What happens after the last Christian? Australia, secularisation and God

What’s the truth about secularisation? – Eternity is pleased to present a powerful address that Rory Shiner, senior pastor of Providence City Church in Perth, gave last week to Freedom19, a conference for Christian think tank Freedom For Faith.

At some stage in history, there was a funeral at which the last active believer in Thor was buried by children who no longer shared their faith.

That must have happened. And when it did, it was a momentous event in the history of Nordic culture. Yet history has left us no record of it. Perhaps, like the last time you rode on your father’s shoulders, or the last time you played a game of hide-and-seek, there was no way of knowing it was the last time. But that last funeral of the last believer in Thor must have happened, even if those present were not aware of the historical weight of that moment.

Australia and the last Christian

If, some years from now, the last Christian in Australia is buried by children who no longer share their parent’s faith, what will that moment mean? Will it matter if Australia loses God – the God of Christian faith?

2067: The last British Christian

Damian Thompson, in a 2017 article in The Spectator, calculated that Christianity will end in Britain in the year 2067.

Now, as Thompson acknowledged, the chances of that literally being true are remote. Immigration continues to bring, both to Australia and to Britain, people who are significantly more religious than the nations to which they come. And, based on demographic trends alone, the world seems set to become more rather than less religious in the coming decades. And any linear extrapolation of this sort of data is bound to come up against the decidedly non-linear patterns of history. Like Thompson, I am using the idea of the last Christian funeral to focus our question.

Secularisation

When we think about the future of Christianity and of religion in Australia, we are thinking about a process called secularisation.

The word “secular”, curiously enough, is a word that comes out of Christian theology.

“Secular” means “of this age” or “of this world.” Christianity emerged in the Roman Empire, in a context where a civil code was already in place. It did not, like Judaism and Islam, need to build an entire civil code. Christianity was born within a state; it did not need to give birth to a state.

However, in its convictions, Christianity is a decidedly public religion. Through belief in a creator God, it has something to say about everything. This included those public spaces over which it did not exercise control but in which Christians believed their God was present and active.

Out of this, a theological distinction emerged between what was proper to this age (“secular”) and what belonged to the age to come. (In the Catholic tradition it is possible to speak of “secular priests” as opposed to “religious priests”- the secular priest working in a parish, and attending to the needs of the people in this age, while the religious work in a monastery, in prayer, oriented towards the age to come.)

This ability to distinguish the secular from the sacred, the Church from the State, has been described by Rabbi Wolpe as one of Christianity’s greatest gifts to the world.

Sometimes, of course, as our children become independent, they go off in directions we did not anticipate and perhaps do not always endorse. The idea of the secular is a case in point. What was once an important tool of Christian theology has become, over time, something rather different.

The secularisation thesis

Most Western nations are understood to be going through a process of becoming less religious, a process called “secularisation”. The easiest way to demonstrate this is through a decline in religious institutions – in fewer people going to church, mosque or synagogue. And, if that is the measure, it would seem some sort of secularisation is happening. Sort of.

Sociologists speak about belief, belonging and behaviour as the great trifecta of religious life. Religion involves believing certain things to be true but also belonging to a community or institution and adopting certain behaviours.

Simply by including those three measures, the apparently simple proposition that Australia is becoming more secular and less religious becomes more complicated. As sociologist Linda Woodhead has said, to argue modern society is less religious on the basis of a decline in institutional affiliation is a bit like arguing that modern society is less enthusiastic about communication on the basis of the steep decline in the use of telegrams.[1]

Stories of secularisation

Most of us in Australia carry in our heads a story about the place of religion and of secularisation.

When I use the word “story”, I don’t mean “fiction” as opposed to “non-fiction”. I am using “story” in the way philosopher Charles Taylor uses the word. Stories are the way we gather facts, events, thoughts and opinions into a narrative in order to discover their meaning. We humans are very reluctant to see history as just “one damn thing after another”. We search for meaning, and meaning is delivered in stories. As the great atheist fantasy author Phillip Pullman has said, the world is shaped more by “once upon a time” than it is by “thou shalt not.”

The subtraction story

We modern Australians carry in our heads a powerful default story about the place of religion in our society. It is a story that Charles Taylor has called “The subtraction story”. The short version is that science beat religion. The longer version goes a little something like this:

Once upon a time in the West, everyone believed in God. But then something changed. In the 1600s, a new way of acquiring knowledge, the scientific revolution, began. This way of knowing was extremely successful, and people began to emerge out of the religious fog.

The 1700s was the age of enlightenment, when this new epistemology was applied beyond science to morality, government and society, with great effect.

In 1859, Darwin published The Origin of Species and, with it, the last great claim of the Christian faith – the claim that humans occupy a unique, God-given place in the universe – crumbled.

