The Bible and the bullet

Under intense bombardment at Gallipoli, Lance Corporal Elvas Jenkins was struck directly over his heart by a lead ball from an exploding shell. He would have died instantly but the ball struck his New Testament which he carried in his shirt pocket. The Bible saved his life that day. But he did not survive the war. Among the first Anzacs to reach Gallipoli on Anzac Day, 25th April 1915, he was also one of the last to leave. He was among those who survived the whole of the Gallipoli campaign, only to lay down his life a few months later on the Western Front in France.

Elvas Jenkins was the kind of decent and courageous young man whom Australia will remember forever. His “Bible with the bullet” ended up with his fiancée, Jeanie. Now, nearly a century later, her descendants have donated it to the Bible Society’s collection of historic Bibles.

This is Elvas Jenkins’ story and the story of his Bible.

Elvas Jenkins: saved from a shell explosion in Gallipoli by his French New Testament

Elvas Elliott Jenkins was born in 1888 at Ararat in country Victoria, the eldest of seven children, all with the same middle name. When Elvas was twelve, the Jenkins family moved to the Melbourne suburb of Ivanhoe where he attended the Fairfield State School. He was a popular boy, described as “sturdy, high-spirited, fond of fun, full of mischief, unselfish, good-tempered and reliable”.

In Ivanhoe, Elvas became an enthusiastic member of the local Methodist church. There at a ‘Decision Day Service’, the young teenage boy “gave himself to the Lord Jesus”, a decision that would influence the course of his young life, and even the nature of his death.

Elvas quickly became thoroughly involved as one of the leading young people in the life of his church, teaching Sunday School and becoming secretary of the local YPSCE (‘Christian Endeavour’). After a few years he became a local preacher.

In 1903 Elvas left school at 15 to take up an apprenticeship with a Melbourne printing firm, McCarron Bird and Co. He was good at his job and well-liked by his work mates, but in the end, it was not enough for Elvas. In 1910, at the age of 22, he left the printing trade to train for the Methodist ministry.

Elvas entered Queen’s College at the University of Melbourne to study theology. It was almost certainly there at the University that he met Jeanie Reid, who was studying medicine. What is far less certain is how much Elvas’s family knew of Jeanie, but her descendants still treasure the love letters he wrote from the battlefront. Elvas and Jeanie had a special understanding. Officially or unofficially, she was his fiancée. They were in love and they planned a future together.

Elvas completed his studies in the middle of 1914 and was ordained into the Methodist ministry. A month later, in August 1914, Britain declared war on Germany. Almost immediately, like so many other young Australians, Elvas volunteered for military service. His official date of enlistment is 17th September 1914. He was placed in the 2nd Field Company Australian Engineers as a sapper (Private), part of the first AIF (then called the Australian Infantry Expeditionary Force).

On 7th May, a shell landed and exploded where Elvas and his men were working. Elvas was struck directly over his heart. A lead shrapnel bullet struck the middle of the book, passing through the Psalms and Revelation and piercing the pages all the way to Acts. Beyond Acts, the Gospel pages stopped the bullet.

In his enlistment papers, Elvas is described as having average height and build, fair hair, brown eyes and a bronzed complexion. He left Melbourne for the war in the first convoy of AIF troops on the transport ship Orvieto on 21st October. A little over a month later they arrived at Alexandria in Egypt where the Australian troops were gathering and training ahead of active deployment to the battlefield. The 2nd Field Engineers were sent to Mena Camp.

