I’ve had the privilege just recently of a week of intensive study at one of the world’s great universities. Now I have to remember what I learnt. There’s no chance that I’ll remember everything; and it’s a little unpredictable whether I’ll remember the most important things, or simply the entertaining parts (such as when the lecturer broke into song).

That’s the truth: we forget most things.

If I’m going to make some of that learning stick, I’ll have to practise remembering. I’ll do it by rewriting notes, by telling other people about it (annoyingly) and by periodically rehearsing the way I first learnt it (usually by bringing to mind the way the lecturer spoke, or visualising what she wrote on the board). These techniques have to be used to overcome the natural human tendency to forget most things.

Because that’s the truth: we forget most things. We have to, or our brains wouldn’t cope. Our mental filing cabinet would be chock-full to that point where the drawers won’t close properly and we are catching our metaphorical sleeves on their sharp corners. We filter and distil our experiences so we can move on to the next ones.

There’s also collective memory, and collective forgetfulness. Cultures remember all sorts of parts of their history, and forget other parts. They mark some events with special days, festivals, name plaques and poems. Other parts just drift away, unnoticed until it is as if they never happened. They did happen, of course, and they left their mark on things, but because no one remembers, we are not able to explain how things got to be the way they are now.

This is why I’m supportive of the study of “marginal” cultures, because it seeks to stymie the forgetfulness, to cauterise the powerful forces of collective reminiscence which favour some cultures over others. This is why the rise of historical study of women, conquered people groups, minority cultures and the like is not mere political correctness but often historical correction. It’s trying to remember things more, and more comprehensively, before important truths are completely lost.

The recent focus on the indigenous leader, William Cooper, is a potent example. We celebrate NAIDOC week now in July, but very few of us know its origins in this great justice campaigner. Cooper beseeched the nation’s churches to come together in prayer that the word of Christ would ring out through this country for both indigene and settler alike.

That was Cooper’s National Aborigines Day, which began 80 years ago in 1938 but slowly morphed into NAIDOC Week (and away from Australia Day into July), until its origins were forgotten. Well, nearly forgotten. Judging by the buzz last month during NAIDOC Week, it seems to be coming back to life.

Christian faith depends on remembering well.

The rise of DNA technologies has helped us to face the reality of the past. Just because something has been lost to memory doesn’t mean it is unimportant or, in our worst fantasies, didn’t happen. We just manage to let memories lie dormant if it is too inconvenient for us otherwise. But DNA won’t let us forget. Archaeology won’t let us forget. Literature won’t let us forget. But we have to pay attention, and practise remembering.

Christian faith depends on remembering well. We have to remember who we are (God’s creatures). We have to remember what we were (sinners in God’s eyes). And we have to remember why we have hope (Jesus Christ is Lord). How well we track in our journey through life comes down to how well we remember these things.

In the end, someone has to be able to do the remembering perfectly. That person is God himself, who can number the hairs on our heads, whose capacity to remember is unlimited, and who feels no need to leave anything out. He has the robustness to cope with reality. He’s got the whole world in his hands, and in his mental filing cabinet.

He can without effort remember everyone and everything from the beginning of his creation, in order that he can renew it completely when the time is right. None of those memories will go to waste.

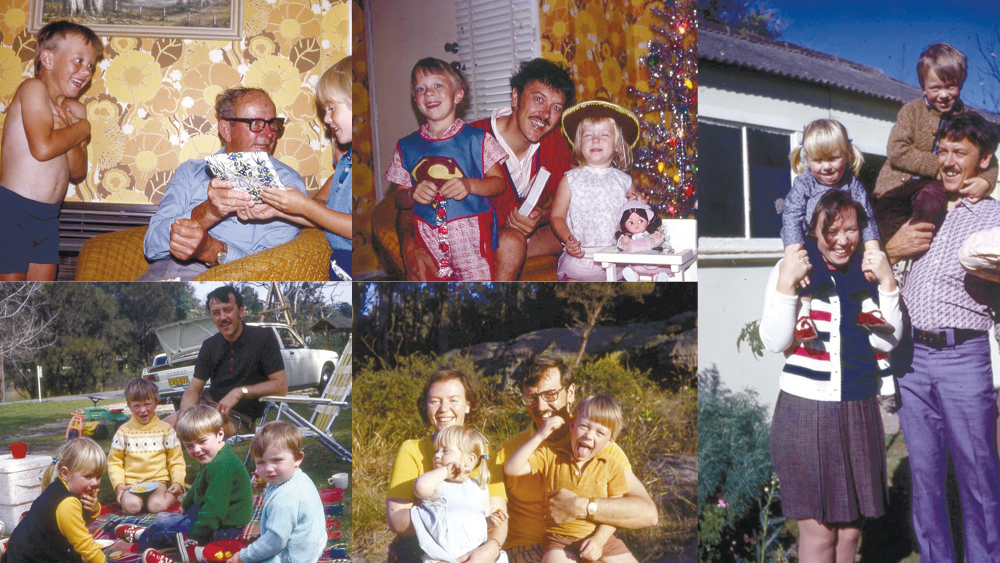

In memory of my father, James Sydney Clarke (1942-2018). He was a lovely Dad.

Greg Clarke is CEO of Bible Society Australia.