Then, finally, the 20th century bought modernity: democracy, free markets and technology. With modernity, secularisation just comes with the factory settings. Religion, to quote Christopher Hitchens, is humanity’s “first and worst” attempt at explaining the world. It cannot co-exist with modernity. It will either become literally extinct, in the way that the worshippers of Thor are now extinct, or it will become so marginal, even in the lives of those people who believe, that it will one day be functionally irrelevant. Set your calendars. The last Christian funeral will shortly begin.

“Census no religion”

We saw this story powerfully conveyed in the “Census no religion” campaign of 2016.

The campaign itself was a good faith initiative to encourage people who had no religion to say so in the census. As a question seeking more accurate information, it was laudable.

But notice the language used in the campaign:

“Not religious any more?”

If the sign had said “Not religious?” it would be merely an information campaign. But add the words “any more” and the sentence comes alive. Now it’s not mere information. It’s a story.

The rhetorical effect is similar to the 2016 Trump campaign slogan “Make America Great Again.” Remove the word “again” and the slogan becomes a pedestrian statement. “Make American Great.” Sure. Whatever. Who cares? But add the word “again”, and the phrase becomes a story. American was once great. But somehow it lost its way. Now a hero has arisen to restore order to the universe by making America great again.

The phrase “not religious any more” taps into a similar kind of story. Once upon a time, we were all religious, but the fog is lifting. Lots of people aren’t religious any more. How about you?

Charles Taylor calls this a “subtraction story”. It sees religion as an easy-to-identity set of objects which, once removed, leave the rest of the society more or less where it was.

It’s as if an advanced Dyson vacuum cleaner set to “religion” were making its way through our society. Like any vacuum cleaner, it can’t get everything – there are still places under the fridge and behind the couch it can’t quite reach. However, it’s doing a pretty good job of getting religion out of all the places you can see. The rest of the furniture is basically where it was. We’re the same people doing the same stuff in the same way; we’re just not religious, any more.

Australia and the subtraction story

The subtraction story is the dominant story in our culture. And when we look at the data for Australia, the story seems to check out. Kind of.

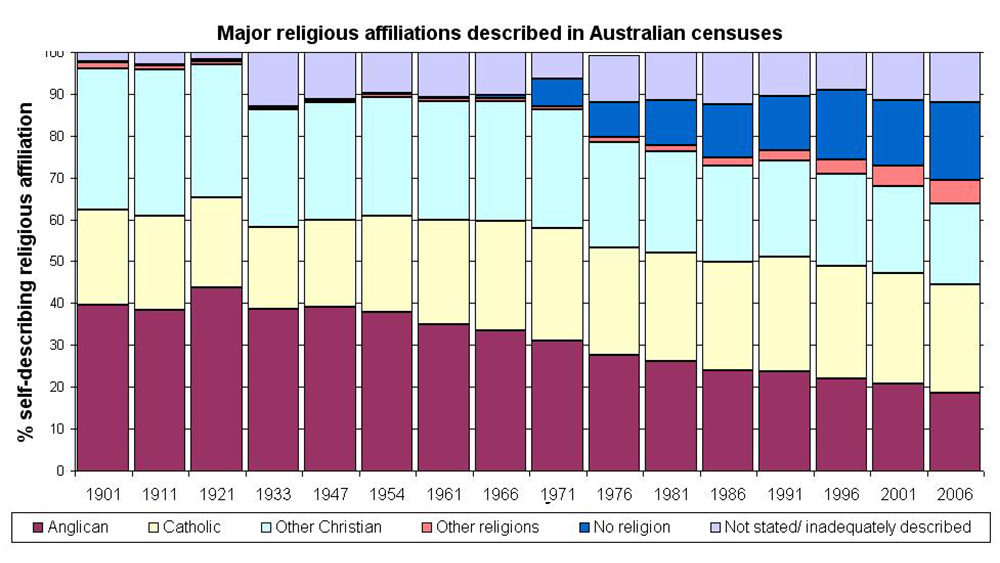

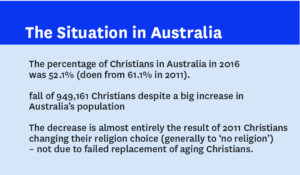

At Federation (1901) Australians identified as 96 per cent Christian. By 1954, that figure was down to 89 per cent. Then, the most recent data shows something dramatic. Between 2011 and 2016, those identifying as Christians went down to 51 per cent. According to McCrindle, this is the biggest drop of anything ever measured in the census. This decline has not been slow and steady but sudden and dramatic. So far, so good for the “not religious any more” account.

But here’s where it gets interesting. This story of decline in people identifying as Christian has very little relationship to the life and vitality of Australian churches. The churches have been, in the best sense, all over the place. They’ve had moments of vitality and moments of decline all of their own. Indeed, in the postwar era, from 1945–1963, while Christian identification was going slowly down, the churches were actually experiencing a time of revival, growing on almost any indicator you care to measure.

