If we were to take a pulse-check of the church in Australia today, what would we see? We would see that in many places in our nation, the church is held in disrepute as a place in which great evil was concealed and even permitted. We would see sections of that church known for exploiting people’s spiritual vulnerability. And behind it all, we would see a church wrestling over the issue of spiritual authority.

Is it a church which listens to its traditions, to its institutions, to religious experience, or to the Bible? While the massive gulf of five centuries separates us from the church of the Reformation, far more deeply embedded as it was in the culture and politics of its day, the questions of the church’s identity, mission and authority were as vital questions then as they are today.

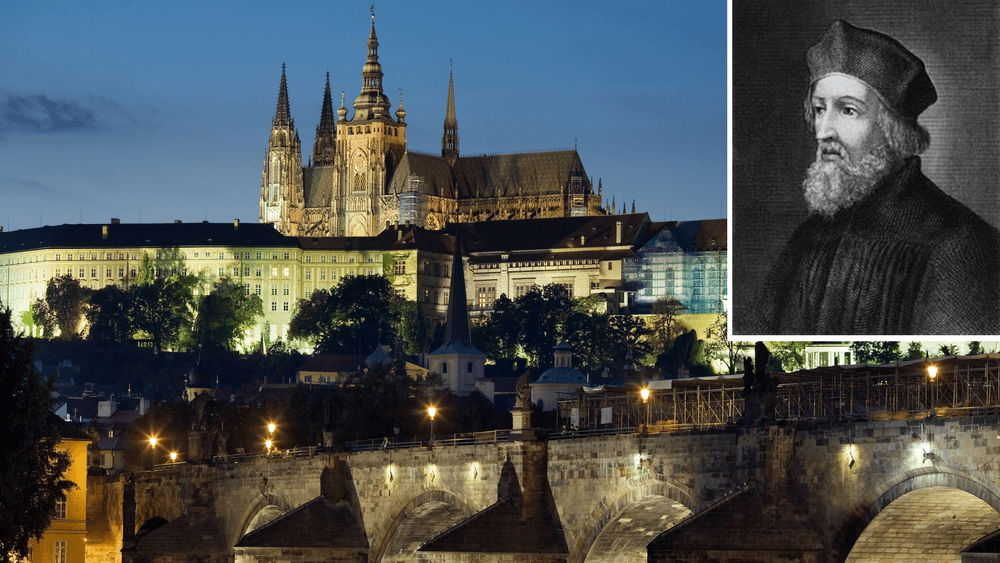

One hundred and two years before Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the church door in Wittenberg, Germany, a Czech preacher and theologian, Jan Hus, was burnt at the stake for heresy at the Council of Constance. His career was an inspiration to Luther, and, Luther also noted carefully, Hus’s fate. To challenge the authority of the medieval church was no small thing.

To tell the story of Jan Hus, we need to tell the story of the church of his day. It was governed, at least in theory, by the Pope in Rome, a single church under a single powerful head. Only, since 1309, the Pope wasn’t in Rome, he was living in Avignon in France. And then, in 1378, after an attempt to restore the papacy to Rome, there were two Popes elected to succeed Pope Gregory XI – which split Europe almost completely, because everyone chose to back one Pope or another.

In the Middle Ages, the Papacy was a bit like Google is now: it was just an unmistakeable part of life.

In 1409, a council held in Pisa in Italy tried to break the deadlock by electing yet another Pope. But since not everyone recognised this new Pope, there were now three Popes trying to preside over the Catholic Church!

It’s hard to understate the confusion and anxiety that this situation caused. In the Middle Ages, the Papacy was a bit like Google is now: it was just an unmistakeable part of life. To think that it was divided and possibly corrupt was a shock to the whole system and an embarrassment to faithful Christians everywhere. Could it be that the whole way the church had been organised was mistaken?

It’s not surprising that dissenting voices began to be heard, starting with the Englishman John Wyliffe. Wycliffe contrasted the church that he could see around him, which was wealthy, powerful and hierarchical, with the heavenly church which exists for all Christians. Wycliffe wrote powerfully that all the institutions and doctrine of the church should be tested at the bar of Scripture. He also attacked the traditional view of the Lord’s Supper, writing that the bread and wine were not changed into the body and blood of Jesus in the Eucharist but remain bread and wine.

A movement sprang up around him, called the Lollards, and a translation of the Bible into English followed. This mysterious movement included some of the gentry, apparently; but it was repeatedly suppressed in the turbulent years of civil war that followed Wycliffe’s death.

