Have we lost the art of disagreeing well? Is it recoverable? Laments over the incivility of our public square seem to appear almost daily now, and the genre is not an optimistic one.

Take the sudden furore back in March when Bible Society Australia (BSA), as part of a campaign associated with its 200th birthday, released a video featuring two Liberal politicians debating same-sex marriage. Its message was that civil discussion of heavy issues can be part of what it means to “live light” (the tagline of BSA).

Same-sex marriage advocates denounced the video as (at best) disrespectful. Everyone from The Guardian to the Tele, from The Drum to Charlie Pickering, weighed in. In the immortal words of Ron Burgundy: “Boy, that escalated quickly. I mean, that really got out of hand fast.”

In a culture of offence, suspicion is default and grace is in short supply.

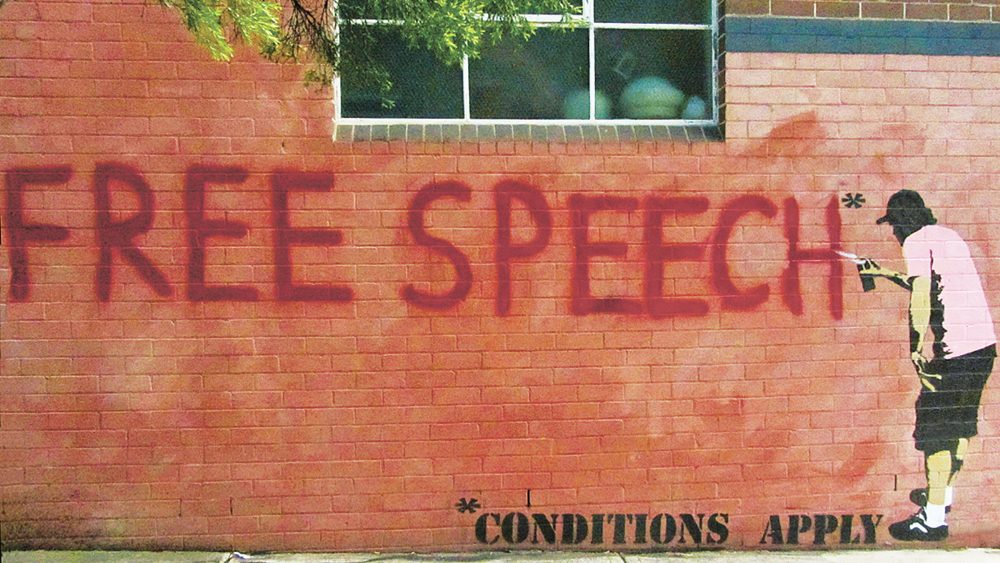

There’s a lot to say here about free speech, outrage, conscience, social media, how to change minds and so on and so forth. But, now that the dust has settled, a more pertinent question might be: how should Christian people specifically respond to these kinds of meltdowns?

I’m not at all sure I know. But here are a few thoughts that should hardly be controversial for Christians (famous last words!)

1. Choosing grace

In a culture of offence, suspicion is default and grace is in short supply. And grace is a resource that followers of Christ need never run out of; it’s the thing we should always have to offer a conversation, issue, or relationship. “But he gives us more grace” (James 4:6)!

It’s tempting, especially on social media, to “pounce” on everything we could possibly find anything to quibble with. There’s always someone or something to criticise, on any side of any issue. But against the prevailing Twitter-tides, we should seek to give others the benefit of the doubt; to listen well, and be awake to people’s hurts and fears; to believe their motivations are good, however strongly we might disagree with their choices or conclusions; and to want the best for them. “Bless those who curse you, pray for those who ill-treat you” (Luke 6:28). How can we speak and enact blessing for people we disagree with?

2. Taking risks

For the record, I really enjoyed the Bible Society’s “Keeping it light” video. But maybe you hated it. Maybe you thought it naive or tone-deaf or too male or too white or ill-judged in some other way. Maybe you jumped into the Facebook feeding frenzy without even watching it in the first place!

If it’s totally “safe,” it’s probably not got much to do with Jesus or the Bible.

Maybe it’s not how you would have done it. But historically, Christians try lots of different ways of getting their message across, with differing (and hard to predict) rates of success. Though some options are certainly wiser than others, and we should exercise caution and gentleness, there’s always some level of risk involved. If it’s totally “safe,” it’s probably not got much to do with Jesus or the Bible.

Dorothy Sayers wrote a half-century ago about pastors that “if [they] are to refrain from saying anything that might ever, by any possibility, be misunderstood by anybody, they will end – as in fact many of them do – by never saying anything worth hearing.”

We have different methods and we’ll get it wrong sometimes. But let’s support one another, insofar as we possibly can: “To their own master, servants stand or fall. And they will stand, for the Lord is able to make them stand” (Romans 14:4).

3. Losing well

The natural human response is to meet hostility with hostility, outrage with outrage. It’s a predictable process, one we’re all too familiar with in the current climate. How can Christians break that cycle, rather than perpetuating it? Well, we look to Jesus, who said “love your enemies” and submitted to indignity, torture and death at the hands of his.

Christians should be bold and courageous – but never jerks, let alone sore losers. We don’t meet a boycott with a counter-boycott, or abuse with abuse.

(Of course, it’s also worth reminding ourselves that these local kerfuffles are a completely different ball game to the serious persecution faced by Christians around the world on a daily basis.)

Christians should be bold and courageous – but never jerks, let alone sore losers. We don’t meet a boycott with a counter-boycott, or abuse with abuse.

We keep articulating a case for religious freedom and freedom of speech, but we don’t mobilise for battle.

As John Dickson writes in an article on the “art of losing well”: “No group in society should be better losers, more cheerful sufferers, than followers of the crucified Lord.”

4. Living light?

The law of unintended consequences applies to everyone. But Christians should be especially aware that we do not control outcomes – that whatever our efforts and intentions, God alone is sovereign over what happens, above all over the ways his word will take root and grow and achieve the purpose for which he sent it.

We don’t live and die by the news cycle; we don’t need to participate in the culture of confected outrage.

This means we can relax! We don’t live and die by the news cycle; we don’t need to participate in the culture of confected outrage. We can afford to be generous, humble, and unruffled, because we know the One who directs the course of people’s hearts like streams of water in his hand (Proverbs 21:1). The Lord of Hosts is not thrown by the fluctuations of public opinion – and nor should we be.

Natasha Moore is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Public Christianity.