Every Christian who is prepared to give an account of his or her faith – and the Apostle Peter tells us this should be all of us – has heard the charge that religion is behind most wars and that it promotes violence.

Both accusers and defenders often get this fatally wrong. The former tend to exaggerate and conflate all sorts of complex political and economic influences under religion, partly because it is easy and partly because it is useful.

Defenders often deny that religion, at least their own, can be guilty because it condemns violence. This version of the “no true Scotsman fallacy” – no Scot would do that, and if he did then by definition he could not be a Scot – is still very common with Muslims who deny that Islamic terrorists can be genuine Muslims.

…religion is not merely a set of stated beliefs but a way of life, and how its adherents actually live in the world cannot be separated from the religion.

William Cavanaugh, Professor of Theology at Chicago’s De Paul University, shows that this defence fails on two counts. First, it’s impossible to separate religious motives from the mix to make religion innocent and, in trying to do so, defenders fall into the same error as their accusers. How can you separate religion from politics within Islam when Muslims themselves make no such separation?

Second, any religion is not merely a set of stated beliefs but a way of life, and how its adherents actually live in the world cannot be separated from the religion. Religious people can be violent generally and even in the pursuit of their religion. The Crusaders may have misappropriated their faith, but it was their stated motive, just as it is for Islamic terrorists. Faith cannot be dismissed.

Cavanaugh, who last month gave the 2016 Richard Johnson Lecture in Sydney for the Centre for Public Christianity, observes that religion – an activity, after all, carried out by humans – is not innocent of violence or other human failings. Where the critics err, he says, is in suggesting religion is more violent than secular ideologies.

On a 2006 visit to Australia, Cavanaugh alerted me to a strange argument by distinguished American historian Martin Marty. In the 1940s, Jehovah’s Witnesses in the United States were beaten, tarred, castrated and jailed because they believed that followers of Jesus should not salute a flag. To Marty, this is evidence that religion has a particular tendency to be divisive and therefore violent.

…the division between religious and secular found in much modern political debate is a modern invention to separate religion from culture, politics and economics.

He writes that it “can be perceived by others as dangerous. Religion can cause all kinds of trouble in the public arena.” For Marty, religion refers not to the ritual pledging of allegiance to a flag, but only to the Jehovah’s Witnesses’ refusal to do so.

There is clearly something wrong here. Surely the obvious conclusion is that fanatical nationalism can cause violence. Marty blames religion because he is seduced by this myth of religious violence that is so deeply entrenched in Western society.

Cavanaugh argues that this myth plays a valuable role for secularists. It helps them marginalise Christians and demonise Muslims, and creates a blind spot about violence by the West. It confirms an “us” (the rational, peace-making, secular West) against a “them” (violent fanatics in the Muslim world). “Their violence is religious, and therefore irrational and divisive. Our violence, on the other hand, is rational, peace-making and necessary. Regrettably, we find ourselves forced to bomb them into the higher rationality.”

In fact, the division between religious and secular found in much modern political debate is a modern invention to separate religion from culture, politics and economics. If it can be separated, it can be separately attacked.

Yet religion is notoriously impossible to capture in a definition. Must it include God or gods? If not, Buddhism and Confucianism qualify but so do secular faiths such as nationalism or ecology.

So there is indeed a case for religion to answer when it comes to violence. But what is often left out of such discussions is religion’s extraordinary capacity in the opposite direction – to promote and build peace, reconciliation, understanding and generosity.

The sociologists, political scientists, historians, theologians and others who have written since 9/11 attacking religion as violent just pretend this difficulty does not exist. Then they claim religion is prone to violence because it is absolutist, divisive, and/or irrational. They ignore overwhelming evidence that secular ideologies and institutions can be just as absolutist, divisive or irrational.

But when they try to separate secular from religious violence, they refute their own distinctions. Marty lists five “features” of a religion, and then shows how politics shares all five: both focus our ultimate concern, both build community, both appeal to myth and symbol (for example, national flags, war memorials), both use rites and ceremonies and both demand certain behaviours. In showing how closely intertwined the two are, Marty ends up demolishing any theoretical basis for separating them.

When it comes to violence, secular religions such as nationalism or ethnicity (think Rwanda or Yugoslavia in the 1990s) have hands as bloody as any religion. How many Christians would be willing to kill for their faith? How many would be willing to kill for their country? Surveys in America show that the nation-state attracts far more absolutist fervour than Christianity. Many Christians there endorse slaughter on behalf of the nation.

