Love overcomes evil in America’s Deep South

“Hate as a way of attacking hate is a no-win situation”

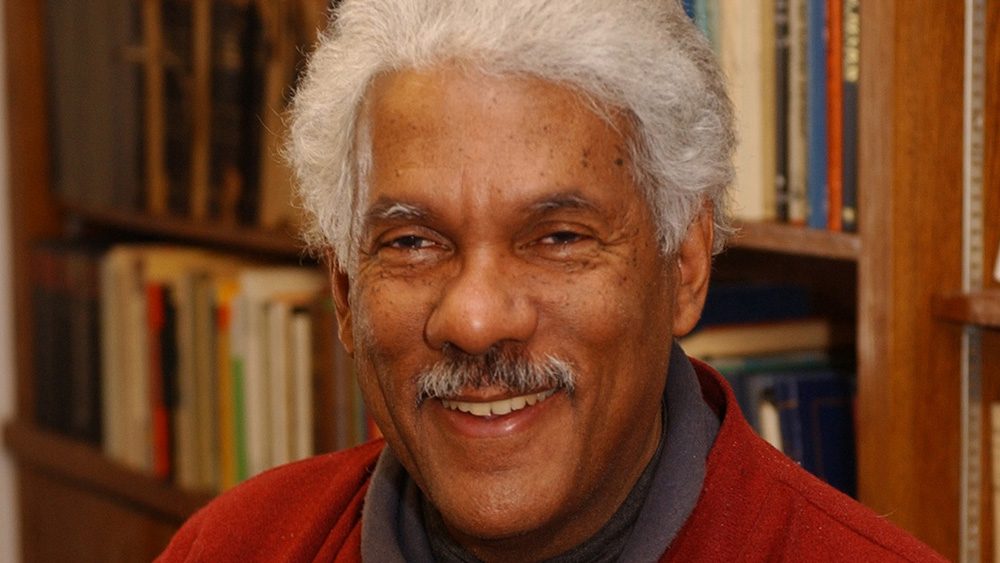

Late last year I was in New Jersey to film an interview with Albert J. Raboteau – an African-American professor of religion at Princeton University. The interview was for the Centre for Public Christianity’s documentary For the Love of God: How the Church Is Better and Worse than You Ever Imagined, part of a segment on Christian-inspired non-violent protest in the Civil Rights movement in the United States.

I’d interviewed about 40 scholars and writers and experts of various kinds for this project. They were all fascinating people. But none of those conversations stuck in my mind quite like this one. Raboteau is not only an academic expert in the religious experience of African-Americans but his life has been defined by prejudice and racism.

Three months before Raboteau was born, his father was shot and killed by a white man in Mississippi.

It is personal for him.

Three months before Raboteau was born, his father was shot and killed by a white man in Mississippi. That man was never even indicted for the killing after he claimed self-defence. Raboteau was raised by his mother and stepfather, who decided not to tell him about the circumstances of his father’s death until he was 17 and ready to go off to college.

“They sat me down and for the first time explained to me what had happened,” explains Raboteau. “The reason they didn’t tell me before was they didn’t want me to grow up hating white people.”

“There is a deep root … in the African-American community that has always appreciated that hate as a way of attacking hate is a no-win situation.” – Albert J. Raboteau

Raboteau says they were successful in that aim. “There is a deep root … in the African-American community that has always appreciated that hate as a way of attacking hate is a no-win situation,” he said. “Hate and even resentment, as [Martin Luther] King and others taught, leads to the corrosion of the individual person’s own humanity. It just doesn’t attack the other, it attacks and [affects] the individual.”

It was deeply moving to listen to this softly spoken professor, a man who radiated kindness and grace. Clearly the approach of Martin Luther King Jr and the leadership of the Civil Rights movement had enormously inspired him. That philosophy of non-violence was not only brilliantly effective as a political tool but remarkable in its counter-intuitive beauty; Raboteau has drawn strength from it.

