‘I decided to lose my life and find it in Christ’

Springboks captain Siya Kolisi’s moment of truth

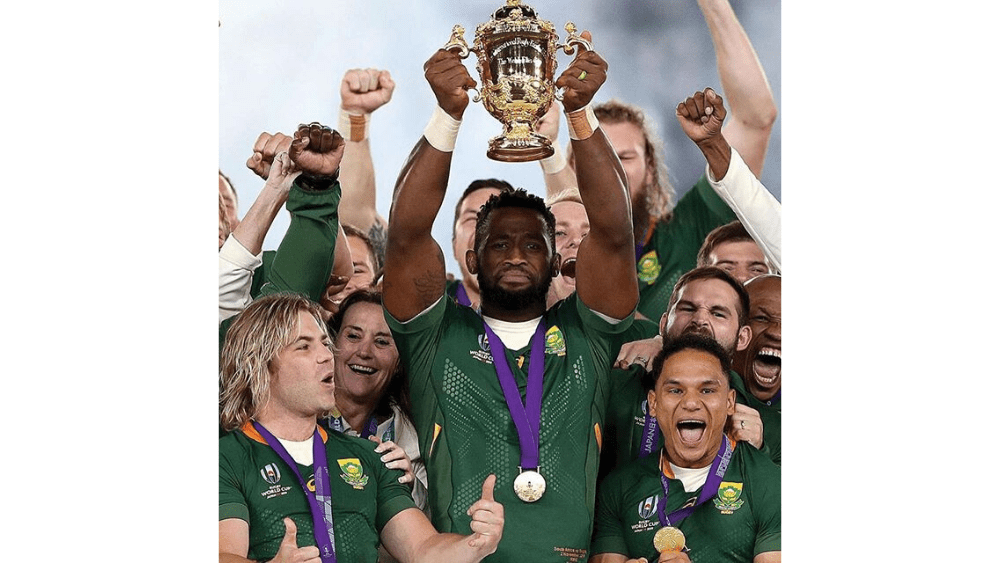

When Springboks captain Siya Kolisi hoisted the Webb Ellis Rugby World Cup trophy in Japan last Saturday, he was clearly experiencing one of life’s highest mountaintops, one that brought glory to his country of South Africa and to his teammates.

But just eight months ago, the 28-year-old was ensnared in one of life’s lowest valleys as the scandals of his personal life became tabloid news. That was when Kolisi says he really discovered the truth and saving power of Christ.

For anyone who isn’t a Rugby Union fan, Kolisi is the first black captain of South Africa’s Springboks rugby team, which clobbered England 32 points to 12 in the World Cup Rugby final.

Such a victory would be a huge achievement in any country. But it’s even more significant in South Africa, where rugby historically has provided the country with symbolic moments of national unity that are desperately needed as it attempts to heal the deep wounds of apartheid.

“His [Siya Kolisi’s] story about where he’s come from shows how far the country’s come.” – John Smit

“The hard thing to explain outside of South Africa is what a Springbok win in a World Cup in the past has done for unification and us continuing on this road of democracy and in new pathway,” former Springboks captain John Smit explained in a BBC interview.

“His [Siya Kolisi’s] story about where he’s come from shows how far the country’s come.”

And it’s not just a story of overcoming racism but also of overcoming the poverty that resulted from that racism.

Raised by his grandmother because his parents were teenagers, Kolisi grew up in the impoverished township of Zwide.

“Living in the ghetto, we struggled to get by. We couldn’t afford to pay for my school and all the fees that went along with it, but I went to school every day because it was where I received my one meal for the day. In the evening, I would return to our two-bedroom home where seven of us lived, take the cushions off the couch and sleep on the floor for the night,” Kolisi says.

He began to play rugby at the age of eight and, at 12 years, his natural talent caught the eye of the coach of an opposing team. The coach took him under his wing and mentored him as a player.

“I went to school every day because it was where I received my one meal for the day.” – Siya Kolisi

“He took me to my first provincial trial, where I played in boxers because I couldn’t afford rugby shorts,” remembers Kolisi.

Kolisi watched last Rugby World Cup from a tavern as his family couldn’t afford a television. This year, South Africa flew his father, Fezakel Kolisi – who 26 hours before the match didn’t have a passport and had never flown anywhere overseas from his South African township to Yokohama, Japan – to watch his son lead his team to victory.