What about behaviour? In his recent magisterial book, The Fountain of Public Prosperity, Australian historian Stuart Piggin has argued that Australia is one of the most Christianised nations on earth in terms of the prevalence of Christian values in the culture.

This is not our self-understanding. Why? In a survey of Australian historians in the mid 1980s, 48 per cent reported that they were atheists and a further 12 per cent said they were agnostic. Compare that to the figures for the general population in the same period, where only 0.8 per cent of people said they were atheists and 1.7 per cent that they were agnostics. These figures are wildly out of sync. It’s hard to believe our self-understanding has not been affected.

What do we make of the recent dip in Christians from 2011? Put concretely, about 950,000 who said they were Christian in 2011, said they weren’t in 2016. Where did they go? Were those 950,000 people active in churches in 2011? Were they reading their Bibles, serving the poor and evangelising their neighbours until, at some point between 2011 and 2016 they thought, “Oh, forget this, I’m becoming an atheist”?

That’s not what happened.

Overwhelmingly, those 950,000 did not change their religious patterns but their identity. Church attendance remained fairly constant in the same period. But for whatever reason, 950,000 people, who in 2011 to said, “What are we again, honey? Was it Church of England?” by 2016 felt emboldened to say “I’m not really sure what I am. I’m just going to tick ‘No religion’.”

Holes in the story

Some version of the subtraction story dominates our imaginations. But how true is it? How well does it account for the evidence? I think, with some difficulty. Let me give you just three examples.

A Golden Age of Faith?

First, the subtraction story relies on the notion of a Golden Age of Faith – a time when religious belief was ubiquitous and uncomplicated in the West. How true is that? The answer is, not as true as we might think.

The evangelisation of Europe was, in fact, a long, slow, and erratic process. Even as Christianity was formally adopted by rulers, the process of genuinely catechising the population into the faith was often thin and faltering.

Many priests were uneducated and, not actually knowing Latin, would mumble through the service with Latin-sounding words. A report from the 1500s says that:

Members of the population jostled for pews, nudged their neighbours, hawked and spat, knitted, made coarse remarks, told jokes, fell asleep, and even let off guns.

One man was charged with misbehaviour in church because of his “most loathsome farting, striking, and scoffing” which apparently had people cheering for him in the church service. Perhaps our forebears were not as pious as we imagine?

Troubling non-correlations

Secondly, does the data behave in the way the story would predict? The answer is, not really.

Actually, the Age of the Enlightenment was also the great age of Christian expansion, the time of the birth of evangelicalism, and an age of revivals.

In the 19th century, after the publication of Darwin’s Origin of Species, religious belief and practice actually went up. According to some scholars, Britain reaches peak Christianity not in 1066 or the 12th century or the 1600s but rather the year 1901 – an odd result if it was “science wot did it.”

And currently, tertiary education makes church attendance in Australia more rather than less likely. The more educated you are, the more likely you are to attend church. Karl Marx famously argued that religion was the opium of the masses:

Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.

This is a rather tender take on religion from Marx. It reflects a common take – that religion is irrational but serves a purpose for the underprivileged and undereducated. But it’s a take that’s hard to correlate with the actual patterns of church attendance in contemporary Australia.

The problem of the exceptions

Thirdly, there is the problem of the exceptions. The traditional secularisation thesis has always recognised the odd exception of the United States – a modern, prosperous Western nation which remains deeply religious.

But in the latter half of the 20th century, more and more exceptions had to be added to the list – Southeast Asia, the Middle East, China. These have all been places where modernity does not seem to exclude religion in the way the theory might have predicted. Indeed, the exceptions are so many that some scholars now talk about the western European exception.

A reframing story

And so, for what it’s worth, I follow Charles Taylor and others in believing that the more plausible story is not a subtraction story but rather a reframing story.

In this account, our path to secularisation was not that religion was our “first and worst” attempt at explaining the world. Rather, the path to a secular age has been long, meandering and complex, wherein science, art, poetry, culture, clocks, aspects of Christian theology, wars, economics, architecture, philosophy and reproductive technology have taken our culture on a non-linear, contingent and erratic journey to our current secular moment.

What has changed is not so much our beliefs as such but our conditions of belief – the things we think before we have started thinking. Modern life is captured by what he calls “an immanent frame”. Transcendence has not been reasoned out so much as it has been framed out of modern existence.

Frames (think of a picture frame) don’t tell you whether or not there is anything outside the frame. They are not competent to do so. What they do is direct your attention to a certain limited area. They say, in effect, “Look here! Ignore what’s out there for the moment; focus on this.”

For Taylor, it’s possible to have an “open” or a “closed” spin within the immanent frame. You can believe or not believe that there is a transcendent reality outside the frame. The frame says, “Don’t worry about that. Focus here.”

