Ossie Cruse’s battle with the bottle started at age 12, a year after he was forced out of school, and by the time he was 15 he was well on the road to alcoholism.

The highly respected Aboriginal Christian belongs to a generation of battle-hardened political warriors who fought through the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s for Aboriginal rights. The ABC called him one of Australia’s “last great Aboriginal patriarchs” in an Australian Story programme about him last year.

Yet, in an interview with Eternity, he is frank about his hard-drinking past and the miracle that transformed him overnight.

After marrying Beryl at age 18 he continued drinking heavily and “in those early stages of our marriage I took her through hell because of the way I reacted to alcohol.”

“In 1962, I was pretty well spaced out. I was an alcoholic,” he tells Eternity.

Ossie knew that his life was a mess, so in 1962, at the age of 29, he went to a meeting in Sydney’s La Perouse, where he was living, to hear an Aboriginal evangelist called David Kirk.

“I needed to change ’cos I made many resolutions never to drink again and I’d still go back on it, and so I went along to this meeting,” he recalls.

“David Kirk was a really incredible man – he could play music and sing – and listening to him preach the gospel is when I come under conviction that my life needed to be changed radically by the Lord Jesus and I came to know him as my Lord and Saviour at that convention.

“My wife came the night after because she was an addicted gambler – she loved gambling, … and both of us changed so radically – it was just incredible the way things turned out for us – and the children. We already had three children.”

Ossie explains that what took possession of his life that night was the understanding that the love of God is real – and the Prince of Peace transformed everything.

“When I became a Christian in 1962, everything changed, radically changed. I never wanted to drink again, I never had withdrawals, I never even had to go to any sort of counselling, but my life just so radically changed. One minute you’re lacing your sentences with four-letter words – swearing – and, like, the next day when I put my life in the hands of the Lord, I just couldn’t stand to hear people swearing, let alone ever wanting to drink again.

“So to me it was a miracle, a miracle that saved me all the way even today. I never, ever desire to go back into that old way of life.”

In 1968, as an enthusiastic lay worker in the church, Ossie was involved in the early discussions that led to the founding of the Aboriginal Evangelical Fellowship (AEF) of Australia in Port Augusta in 1970. He became one of its 70 foundation members.

A young Ossie Cruise

Speaking to Eternity at the AEF National Convention in Port Augusta in January, he recalled the difficulties of those early days.

“Back in the early days, you were always conscious of the fact that we were still living under a colonial regime and Aboriginal people were never expected to be anything other than just servants or, you know, never having really the same zeal as the Anglo-European to be involved in things of high profile,” he says.

“And I think that’s where the problems began because we had Aboriginal men that were ready for service but never really fitting in – they were always, most times they were assistant workers and the fellows started to get a bit impatient and say, ‘Well, no, we are ready for leadership.’”

“We weren’t going to create another denomination but a fellowship that was transcending all the mainline evangelical denominations.” — Ossie Cruse

The problem was the mode of thinking in the mainstream denominations that required a senior pastor to have a university degree, he says.

“But we ourselves believed, no, all you need to do is to know the gospel, know your Bible and know how to speak to people about that, and that was all that we needed as a credential for us to be leaders or pastors … so AEF was giving Aboriginal people the opportunity to share the ministry in their own communities in a culturally appropriate way.

“We saw that our mission to Aboriginal people was more or less on their level, but we would never reach this credential of being a reverend as such for that particular ministry.

“And so, there were conflicting things that came in with all denominations that way. But we saw that we weren’t going to create another denomination but a fellowship that was transcending all the mainline evangelical denominations.”

