Street benches are better than church buildings

If you want to reach the inner city, ‘stop going to so many church activities’, says Karina Kreminski

Where Karina Kreminski lives, in the gritty but rapidly gentrifying urban village of Surry Hills in Sydney, most people don’t like the church.

“I know,” she says sadly, when her friends tell her their tales of how they have been hurt by the church. Or “I don’t know,” she says, shaking her head.

But when Karina, a lecturer in missional studies at Sydney’s Morling College, takes the opportunity to tell her friends and neighbours about Jesus, she finds they have much more positive responses.

Karina Kreminski in a cafe on Crown Street, Surry Hills, Sydney

“One woman that I connect with, who I really love, is transgender and she is deeply, deeply spiritual – she’s just really interested in spiritual things – so we always talk about Jesus,” Karina tells me as we sit in a hip café on Crown Street.

When Karina mentioned to her transgender friend that Jesus hung out with all sorts of people who were on the fringes of society, the friend exclaimed, “If Jesus were alive today he would hang out with people like me.”

The remark was a moment of epiphany for Karina.

“First of all, there was a grief because I thought that she sees herself as an outcast,” she explains.

“But then also it was such an overwhelming ‘yes’ to me when she said that. So at the same time, she feels marginalised and rejected but is drawn to Jesus, and that was really sweet for me … it was a very emotional reaction.”

For Karina, the experience reinforced her belief that Christians have to change their ideas of holiness from living in a Christian bubble untouched by the world to connecting with his mission in the local neighbourhood.

“If you just embody that beauty and you present Jesus as he is, deeply attractive, people will be drawn to him as they were when he walked this earth. People desperately wanted to be with him – I mean, the most marginalised people today are running away from church. It’s just a very strange, strange, strange situation we’re in in the church today, in particular Sydney,” she says.

“And he was holy – holiness is like ‘keep away’ these days – we’ve got to change that. We talk about being missionaries in other parts of the world – we need more ‘missionaries’ in secular Sydney.

“If you just embody that beauty and you present Jesus as he is, deeply attractive, people will be drawn to him.” – Karina Kreminski

“We need that because who are the people that are furthest from the kingdom at the moment? It’s the intellectuals, the artists, the secular people – they’re the ones that see the church and never want to go anywhere near it. They would never think to wake up in the morning on a Sunday: ‘Oh, I might go and check out the church down the road that has this sign that says “marriage course” or “marriage sermon series” this week.’ Nobody wakes up and thinks that in Sydney any more.”

About seven months ago, Karina teamed up with three of her creative neighbours – all non-Christians – to create a website, Surry Hills and Valleys, that tells the stories of local people whose suburb is leaving its rough, working-class history behind and becoming a cool place to shop, drink and dine.

“I started thinking there’s so much change happening in Surry Hills – some people have been here for 30 or 40 years, so they’ve seen all the changes. I’ve already seen so much change and I’m already grieving and I’ve only been living here two years.”