“His story is unique. Previous generations of black rugby players weren’t given the same opportunities purely because of South African laws. He’s living the dream of people who weren’t given the same opportunities as him … and he’s grabbed those opportunities,” said Springboks ex front-rower Hanyani Shimange, who has known Kolisi since he was 19 years old.

Shimange describes Kolisi as a lover of rugby who is loved by the team and is “a good man, a humble man” with “a lot of time for people”.

“He’s uniting our country, our nation. The whole of Africa’s behind South Africa and Siya’s in the front of that,” he says.

In a piece Kolisi penned for Sport Go Mag in September, he said God “has been preparing me for such a time as this”.

“While I grew up going to church with my grandmother, and went off and on the past few years, it wasn’t until a few months ago that I truly gave my life to Christ. While struggling with a lot of things personally – temptations, sins and lifestyle choices – I realised I wasn’t living according to what I was calling myself: a follower of Christ. I was getting by, but I hadn’t decided to fully commit myself to Jesus Christ and start living according to His way. That is, until something I was struggling with in my personal life was exposed to the public,” write Kolisi.

“I knew I either had to change my life, or lose everything. I decided to lose my life and find it in Christ.” – Siya Kolisi

That personal struggle came to a head in March this year when Kolisi’s wife Rachel found revealing photos from a woman in her husband’s Instagram direct messages. She then took to Instagram to ask followers to help her locate the woman’s details. The mother of four went on to post videos in her Instagram story expressing her anger over the situation, before eventually deactivating her account.

“Up to that point, everything I was fighting against was hidden, but when my sin was exposed, I knew I either had to change my life, or lose everything. I decided to lose my life and find it in Christ,” Kolisi says.

“Walking alongside a spiritual mentor, I’ve been able to discover the truth and saving power of Christ in a whole new way. This new life has given me a peace in my heart I’d never experienced before. Now that I have given everything to God, nothing else affects me. I now live and play with the freedom of knowing His plan will always happen, and at the end of the day, that’s all I care about!”

The skipper also indicated how he would shoulder the weight of his nation’s World Cup hopes, writing:

“I don’t have to understand everything in life, and there are so many things I don’t … but I know God is in control of it all. My job is to do the best I can and leave the rest in His hands …

“If God can come through for countless people throughout history who had their backs against the world, He can do the same for me.”

The Springboks win has put the image of Kolisi holding the World Cup trophy in the history books alongside two other iconic moments. The first was when Nelson Mandela famously celebrated with Francois Pienaar at Ellis Park in Johannesburg in 1995 after the Springbok’s win at the Rugby World Cup. The second was when John Smit did the same with Thabo Mbeki in Paris in 2007.

But on both those two historic occasions, while the black players may have symbolised a nation heading towards racial equality, the reality was that there was just one black player in the 1995 team and two in 2007.

“We came together with one goal and wanted to achieve it.” – Siya Kolisi

This year, with a record six black players in the team, there are plaudits for the first national side where race hasn’t influenced the selection process.

“[There are] so many problems in our country, but to have a team like this … we know we come from different backgrounds, different races, and we came together with one goal and wanted to achieve it,” Kolisi said after the win.

“I really hope that we’ve done that for South Africa, to show that we can pull together if we want to work together and achieve something … We love you, South Africa, and we can achieve anything if we work together as one.”

Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the Nobel prize winner and anti-racism activist, described the win as providing “a welcome moment of optimism,” and pointed to the work still ahead.

“Though there has been much progress since the dark days of apartheid, South Africa remains one of the most unequal countries in the world, and deep tensions between communities remain. Violent crime is a serious problem, with poor people most likely to be victims. There is deep public frustration with soaring unemployment, low economic growth, patchy delivery of basic services and widespread corruption,” he said.

“We are a special country, and an extraordinary people. On days such as this we understand that when we pull together the sky is the limit. When we believe in ourselves we can achieve our dreams.”

Image of Nelson Mandela and Francois Pienaar after 1995 Rugby World Cup displayed in Apartheid Museum, Johannesburg, South Africa. Image: Kandukuru Nagarjun /Flickr. Flickr1 License

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?