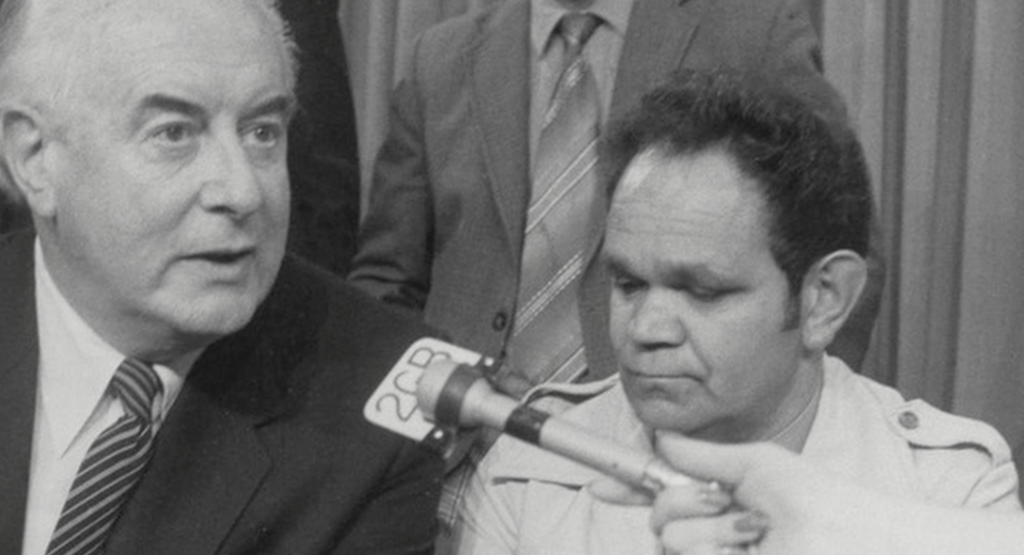

In 1982, Ossie travelled with former prime minister Gough Whitlam to post-colonial African countries to drum up support for a treaty with Aboriginal people in Australia. He took his advocacy all the way to the UN and became a member of the World Council of Indigenous Peoples, paving the way for the UN Declaration of Rights for Indigenous Peoples.

Ossie Cruse (right) with then prime minister Gough Whitlam.

In the Australian Story programme about Ossie, Aboriginal MP Linda Burney says that, as a member of Federal Parliament, the lesson she has taken from Uncle Ossie is “quiet leadership”.

“It is that understanding that persuasion is not about thumping the table and yelling at people. Persuasion is often long and arduous, quiet and persistent,” she said.

For his part, Ossie believes that if God had not intervened in the lives of Aboriginal leaders such as himself in the 1960s, there would have been bloodshed and havoc in this country as high-profile Aboriginal activists “would’ve very easily taken the road of vengeance”.

“But instead we chose the Scriptures. Say ‘love your enemies and do good unto those that would despitefully use you’, and so the AEF was born in that mode,” he says.

“To preach the gospel to all Australians, particularly emphasising Aboriginal people, and when we formed it we never intended that it would be singled out as just an Aboriginal body. The greater number of our members are non-Aboriginal people – that’s how we deal with this colonial stuff.”

“I don’t want to say ‘take all these cars and get out of this country, take everything with you.’ That’s not an attitude. That’s a ridiculous attitude.”

Ossie is a member of an organisation called the Acts of Recognition which has been working for a recognition of the wrong that was done to Aboriginal people when James Cook declared the country uninhabited – “terra nullius” – and to establish a treaty that will bring peace between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people.

“And I really believe it can happen. The churches in the main are getting behind it,” he says.

Ossie, whose focus had always been more on civil rights than land rights, insists a treaty would not be about taking the land back but about living as one nation.

“We have no intention, or I would have no intention, of looking at this as a monetary thing,” he says.

Ever the peace-maker, he hopes to allay such fears, which he says derive from a lack of understanding that “we want to live as one people”.

“I don’t want to say ‘take all these cars and get out of this country, take everything with you.’ That’s not an attitude. That’s a ridiculous attitude.”

“I think we’re sane enough now and developed enough now to want peace in this country at all costs.”

He believes churches of all denominations need to work together to teach black and white children together, as Ossie is doing in Eden on the NSW south coast, where he lives now.

“It’s the way we should be working as people, the custodians of this land together, and that’s where I think the fears of people need to be laid to one side. I don’t think they should ever really fear. That sort of fear is what brings about revolutions and all sorts of other things. I think we’re sane enough now and developed enough now to want peace in this country at all costs.

“We must administer justice to all people – white and black must have justice – and that’s what we’d be working towards – truth and justice for everybody.”

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?