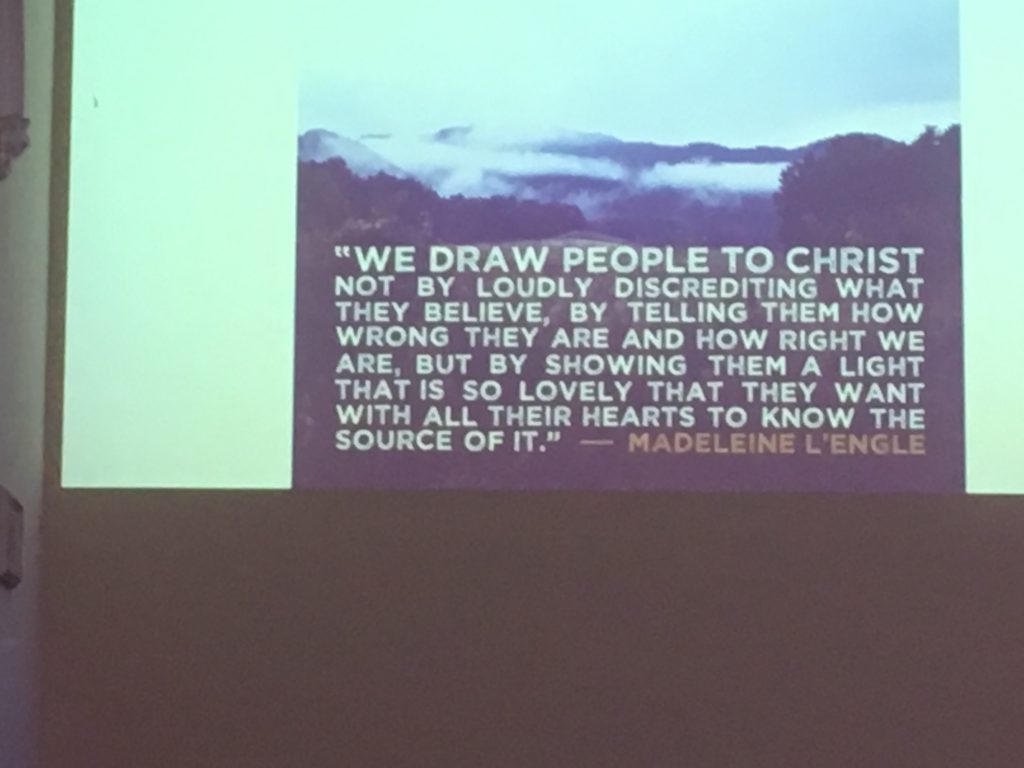

A quote that Karina Kreminski finds inspiring

She finds it relatively easy to find people to interview in the village-y atmosphere of Surry Hills, where people often talk to each other in parks and cafes.

“It’s just random. I was sitting on a park bench a couple of months ago and a lady with a dog just came over to me and I noticed the dog was limping. I said ‘your dog is limping’ and we just started a conversation and we did become friends. I’ve interviewed her, she’s very strong here in the gay community, so [the local magazine] did a feature on her last time.”

Karina hopes that eventually she will be able to start up a Bible study with some of her new friends.

“So my idea is we read a passage of a gospel each week and we ask ‘what do you find strange about the passage? What is it calling you to do? Who is Jesus in this passage? What is he asking you to do?’ Just that. And then just have a meal and, if they’re open to it, pray for one another and that’s church. So I’m hoping to move towards that, but I think that might happen in a year.”

While Karina recognises her own privilege in being able to buy a box-like unit in inner-city Surry Hills, she believes it is important to be aware of the people around her who aren’t privileged.

“Don’t necessarily help them because I think that can sometimes be a form of power over them, but just be with them. For me, friendship is a really important concept. I wish more people would write about the theology of friendship because to be friends with somebody who is very different to you is radical – it can really change you.”

“Someone said ‘if we find some people smell bad, retrain your nose.’ – Karina Kreminski

She agrees that it can be a struggle to be friends with a homeless man who smells of body odour.

“Someone said ‘if we find some people smell bad, retrain your nose.’ You know what? There’s a lot of truth in that because there are people who, physically, it’s difficult to be around; but just think, ‘this is part of who this person is because of their circumstance, but they’re human beings, God loves them and what they really need is companionship.’

“Governments all over the world are discovering now that loneliness is the issue to tackle so what should the church do? Give out blankets and food and shelter? Yes, but also be friends with them and that’s harder because you have to invite them into your home, and for many Christians my home is my castle, this is where I look after my family, I invite other Christians in there – safe people – so real hospitality is subversive.”

When asked how Christians should find non-Christians to make friends with she advises: “Stop going to so many church activities!”

“But what does it look like to practise spirituality in a busy, urban space where you’re on the go all the time?” – Karina Kreminski

“We talk a lot about a surrendered, sacrificial life, and we can be fooled into thinking that sacrifice and surrender means putting your name on the morning tea roster on a Sunday morning because you have to get up early. The sacrifice is actually hanging out with that transgender woman who lives down the road,” she says.

Karina has put a lot of these ideas into a new book, Urban Spirituality: Embodying God’s Mission in the Neighbourhood (published by Urban Loft Publishers next month), which is intended to help churches to be outward oriented rather than focused on themselves.

“When we think about spirituality, often it’s about withdrawing, retreating: we close our eyes, we go into our rooms, we think about living in the mountains, forging the hills and the valleys. But what does it look like to practise spirituality in a busy, urban space where you’re on the go all the time? Where there are significant issues of homelessness and mental illness, and mixing with people who are very different to you – the gay community, others who are struggling with their sexuality? What does a spirituality look like that’s fleshed out and grounded and engaged with the world rather than being mystical, other-worldly?”