A movie version of The Shack, the best-selling novel by Canadian author William Paul Young, will be released at Australian cinemas on May 25. This big-screen adaptation will rekindle The Shack as a hot and divisive topic among Christians, as it often has been since it was first published in 2007.

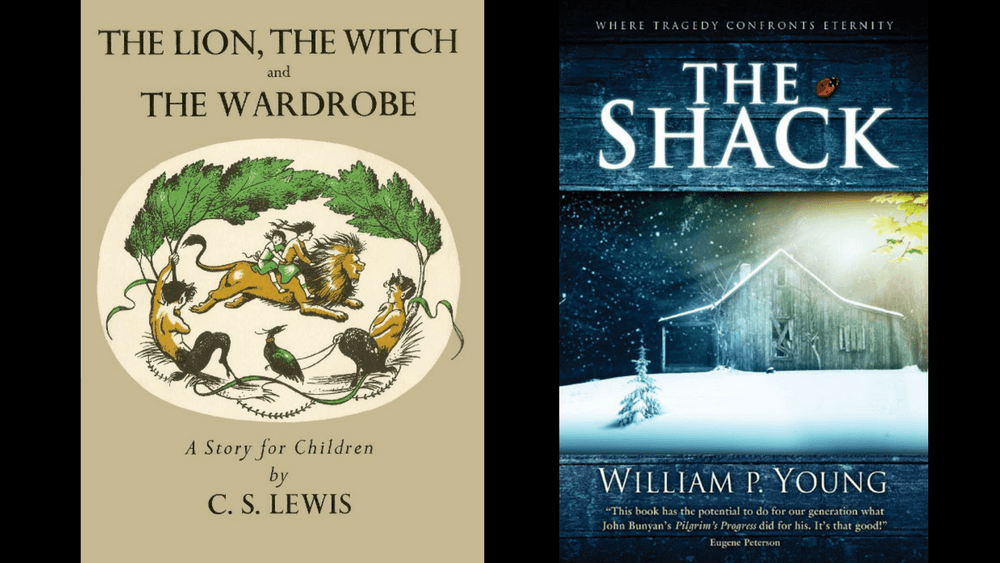

There’s nearly always a snag when fiction meets Christianity, even if it is a form of fan fiction. It could be Father Christmas appearing in C. S. Lewis’ The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe – which some Christians see as a flaw in that beloved allegory (a story with a not-so-hidden meaning). And if I had ever managed to get past the breakfast scene in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, I’m sure I would have found there would some things which some Christians find difficult too.

Most of the book is about God’s pursuit of Mack.

But let’s not rush to the controversy about The Shack as there’s actually a store of good things about it. Without giving too much away, The Shack introduces us to Mack, a man in pain. A parent’s nightmare has come true in his life and he has sunk into “The Great Sadness,” seemingly out of reach of the God who his wife, Nan, follows.

Most of the book is about God’s pursuit of Mack. Young convincingly portrays God’s care for this bitter man, and the lengths God goes to reach out to us. The love of God for this man is the most vivid thing in the book.

The German translation of the title, “A Weekend with God,” is a good summary of what happens. Mack is drawn to a shack in the woods and encounters God in a strange form of the Trinity: Papa, an African American Woman; Jesus, a Middle Eastern carpenter; and Sarayu, an Asian woman who represents the Holy Spirit. Most of the book is about their conversations.

Mack walks across a lake with Jesus, and he confronts his suffering. The Shack is good on suffering. Mack’s suffering is real. What he feared has really happened. As the poet Dante puts it, “Sometimes in the midst of life we are in a dark wood.” Suffering comes to the most devout of Christians as well as those on the edge of faith, such as Mack.

This book moved me to tears on the plane where I read it.

Through his experiences at the shack, Mack looks at what has happened from the viewpoint of eternity. He learns that God’s suffering provides for him. This book moved me to tears on the plane where I read it.

While God reaches out to Mack, Mack himself needs to come to terms with God – he needs to change. Mack needs to wrestle with God to understand himself.

One of the biggest snags about The Shack, for many Christians, is the odd Trinity metaphor that Young has created. The weird presentation of the Trinity points to the strangeness of God, who is not domesticated. Young was primarily writing for (speaking to) an American market, where the Christian Church remains largely segregated. Compare how white and black Christians voted at the last US election. Whatever one thinks of President Trump, this division in the body of Christ is troubling. So, it may be salutary to represent God as black, as Young does in The Shack.

Young’s Trinity is so bizarre, that it is obviously fantasy.

The Trinity is notoriously difficult to write about. Either someone will be able to draw what one can from Young’s treatment of it and move on, or they will find his treatment of it to be such a barrier that they cannot get passed it.

But like the wizards in the Harry Potter series, Young’s Trinity is so bizarre, that it is obviously fantasy. And if it is something you can suspend disbelief about, you might well be able to get into Mack’s story.

There is one odd absence in The Shack, though. For Christians, the Bible is key – but the constraints of the story line mean the Bible does not feature in Mack’s learning to trust God. But The Shack is only a story – remember there is no Bible in Narnia, either. Rather, it appears as the “older magic”.

A wide form of universalism occurs in The Shack.

We must recognise Lewis’ lion when he appears in our lives.

Young’s allegory is less worked out than Lewis’ – but that might simply be setting the bar too high. But a key comparison between Lewis’s writings and The Shack can be made. It concerns a scene in The Last Battle. Emeth, a worshipper of the false god Tash, is one of the invaders of Narnia. But he is a righteous man and when he encounters Aslan/Christ, the lion exclaims: “I take to me the services which thou hast done to Tash. For I and he are of such different kinds that no service which is vile can be done to me, and none which is not vile can be done to him.”

The idea of someone unconsciously serving the true God, is reflected in the Vatican II idea of “anonymous Christians”. This is regarded as a flaw in the Narnia books, by some Christians.

On a similar note, a wide form of universalism occurs in The Shack. Jesus in Young’s book says, “Those who love me come from every system that exists. They were Buddhists or Mormons, Baptists or Muslims … I have no desire to make them Christian, but I do want to join them in their transformation into sons and daughters of my Papa.”

A best seller and a movie that forces you to talk about God – there’s a lot of good in that.

According to a key critical review, “Burning Down the Shack”, written by the confusingly named James de Young (who debated universalism with author William Paul Young as he wrote The Shack), the aim was not to say all religions lead to heaven, but that God would eventually save anyone.

Whichever form of universalism Young intends, The Shack teaches that all are saved.

This is a key point to be prepared for when discussing the book or the movie with friends. To what extent the movie explores this theme is not known yet to Australian audiences but, in my view, it is unlikely to have gone missing.

Discussing this flawed allegory of Christianity is the point I want to leave us with, though. The Shack movie will reboot the discussion this year. But it is a discussion worth having.

A best seller and a movie that forces you to talk about God – there’s a lot of good in that.