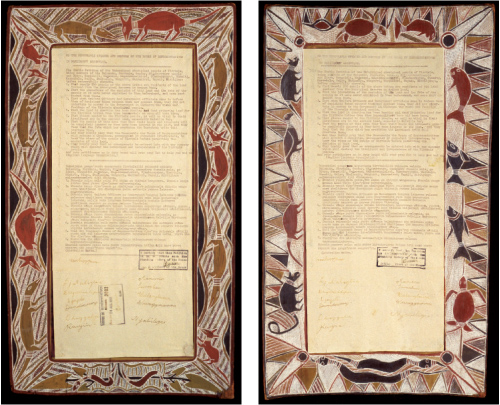

At first it seems out of place among the oil paintings and elaborately printed documents displayed in Canberra’s Parliament house. But two sheets of bark, with aboriginal paintings around a typewritten sheet of paper are some of the most important documents on display.

The Yirrkala Bark Petition is the theme for this year’s NAIDOC week, which celebrates indigenous culture and history. Fifty years ago, the aborigines of Yirrkala sent a petition, placed on a painted sheet of bark to the Commonwealth Parliament. It not only was a key document in the land rights but also launched the Australian Church into the debate.

In One Blood, a magisterial warts-and-all history of Christians encounter with Aborigines, John Harris, sees Yirrkala and the bark petition as a turning point. Depending on your point of view Yirrkala is the story of a brave missionary taking the side of an oppressed people—or of the church betraying the vulnerable.

John Harris is Bible Society Australia’s consultant and éminence grise. And this article summarises the story Harris tells in One Blood.

Yirrkala in Eastern Arnhem Land was a Methodist mission. Unfortunately as mineral exploration took place in the NT, it was found to be the site of a massive bauxite deposit.

In 1957 the Methodist Mission’s lease ran out. “The Commonwealth did not see fit to renew it, changing it to a ‘Special Purpose Lease’, which could be taken away for other purposes such as mining” reports Harris. “In other words the legal ground was being prepared for mining to begin. It is interesting to compare the reluctance of the government to renew mission leases with ease with which the same government could grant mining leases of up to 100 years.”

The next year the Methodist Mission board and the NT administration made a formal agreement that the reserve land could be transferred for mining. “Although it was in no way a secret agreement, it was not made particularly public”, Harris diplomatically explains. “… No aboriginal people were consulted, nor was any mention made of the arrangement at the Methodist synod.” Cecil Gribble, General secretary of the Methodist Overseas Mission, represented the Methodists.

The Yirrkala Bark Petitions.

In 1962 Edgar and Ann Wells arrived at Yirrkala, accepting the challenge of replacing the retiring Superintendent.

“My acceptance of the appointment was a quite deliberate decision made with all the old-fashioned values associated with a sense of ‘call’”, Edgar Wells wrote later. “However, included in the theology of our response were certain sociological interpretations which we shared. We had come to believe that in the search for wholeness in the Aboriginal community, a place for Jesus of Nazareth as person of social and political sorrows must be found.”

Not long after the Wells’ arrival in Yirrkala, Aboriginal anxiety about mining exploration was expressed to them. “Aboriginal people became very disturbed by a survey peg on Bremner Island, a place of ‘important mythological associations”.

Harris’ narrative speeds up. In January 1963 Edgar Wells wrote to Arthur Calwell, the ALP leader of the Opposition asking that the Yirrkala Aborigines “receive protection.”

A month later, Prime Minister Menzies announces that the Gove Bauxite Corporation had been granted mining leases and the same day, the Methodist Mission Board ratified an agreement to mine. “No aboriginal person was present at the meeting. No aboriginal people were informed afterwards.”

When Wells subsequently received Arthur Calwell’s reply, he was shocked. The map of the mining lease, forwarded by Calwell, reduced the mission to two square miles and many of the Yirrkala people’s cultural sites were in the area marked for mining.

A later decision soon squeezed the mission into half a square mile. Wells sent a telegram to newspapers and organisations in the South including these words: “… 583 nomads now squeezed by the bauxite land grab into half a square mile stop original holding 200 square miles stop … loss of cultivated and grazing land means we must eat the cattle before the miners arrive and import basic food crops afterwards. Signature Wells Superintendent.”

This soon attracted media attention and questions in Parliament. The Methodist Board through Gribble wrote that “it seemed impossible to oppose the mining grant because too much was involved”.

“By April 1963, the disharmony between Wells and Gribble came to a head. Gribble completely excluded Wells from any discussions and denied him any further information on negotiations with the mining company. Mining officials were told that Wells need not be contacted as he had no power to make any decisions about the mission.”

“The legal process continued until, on 8 May, 1963, it was Wells’ ‘melancholy duty’ to read to the Yirrkala Aboriginal people the announcement in the Commonwealth Gazette that 140 square miles of their territory had been proclaimed a mining lease.”

Harris adds that about this time the Yirrkala people began meeting more formally and putting their thoughts on paper, using an old typewriter a departing missionary had given to Wandjak, the son of Mawalan, a noted artist and important clan leader.

A new church at Yirrkala with impressive Aboriginal paintings impressed an important visitor in July 1963. Kim Beazley (who had introduced a motion in Federal Parliament calling for recognition of Aboriginal land) heard that the Yirrkala people wanted to petition the Prime Minister. He suggested to the people that the petition be a bark painting. The typescript at the centre of the petition was typed on Wandjak’s old typewriter.

Wells was careful to take no part in the creation or the handling of the bark petition which turned out to be wise. When it was presented to the Federal Parliament, some MPs made the accusation that it was in fact Wells’ work.

More significantly the petition rapidly achieved international renown. In the short term, it led to a Senate select committee, which recommended compensation for the Yirrkala people — but the report was tabled and never acted on. “In the long term”, Harris recounts, “the Yirrkala bark petition was of great significance … It prepared people for the next two events to gain national and international publicity for Aboriginal land rights. The first of these events was the strike by members of the Guringji tribe working in the pastoral industry on Lord Vestey’s Wave Hill Station in 1966. The second was the Aboriginal Embassy, set up on the lawns of Parliament house in 1972.”

Within a few days of the Senate Committee’s findings becoming public, Wells was given notice by the Methodist Board to leave Yirrkala. Wells refused the transfer and was sacked. Gribble was awarded the OBE shortly afterward for “work for the advancement of the Aboriginal People of Australia”.

Many Methodists, Harris reports “felt uneasy, even angry about the whole affair, especially when it became more public that the Methodist church held investments in Queensland mines.” Harris reports that Wells was more pleased with the words of Wandjak the owner of the old typewriter: “The Wells’ were the only missionaries who really wanted to help the Aborigines.”

For wider Australia, the story of the Yirrkala Bark petition marks the beginning of the Aboriginal Land Rights Movement. For Missionaries and their supporters, it marked a turning point when Missionaries “began to see that the role of protector, no matter how benevolent or well-intentioned was outdated”. Missionaries were now free to be the friends—and servants—of aborigines, rather than relating to them from a position of power.

John Harris’ One Blood is available as a ebook on iTunes.

For more, see an interview with John Harris on Christianity and Aborigines with the Centre for Public Christianity.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?