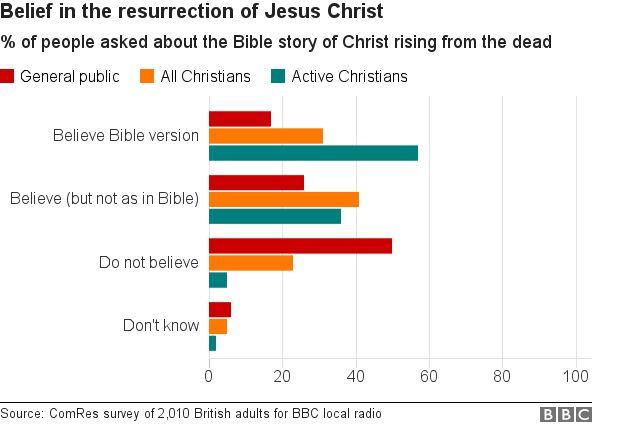

A quarter of people who describe themselves as “Christians” in Great Britain also say that they do not believe in the resurrection of Jesus Christ.

The figures have been released by the BBC, as part of a broader survey about life after death and general church attendance.

31 per cent of Christians believe word-for-word the Bible version, with that number rising to 57 per cent among ‘active’ Christians (those who go to a religious service at least once a month).

BBC study on beliefs about the resurrection BBC

People were asked to choose whether they believed in the resurrection of Jesus “word-for-word” as described in the Bible, whether they believed it happened but that some of the Bible content should “not be taken literally”, whether they did not believe in the resurrection or whether they did not know.

Half of all respondents (a total of 2010 British adults) said they did not believe in the resurrection at all.

In late 2015 the Church of England released a similar survey showing that 40 per cent of people in England do not believe Jesus was a historical figure, 22 per cent believe he was a “mythical or fictional character,” and 18 per cent do not know.

When it came to the resurrection, that 2015 survey showed 43 per cent of respondents said they believed in it. But many believed the biblical story contained elements that should not be taken literally.

This week’s British results results come on the heels of a study by Barna in the U.S. that investigated what religious faith outside of institutional religion looks like and what spirituality outside of religious faith looks like.

There is a large cohort of people in the South, Midwest and Western parts of the U.S. who say that they “love Jesus but not the church.”