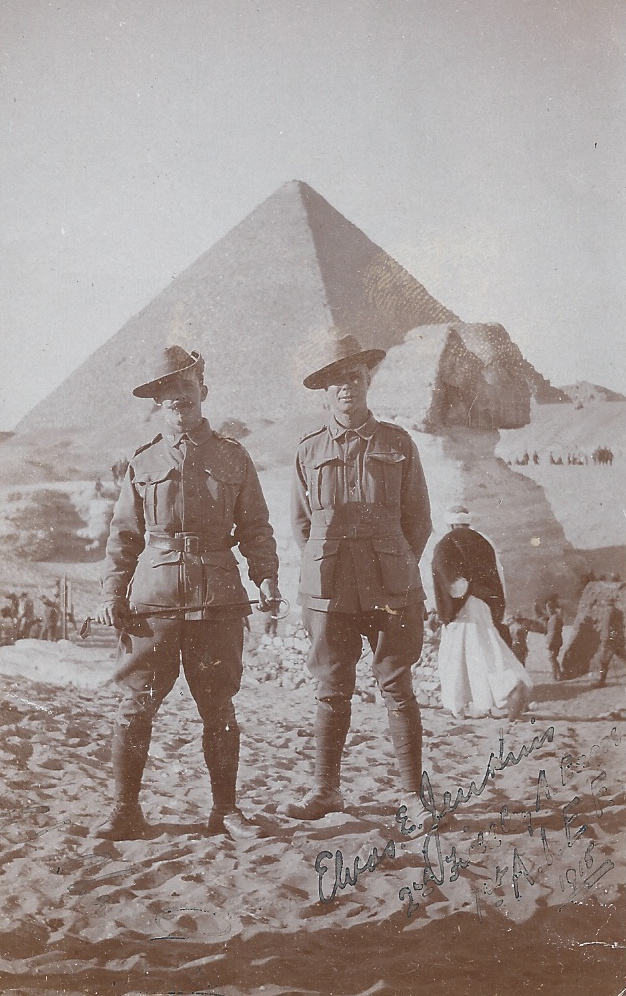

Elvas Jenkins in Egypt

It was in Alexandria that Elvas obtained the New Testament that he carried to Gallipoli. Curiously, it was a French New Testament. It is uncertain exactly how he got it. There was a substantial French quarter in Alexandria and indeed French is still one of the languages spoken there today. Given Elvas’s Christian background and his theological interests, it is hardly strange that his souvenir of Alexandria would be a Bible.

But it is a very particular Bible. It is the 1901 edition of the 1894 revision of the Ostervald translation of the New Testament, an important French Protestant edition published in 1774. An intriguing possibility is that one Sunday Elvas, as usual, sought out a Christian church in Alexandria, and found a French Protestant Church. That may be how he procured his little French New Testament and Psalms. The inscription in the front reads, ‘Elvas E Jenkins, Mena Camp, Egypt, 1914. 1st A.I.E.F.’

After 3 months training, Elvas was promoted to Lance Corporal just a few days before his unit was deployed to Gallipoli in April 1915. Australian and New Zealand forces began landing at Gallipoli at 4.30 a.m. on Anzac Day, 25th April. By 7.00 a.m. Elvas’s 2nd Field Company Australian Engineers had landed and quickly set about their assigned tasks, unloading guns and ammunition, constructing a pier, sinking wells to assure water supply, constructing trenches and tunnels and dragging artillery up to the battle lines. Lance Corporal Elvas Jenkins was in charge of one of these groups and, as usual, carried his French New Testament in his shirt pocket, over his heart.

The Turkish Army was shelling the Anzacs with German-made Krupp 75mm field guns, firing shells packed with explosives and shrapnel bullets consisting of lead balls of calibre 295 x 10g. The shells exploded on impact, spraying the shrapnel bullets in all directions. On 7th May, a shell landed and exploded where Elvas and his men were working.

Elvas was struck directly over his heart. He was carrying his French New Testament and Psalms back-to-front in his pocket. A lead shrapnel bullet struck the middle of the book, passing through the Psalms and Revelation and piercing the pages all the way to Acts. Beyond Acts, the Gospel pages stopped the bullet. They are compressed but not pierced through. The lead ball still sits there today. In the back of his Bible, Elvas later wrote, ‘Shrapnel bullet from shell of 75mm field gun. About May 6 or 7, 1915’.

His life spared, Elvas fought on at Gallipoli, doing his job well and was promoted to Corporal, then Sergeant. The Anzac evacuation was finally ordered in December 1915. Among the last few to leave, Elvas stepped ashore back at Alexandria on 27th December, where the exhausted Australian and New Zealand soldiers rested and recuperated. On 10th March, Elvas was transferred to the frontline engineers, the 1st Pioneer Battalion, and immediately commissioned as 2nd Lieutenant.