King had become a somewhat reluctant leader of the Civil Rights movement in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955 where he was serving as a pastor at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. He was thrust into the limelight as a key spokesman in the Montgomery bus boycott, a successful year-long protest by African-Americans against racial segregation on public transport. Early in the boycott, King received a phone call at his house with the threat that it would be bombed and he and his family killed. This was a pivotal moment for King. In the interview, Raboteau described the moment:

He just sat down at the kitchen table with a cup of coffee and said a prayer, which basically was, “Lord, I’m down here trying to do good, but I’m losing my courage and I can’t let others see me losing my courage, because then they will lose their will to fight this fight.” He said he heard a voice speaking to him, saying, “Martin Luther King Jr, stand up for what’s right, stand up for justice, and I will never abandon you. I will never leave you. I’ll never leave you alone.”

For Martin Luther King Jr, non-violent resistance was not about passively submitting to an evil power but courageously confronting evil by the power of love.

For King, that kitchen table experience became for him the rock-solid basis for his activism even though he knew as his life went on that he was not going to die in bed. King’s resolve was tested just a few days later when his house was fire-bombed with his wife and baby daughter inside. They survived unhurt but it was a clear sign that the struggle ahead was going to be costly.

That night an angry mob of his supporters gathered on the front lawn of his house wanting to avenge the attack. King addressed the crowd – men armed with sticks and guns and shovels – and he pleaded with them to go home. He reminded them of Jesus’ words that “those who live by the sword, die by the sword.” Astonishingly, he called them to love their white brothers no matter what. They must meet hate with love.

For King, non-violent resistance was not about passively submitting to an evil power but courageously confronting evil by the power of love. It sought to provoke the perpetrators of injustice in order, ultimately, to seek reconciliation. “Non-violence is a powerful and just weapon,” wrote King. “It is a weapon unique in history, which cuts without wounding and ennobles the man who wields it. It is a sword that heals.”

When you consider the appalling injustice King’s people faced, the restraint they showed is truly extraordinary.

When you consider the appalling injustice King’s people faced, the restraint they showed is truly extraordinary. King viewed all this through the lens of the Christian gospel. For him it was the cross of Christ that is “the eternal expression of the length to which God will go in order to restore broken community. The resurrection is the symbol of God’s triumph over all the forces that seek to block community.”

Albert Raboteau had his own intensely spiritual moment that enabled him to let go of natural resentment. When he was 50 years old he returned to Mississippi and, after some investigations, located the son of the man who had killed his father. He asked him what his family’s memory of that incident was. The now middle-aged son of the killer explained that he remembered Raboteau’s father as a big, burly man who had fought with his father and in self-defence was shot and killed. Raboteau has a picture of his very slim, tiny-framed father who couldn’t possibly have been the threatening presence in this description.

Raboteau learned his father’s killer had eventually been diagnosed with terminal cancer, and had shot and killed himself. At the point of being able to inflict pain on another, he chose mercy.

During the conversation Raboteau learned his father’s killer had eventually been diagnosed with terminal cancer, and had shot and killed himself. Raboteau was tempted to ask if the same gun was used as the one that killed his father. But he recognised “that would have been cruel, so I didn’t.” At the point of being able to inflict pain on another, he chose mercy.

“After that conversation, I visited my father’s grave. I had been there many times over the years, but for the first time I began to cry. It was as if in my mind’s eye I saw him. I saw him being shot and I saw him falling. It was as if he was falling into my arms and into my life, and it was as if a father and son had finally met.”

Raboteau describes that as “a moment of peace … a moment of reconciliation that was deeply gratifying for me. It was as if some proper ending had been made.”

Why did this interview so affect me? I think it has to do with the concept of congruence – a life lived in harmony with the ideas we say we believe. In 2006, Professor Raboteau received the MLK Day Journey Award for Lifetime Service. In presenting him with the award, president of Princeton University Shirley M. Tilghman said: “Professor Raboteau is a source of inspiration for all who wish to build the kind of society that Dr King envisioned: a society in which the life of the mind and spirit propel us toward each other rather than apart, where suffering, if it must occur, is redemptive rather than destructive.”

Simon Smart is Executive Director of the Centre for Public Christianity.