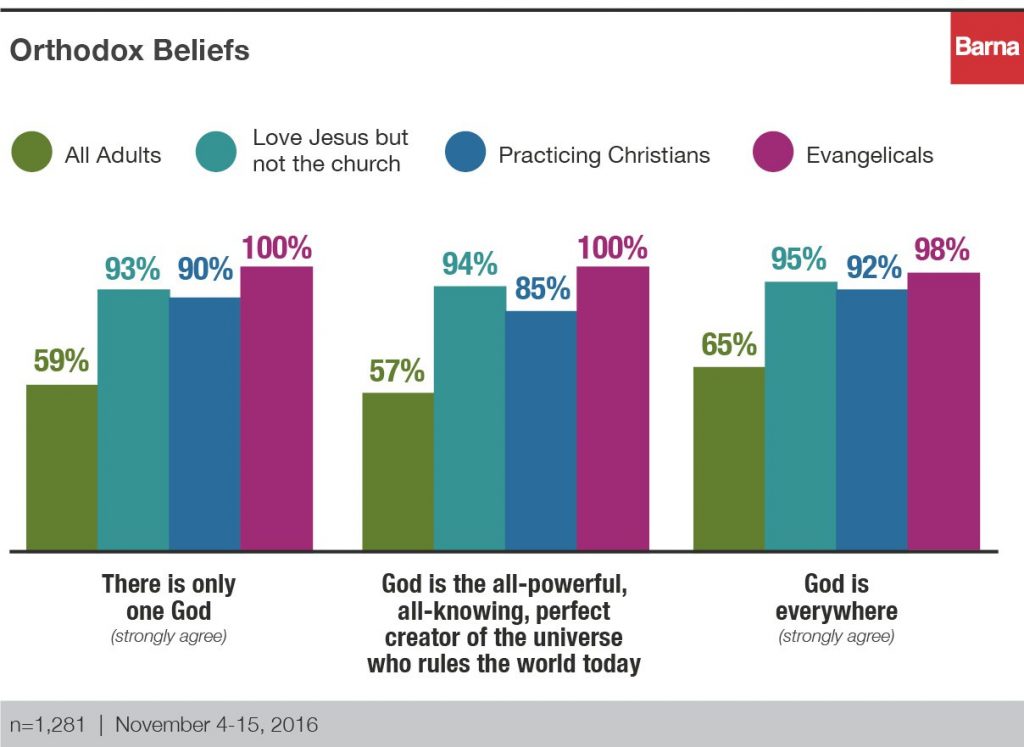

The Barna study shows that, “Despite leaving the church, this group has maintained a robustly orthodox view of God. In every case, their beliefs about God are more orthodox than the general population, even rivalling their church-going counterparts.”

Orthodox beliefs of those who “love Jesus but not the church” Barna

They still actively practice their faith, but in less traditional ways.

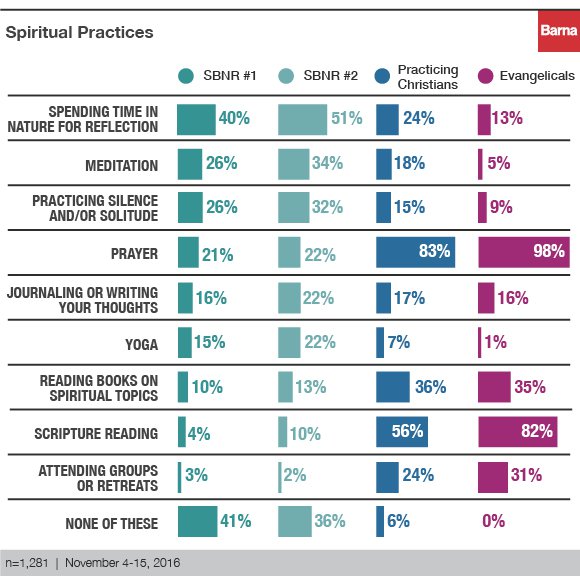

People in this group generally maintain an active prayer life, but read the Bible significantly less than the average practising Christian. The study suggests “this all points to a broader abandonment of authoritative sources of religious identity, leading to much more informal and personally-driven faith practices. They are certainly still finding and experiencing God, but they are more likely to do so in nature, and through practices like meditation, yoga and silence and solitude.”

Roxanne Stone, editor in chief of Barna Group, says, “The critical message that churches need to offer this group is a reason for churches to exist at all. What is it that the church can offer their faith that they can’t get on their own?

“Churches need to be able to say to these people — and to answer for themselves — that there is a unique way you can find God only in church. And that faith does not survive or thrive in solitude.”

Going one step further, the Barna study also explored the identity of those who consider themselves “spiritual but not religious.”

This group of people — defined as those who self-identify as “spiritual” but are either irreligious or say their religious faith is not very important in their life — generally hold to much looser ideas about God, spiritual practices and religion.

They are just as likely to believe God represents a state of higher consciousness that a person may reach as they are to believe God is an all-powerful, all-knowing, perfect creator of the universe who rules the world today. They also are just as likely to be polytheistic (belief in more than one god) as monotheistic (belief in only one god).

“But straying from orthodoxy is not the story here. This feels expected. Sure, their God is more abstract than embodied, more likely to occupy minds than the heavens and the earth.

Spiritual practices of those who are “spiritual but not religious” Barna

“But what’s noteworthy is that what counts as ‘God’ for the spiritual but not religious is contested among them, and that’s probably just the way they like it. Valuing the freedom to define their own spirituality is what characterises this segment,” says the study.

“Those who love Jesus but not the church are certainly more favorable toward religion and would likely be more receptive to re-joining the church. Yet, spiritual leaders should not discount this group of the ‘spiritual but not religious.’ They are distinct among their irreligious peers in their spiritual curiosity and openness,” says Stone.