The Anzacs were sent to join the BEF (British Expeditionary Forces) fighting in France on the crucial Western Front. Elvas’s 1st Pioneer Battalion arrived in Marseilles on 2nd April where Elvas was one of the men granted leave until the Pioneer Battalion’s role was determined. He formally rejoined his Battalion on 2nd June and on 22nd June was promoted to full Lieutenant.

The Anzacs were assigned to the Battle of the Somme to attack and take the strong German entrenchment in and around the village of Pozières. The role of the 1st Pioneer Battalion, as its name indicates, was as an advance party, going ahead of the main attacking force to prepare the way, dig trenches, set up barricades, and, if the situation demanded, to repel the enemy themselves. It was an extremely dangerous assignment.

The real attack on the German stronghold in Pozières was scheduled for 23rd July. The 1st Pioneer Battalion was sent on ahead a week before with new Lieutenant Elvas Jenkins leading a group who were to establish a forward position very close to the German lines.

Historian Charles Bean wrote that the Pozières ridge “is more densely sown with Australian sacrifice than any other place on earth”.

On 19th July, Elvas was in charge of a reconnaissance party determining the precise location of the German trenches. They were in extreme danger. A deeply committed Christian, Elvas briefly led his men in prayer, unaware that he was in the sights of a concealed German sniper. Elvas was shot and severely wounded. Taken to a Field Ambulance (mobile medical unit), he died the next day. His record tersely notes – ‘G.S.W neck and chest. Died of wounds’. He was among the first Australians to lay down his life in the Battle of the Somme.

Elvas was the first Australian to die in the Battle of the Somme.

The Anzacs eventually did take Pozières from the Germans but at a frightful cost. Historian Charles Bean wrote that the Pozières ridge “is more densely sown with Australian sacrifice than any other place on earth”.

Elvas’s service records show that he was ‘buried at Fricourt, 3 miles east of Albert, France’. Eventually, the British established an official cemetery at what they called ‘Dantzig Alley’, the nickname of a large German trench near the village of Mametz. Bodies that had been hastily buried elsewhere were reburied there. Elvas was among them and his body still lies there today.

When Elvas had first arrived in Egypt he had been required to write a will. Leaving almost everything to his brothers, he made a very specific bequest of personal items to Jeanie Lawson Reid, whose address he provided. This included his books.

The military authorities kept strictly to the terms of his will. His effects such as clothing were parcelled up and sent to his brothers, who eventually received his medals too. But his French New Testament was a book, and so the authorities sent a little package to Jeanie.

Jeanie grieved for Elvas for a long time. Ten years later, she married another wounded war veteran, Albert Jeays. Theirs was a happy marriage, but Jeanie’s love for Elvas was no secret to the family. Jeanie treasured the little French New Testament, his photos and the letters he wrote from the war. Her family has lovingly preserved Elvas’s memory ever since. It is through the Jeays family that the Bible Society has finally become the custodian of the ‘Bible with the bullet’.

The donation was the direct result of the society’s display of historic Bibles in Brisbane. John Harris had given a lecture at the exhibition and he was approached afterwards by the husband of Jeanie’s great niece.

At his memorial service in August 1916, they said they had worked with him for many years and that “we have but one opinion of him: he was one of the best”.

John eventually located and contacted the Jenkins family. They too had kept alive the memory of their great uncle Elvas. In 1975, his brother Spencer had donated two stained glass windows in his memory which were installed in the chapel of Queen’s College. Here, a memorial plaque has long listed Elvas with all those from the College who gave their lives in the war.

It seems, however, that the Jenkins family knew nothing of the ‘Bible with the bullet’. This is not surprising: soldiers did not write home about injuries and near-escapes. Elvas’s family may have had no contact with Jeanie at all nor known at the time that she had received a package from the military. So two separate families kept his memory alive. But only now can Elvas’s story be put together.

Like so many others, Elvas is an Australian hero who gave his life for family, friends and country. He was a deeply committed Christian. We can let his work mates from the printery have the last word. At his memorial service in August 1916, they said they had worked with him for many years and that “we have but one opinion of him: he was one of the best”.