Secret notes hidden in the text of England’s first printed Bible reveal that the Reformation was a gradual process rather than a clean break from the authority of Rome as had been widely assumed.

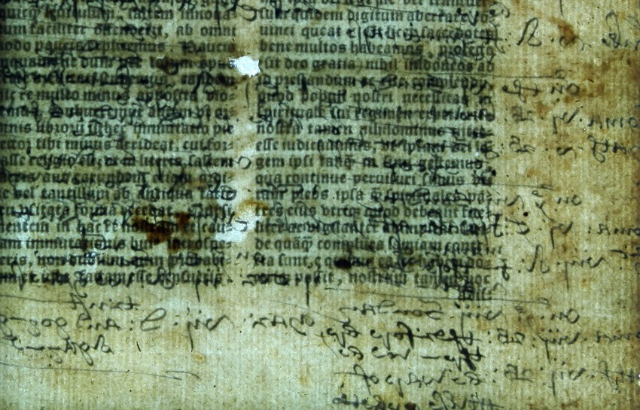

British researchers discovered the notes in a rare Bible at Lambeth House, the London home of the Archbishop of Canterbury and used complex image analysis to uncover them.

The notes, which had been hidden for almost 500 years, point readers to Latin texts of Bible readings for use in services, indicating that parishes were attempting to get around King Henry VIII’s ban on Latin in the liturgy.

On first examination, the Lambeth copy of the 1535 Bible, printed by Henry VIII’s printer, appeared clean, said historian Eyal Poleg, of Queen Mary University of London (QMUL).

“But upon closer inspection I noticed that heavy paper had been pasted over blank parts of the book,” he said.

“The challenge was how to uncover the annotations without damaging the book.”

With the assistance of Graham Davis, a specialist in 3D X-ray imaging at QMUL’s School of Dentistry, they took two images in long exposure, one with a light sheet slid between the pages and one without.

The first showed all the annotations scrambled with the printed text; the second showed just the printed text. Davis then wrote a piece of software to subtract the second image from the first, leaving a clear picture of the notes.

The annotations were written between 1539 and 1549, the most tumultuous years of Henry’s reign. This period included the move away from the Church of Rome, the Act of Supremacy, the suppression of the monasteries and the executions of Anne Boleyn, Thomas More and John Fisher.

In 1600 they were hidden and disguised under heavy paper.

“Until recently, it was widely assumed that the Reformation caused a complete break, a Rubicon moment when people stopped being Catholics and accepted Protestantism, rejected saints, and replaced Latin with English,” Poleg said.

“This Bible is a unique witness to a time when the conservative Latin and the reformist English were used together, showing that the Reformation was a slow, complex, and gradual process.”

Poleg was also able to trace the subsequent life of the book from a hidden note on the back page – a handwritten transaction between William Cheffyn of Calais, and James Elys Cutpurse of London. Cutpurse, in medieval English jargon, means pickpocket. The transaction states that Cutpurse promised to pay 20 shillings to Cheffyn, or would go to Marshalsea, a notorious prison in Southwark. In subsequent archival research, Poleg found that Cutpurse was hanged in Tybourn in July 1552.

“Beyond Mr Cutpurse’s illustrious occupation, the fact that we know when he died is significant. It allows us to date and trace the journey of the book with remarkable accuracy – the transaction obviously couldn’t have taken place after his death,” Poleg said.

He added: “The book is a unique witness to the course of Henry’s Reformation. Printed in 1535 by the King’s printer and with Henry’s preface, within a few short years the situation had shifted dramatically. The Latin Bible was altered to accommodate reformist English, and the book became a testimony to the greyscale between English and Latin in that murky period between 1539 and 1549.

“Just three years later things were more certain. Monastic libraries were dissolved, and Latin liturgy was irrelevant. Our Bible found its way to lay hands, completing a remarkably swift descent in prominence from Royal text to recorder of thievery.”

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?