When Harriet Beecher Stowe published Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1852, it sent shockwaves through American society. The best-selling novel of the 19th century gave many people their first real view of the institution of chattel slavery and the day-to-day horrors of the life of an enslaved person in America’s south.

Lincoln called it “the book that caused the Civil War.” It was a powerful vehicle to create empathy for a whole class of people who had been abandoned to the vagaries of brute market economics. Stowe claimed that the book came to her through a series of visions and that it was literally inspired by God.

Those engaged in the battle to end modern slavery may feel the need for an equally dramatic moment of divine intervention.

Late last year, barely noticed amid the infighting of the Liberal Party, Australia’s first federal Modern Slavery Act (MSA) was passed with bipartisan support. The MSA introduces mandatory reporting for large corporations with annual global revenue above $100 million. These entities will be required to publish annual statements on their actions to address modern slavery in their supply chains and operations. The hope is that the reporting will mean modern slavery risks will be considered at the highest levels within the largest businesses in the Australian market.

It’s a start.

Modern slavery is a huge contemporary problem most of us would prefer to ignore – so remote as it appears to be from our everyday experience. The International Labour Organisation and Walk Free Foundation estimate that 40.3 million people are held in slavery today. That’s more than at any other time in history. About 24.9 million of that group are victims of forced labour slavery, where they are coerced, underpaid or unpaid, and where, under threat of violence, workers are compelled to stay in their roles where conditions are often abusive and unsafe. The horror stories are many and varied.

And modern slavery is closer to home than we like to think. About half the world’s slaves are in our Asia-Pacific region and many are buried in an ecosystem of goods and services we end up accessing through grocery stores and clothing outlets. Think surf wear produced in North Korean sweatshops or prawns for your weekend barbecue being brought to you by trafficked fishermen on Thai trawlers. Walk Free Foundation estimates that $12 billion worth of goods and services come to us each year via the misery of an abused and exploited underclass.

The parallels with the 18th- and 19th-century abolitionist movement in the US, and its precursor in the UK, are not hard to find. Slavery at that time was a foundational and essential part of the economic prosperity of both Britain and America.

“Econocide” was a term used to describe what people thought would be the impact of losing what most considered to be a necessary, if unpleasant, part of their nation’s economic success.

The defeat of modern slavery is equally urgent.

Victory for the abolitionist cause required then, as it does today, more than legislation. People’s hearts and consciences had to be captivated. William Wilberforce, the English politician who doggedly and repeatedly brought anti-slavery legislation before the parliament, his friend and fellow campaigner Grenville Sharpe, and indeed Harriet Beecher Stowe across the Atlantic, were all driven by the fundamental belief that every person, regardless of status, capacity or rank, was made in the image of God and therefore of inestimable value. It was a powerful basis, with a long history, on which to inspire a movement. It’s true that the Bible was used, perversely, to support the institution of slavery. It was also essential in its eventual demise.

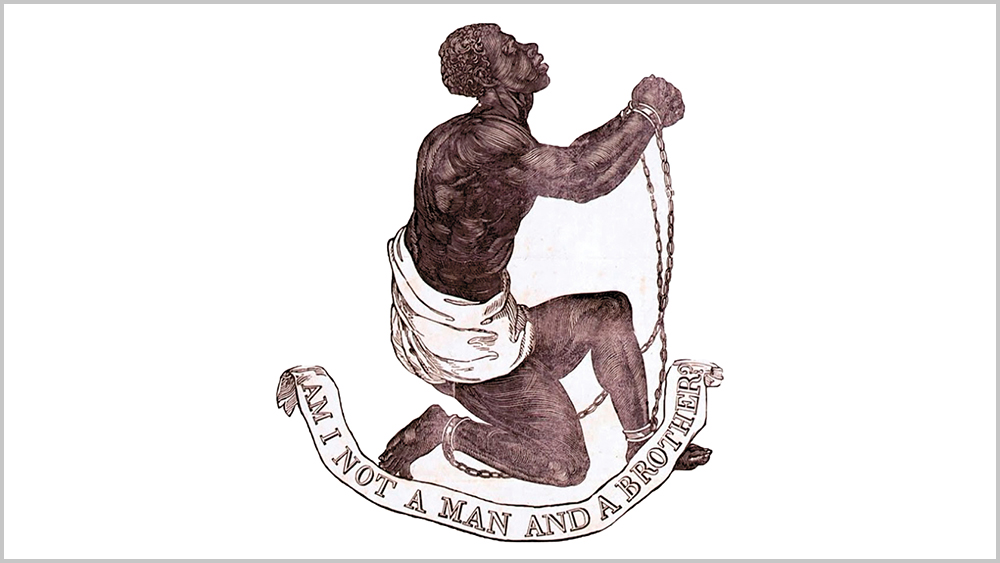

In the 1780s, Josiah Wedgwood, the manufacturer of bone china, and friend of Wilberforce, released what would become a well-known image featuring the profile of an African slave in chains. Inscribed around him was a question: “Am I not a man and a brother?” There was also a female equivalent with a woman asking: “Am I not a woman and a sister?” The brilliant simplicity of this morally freighted question demanded a response. The image became widely recognised as it was incorporated into plates, jugs, tea caddies, bracelets and hairpins.

In the 1790s, about 300,000 people (mostly women) boycotted sugar grown on slave plantations, reducing sales by up to a half. The boycotts – a precursor to the contemporary fair-trade movement – were repeated in the 1820s and ’30s. These were important steps and signs of a growing recognition that any purchase we make contains an ethical dimension. It didn’t make economic sense to end the slave trade in the 19th century. But, when it became clear the whole institution was morally unsustainable, it couldn’t last.

Only when a compelling vision of human dignity took precedence over economic expediency did the institution begin to unravel.

The defeat of modern slavery is equally urgent. The suffering, humiliation and brutality contained within it are immense, as is the task of dismantling its foundations. Governments and legislation can help. Essential, though, is a widely held attitude that recognises our obligation to the powerless and oppressed, and a belief that, yes, we are “our brother’s keeper,” even and especially when it costs us something. That means a willingness to forgo a bargain for ourselves that in truth is costing someone else a great deal. Only time will tell if we still have the moral imagination and commitment to do what it takes to overcome a modern stain that, shamefully, touches us all.

Simon Smart is the Executive Director of the Centre for Public Christianity and co-presenter of the documentary For the Love of God: How the church is better and worse than you ever imagined.