me? How that works is up to you. But if you know you are safe in God, you can act with daring and surprise. Change the game.

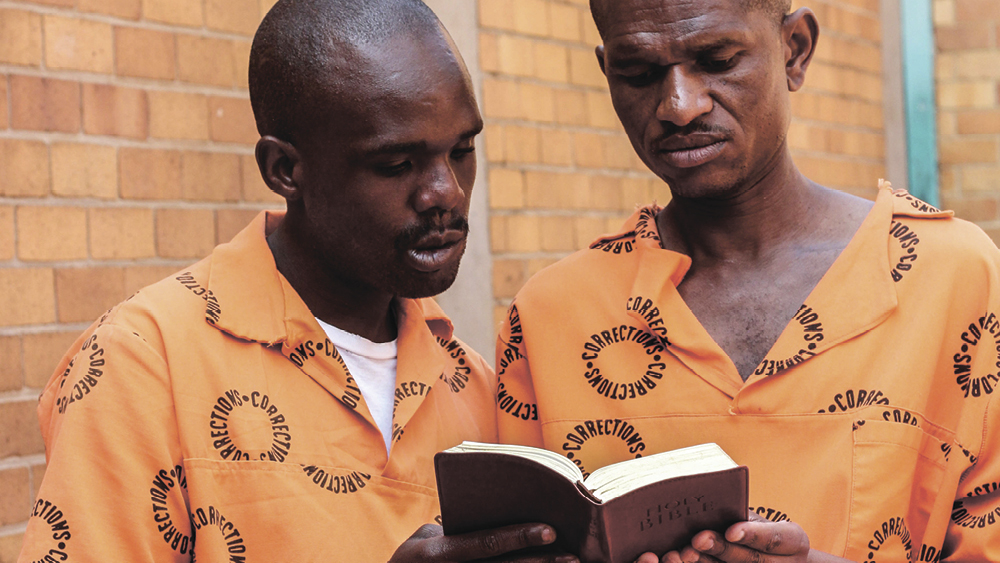

A friend of mine who works in prison chaplaincy recently told me a story. The inmate “Ben”, who ran the Christian group in one of the wings of the prison, was also the chief sweeper – a position of responsibility within the wing. The daily prayer and Bible group in the wing had grown to about 40 per cent of the inmates. Ben made a rule if you got into a fight you couldn’t come to group for a week.

But if you know you are safe in God, you can act with daring and surprise.

But another group of inmates wanted to take control. So they started petty thieving from the other inmates. Now, usually, if that happens, the group in charge puts the thieves in hospital, or their authority is gone.

So what was Ben to do? Do nothing, and seem weak? Or organise violent retaliation, when he’d been speaking against it as a Christian?

My friend said: “I had no idea how to advise him to act Christianly in this situation. But he figured it out. One morning he stood up with the other Christian leaders and said, ‘there has been thieving, and I will not have it. Here are ten fellas who all get the full buy-up every week. If anyone needs something, anything, we will give it to you, no questions asked. But you will not steal anymore.’ It was startling. He won the influence in the wing, even won a bunch of the other guys over. They handed the thieves over and they were removed with no violence.”

That’s what love for enemy means. And that’s what it can do.

Michael Jensen is the rector of St Mark’s Anglican Church in Darling Point, Sydney, and the author of several books.