Religion is about relationships, and so is solving problems of violence.

If this myth about religious violence is incoherent, why is it so widely believed? Because it’s so useful. In domestic politics, it helps silence religious believers, who are told their faith is a private matter and must be kept out of politics. In foreign politics, the myth helps reinforce and justify Western attitudes, especially towards Muslims. It enables us to demonise Muslims as primitives unable to separate religion and politics, thus cementing the “us and them” attitude and letting the West sanitise its own actions.

So there is indeed a case for religion to answer when it comes to violence. But what is often left out of such discussions is religion’s extraordinary capacity in the opposite direction – to promote and build peace, reconciliation, understanding and generosity.

Christ’s teachings about loving our enemies, doing good to those who hate us and turning the other cheek are profoundly counter-intuitive, but they have changed the world. They provide an aspiration and a praxis.

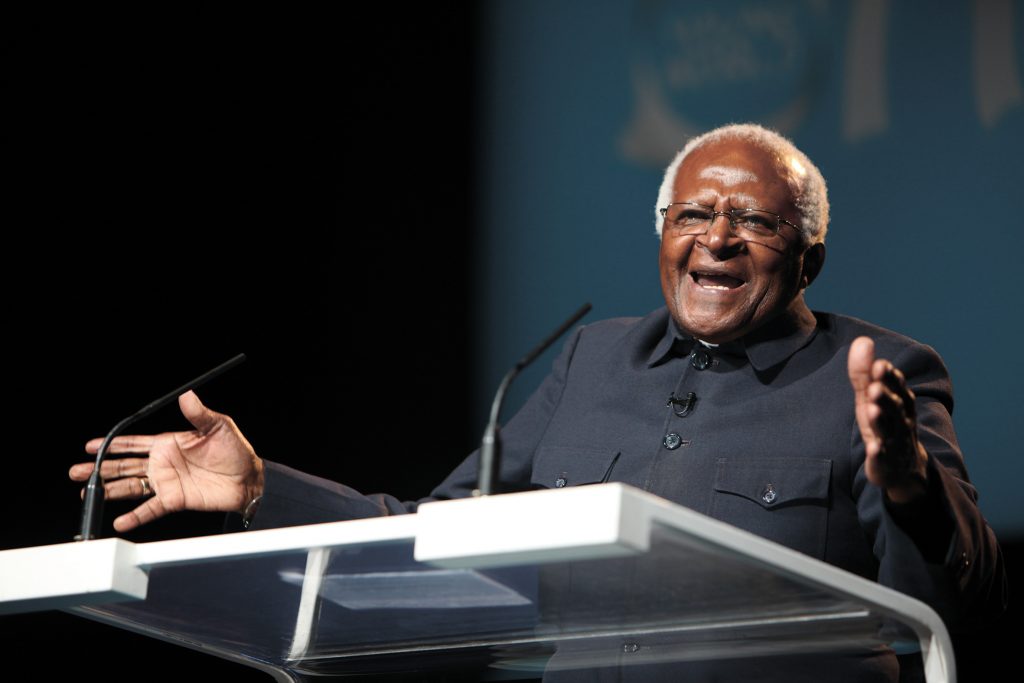

A prime example is South Africa, which could have easily degenerated into sanguinary civil war after the end of apartheid. Instead, motivated by their profound personal faith, President Nelson Mandela and Archbishop Desmond Tutu gave the nation its Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Lisa Schirch, a US professor of peacebuilding, has written that the commission “successfully guided South Africa through the perilous post-war context and created an atmosphere safe enough for perpetrators to ‘confess’ the truth of their crimes in exchange for amnesty”. It also limited the sporadic outbreaks of “street justice”.

“Religious leaders hold a tremendous ability to influence people through moral language that resonates with people’s basic values. In South Africa, the call for people to reconcile became a surround-sound campaign, with preachers linking faith with political transition every week and on radio stations across the country. … In many ways Christianity infused the entire TRC process.”

Religion is about relationships, and so is solving problems of violence. One thing Christians know is that “peacemakers who sow in peace reap a harvest of righteousness.” (James 3:18)

Barney Zwartz is a Senior Fellow of the Centre for Public Christianity.