Nevertheless, Wycliffe had a surprising influence in a far-off place: in the kingdom of Bohemia, which we know now as the Czech Republic. His writings came to the notice of the Czech-speaking Dean of the Philosophy Faculty in Prague, Jan Hus, who was growing more and more cranky with the institutions of the church. There was already a bit of ill-feeling at the university between the Germans and Czechs. But more of that in a moment.

…his name was literally John Goose, which caused him and his friends quite a bit of amusement.

Hus was from a town called Husinec, or “Goosetown.” Like many people of the time, he was called by the town he came from – so his name was literally John Goose, which caused him and his friends quite a bit of amusement.

Hus had studied to be a priest not because he was overcome by spiritual fervour but because he wanted a way out of poverty. He was ordained in 1401 and became the preacher in the Bethlehem Chapel in Prague, which was a very large and well attended centre of faith. Sermons there were preached in Czech and not in Latin! And already it was known for the rebellious attitude of the Czech leaders towards the established church.

During this period, Hus experienced a conversion of a kind. It was a discovery of the Scriptures, at the prompting of Wycliffe, that moved Hus to be alarmed at what he saw were the unbiblical practices of the church of his day. One of his colleagues, Matthew of Janov, once said that the clergy were “worldly, proud, mercenary, pleasure-loving, and hypocritical. … They do not regard their sins as such, do not allow themselves to be reproved, and persecute the saintly preachers. There is no doubt that if Jesus lived among such people, they would be the first to put him to death.”

This was fighting talk. But Hus and the others were protected because they had a strong advocate in King Wenceslas IV and Zybněk Zajic, the young reform-minded archbishop of Prague. They wanted the Czech nation to be free of European and especially German control. The appeal for reform sounded well to them.

Many of Wycliffe’s teachings sounded pretty good to Hus, from his reading of the Scriptures. For example, he began to teach that the true church was all of those whom God had chosen for salvation, and was not the same as the Roman Catholic Church. Wycliffe had also taught that there should be “territorial churches, each protected, regulated, and supported by the territorial lords and princes” rather than one large institution. Hus did not agree with Wycliffe on the Lord’s Supper, but did not condemn him.

And this became significant, because the Germans at the university organised a push to get rid of the Czechs. They drew up 45 points from Wycliffe’s writings, and condemned them as heresy. Either you agreed with them, or you couldn’t teach at the university anymore.

Then, in all the confusion surrounding the three popes, Archbishop Zybněk decided that he could not cover Hus anymore, and excommunicated him. Worse was to come, because King Wenceslas wanted to profit from the sale of indulgences. Indulgences were a way of buying merit from the church – so that you could effectively purchase your way to the kingdom of heaven. Hus angrily protested against this as a “traffick in sacred things.” But he lost the protection of his king as a result.

A church needs to submit to the Scriptures, the book of Jesus himself, or it is no church at all.

Don’t forget, we have the problem of the three popes going on as well at this time. To resolve the mess, the Council of Constance was formed in 1414 – with a brief to rid the church of heresy, too.

Jan Hus was invited to attend, with a guarantee of safe-conduct from the Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund. Would he go? Hus hesitated, but was reassured that all would be well. It wasn’t. Once he arrived at Constance, Hus was imprisoned and then interrogated at length. The conditions of the prison were so bad that he nearly died. A public hearing was set for June 5-8 of 1415, but Hus was not given permission to respond. His accusers presented him with a list of 30 articles – a mish-mash of his writings and Wycliffe’s. If he would not renounce them, then he would be condemned.

Hus replied that unless someone could show him from Scripture where he was in error, he would not recant.

His final opportunity to recant came on July 6. He refused, and so was declared to be an arch-heretic and a Wycliffite. His soul was handed over to the devil.

He was then taken outside the city walls and burned to death. As he died, the story goes that he committed his own soul to God by singing: “Jesus Christ! The Son of the living God! Have mercy upon me.” After he had died, his ashes were scattered in the Rhine River.

That was not the end of the story, because a Hussite church grew up and flourished in the Czech lands for many years afterwards. And when the Reformation took place in the 1500s, the Reformers looked back to Hus with admiration at the stand he had taken on the authority of Scripture, at great cost.

That is the great testimony of Jan Hus for today’s church. A church needs to submit to the Scriptures, the book of Jesus himself, or it is no church at all. It needs to humbly give itself to be reformed by what it reads there. It should not be satisfied to do what an institution or a tradition tells it, but must inquire of the Bible to know what it should look like. The Bible creates the church, after all, not the other way around. Let not Jan Hus, and so many others like him, have died in vain!