The immanent frame and the last Christian

I believe what has happened in Australia is not that “religion” has been, or is being, vacuumed out of public space by the rational processes of modernity. Nor do I think the final word has been spoken on transcendent truth-claims. It wasn’t “science wot did it.” If you will permit the dad joke, science was framed. We all were. Modernity has framed us. But frames are not cages. There are ways out. “Open spins” are possible. Sometimes they flourish, even in the immanent frame.

Changes in Australia

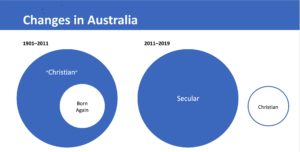

Something has changed. What is it? I believe it is not the possibility of religious convictions as such but the nominal Christian consensus.

The late, great Les Murray described Australia as “roughly Christian”.

It was once a country in which most people thought of themselves as Christian. The division was between nominal and active Christians. When the evangelist Billy Graham came to Australia in 1959, almost all his messages were about the need to be “born again”. The New Testament speaks of being born again only two or three times and yet it was at the heart of Graham’s message. Why? Because Graham was speaking to a “roughly Christian” nation. When you are speaking to people who are “roughly Christian”, you need to draw a sharp distinction between nominal and active Christian faith.

Billy Graham: Are you a Christian?

Average Australian (until recently): Um, well I was baptised. I went to a church school. Is that what you mean?

Billy Graham: No. I mean, are you born again?

This is what has changed. We now live in a country where the pressure or desire to identify with Christianity has collapsed. That’s a real change. It is a mistake, however, to imagine the space left behind is a simple, common-sense space from which religion has been vacuumed out. The religious vacuum cleaner is not nearly that precise. It has left much of the religious furniture in place. And if that vacuum cleaner were to be more successful in eradicating what is specifically Christian, we might not much like the results.

The last Christian funeral?

Would it matter if Australia lost God?

First, the possibility is remote. For reasons I have given, as well as others I’ve not had the space or time to develop, the idea that modernity necessarily entails a post-religious future is a doubtful claim.

Secondly, a good-faith argument could be made that huge swaths of charitable work in areas such as education, care for the poor, ESL, refugee services, international aid, aged care, and other justice and mercy work are sustained by specific religious commitments – by people who have allowed their open take in the immanent frame to shape their beliefs and behaviours. To this we could add the quiet way in which local churches and other religious communities provide an antidote to something that appears to be a pandemic in secular culture, namely loneliness.

Since the postwar era, two institutions, the State and the Market, have, like two inflating balloons, taken up vast swaths of social real estate, greatly reducing the space left for voluntary associations. Such institutions, which sociologists call “mediating institutions”, and of which religious communities are the most sustained example, are crucial for a healthy society. A future in which almost everything is done either by the Market (which seeks a profit) or the State (which has a monopoly on legitimate violence) is vaguely terrifying.

Thirdly and finally, allow me to return to my scepticism about our imaginary religious vacuum cleaner. The idea that the removal of religion from the public square is a simple operation of removing eccentric and irrational ideas from an otherwise rational space is a fantasy. I would join my insignificant voice to figures as diverse as Jürgen Habermas, Tom Holland, Catherine Pickstock, John Gray, Edwin Judge, David Bentley Hart, Graeme Smith and others who have unmasked the story that our best moral instincts are products of the enlightenment. That they are what you have left when you’re not religious any more.

In which laboratory were human rights first discovered? By which experiment did we demonstrate the equal dignity of every human being? By which line of reasoning did we ground the claim that poor and the weak deserve special honour and care? Which aspect of Darwinian evolution established the notion that the voices of victims deserve special attention and honour?

The truth is that all of these are ideas whose origins and development are specifically religious, and mainly Christian. As atheist philosopher John Gray points out, taken-for-granted ideas such as free will, progress, the idea that humans are different from other animals, and that humans ought to steward the resources of the world virtuously, are each beliefs that “no one would think of taking seriously if it were not formed from cast-off Christians hopes.”

If religious ideas were to be successfully removed from the public square and from public life, one day we may wake up surprised at precisely which babies were lost with the religious bathwater.

This article was developed through lectures first given at St Bart’s Anglican Church, Toowoomba, and then in different forms at the UWA Christian Union and the 2019 Freedom for Faith conference. I thank each of those communities for their hospitality and their generous feedback.

[1] Paul Robertson has argued this is the case for millennials. Millennials are widely reported to be the least religious generation in history. And this seems to be true – but true only on the institutional measure. It turns out that when you drill down into the beliefs and behaviours of millennials, it may be that they are just as likely to believe in life after death, heaven and hell and miracles as other generations. So, while belonging is down, belief and certain behaviours, such as prayer, seem to be at least ambiguous.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?