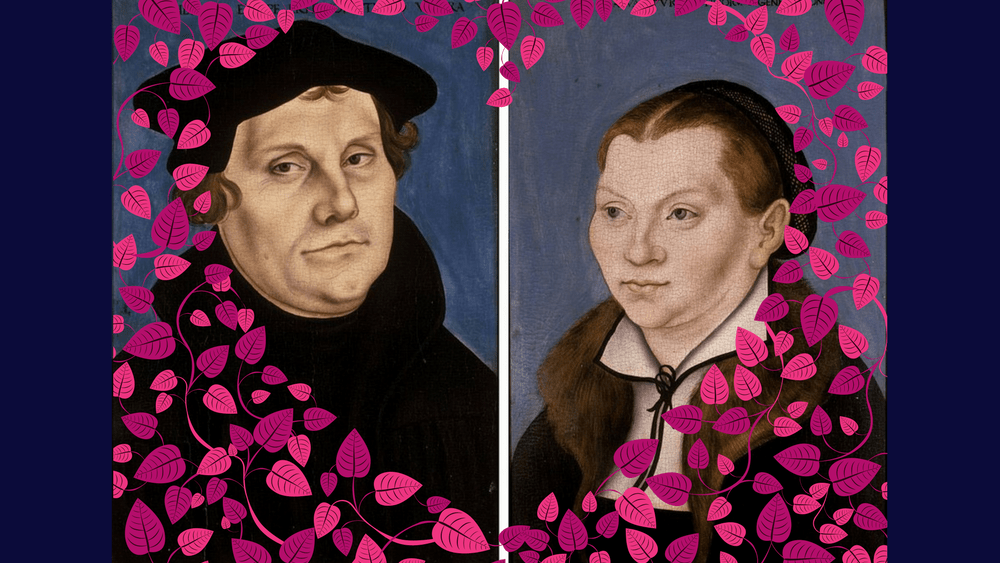

The Bachelorette of Wittenberg

How one woman won the heart of a confirmed bachelor

She was a proud and feisty nun. He was a renegade monk and confirmed bachelor. But when Martin Luther helped the remarkable Katharina von Bora and eight other Cistercian nuns flee from their convent in secrecy, he was on the path to another reformation few people know about.

On this 500th anniversary of the Reformation it is worth re-telling the dramatic story of how, on Easter Eve 1523, Luther sent a merchant who regularly delivered fish to the Mariathron Convent to help the aristocratic nuns escape in some fish barrels in his covered wagon.

[Luther] truly believed it was wrong for women to be pressured into making a vow of singleness.

This brave abduction proved to be game-changing to the progress of the Reformation. Luther rescued and took in the nuns – which was a crime under canon law, punishable by death – not because he was seeking a wife but because he truly believed it was wrong for women to be pressured into making a vow of singleness, as many nuns then were.

The daughter of a poor nobleman, Katharina had no choice in becoming a nun. She was sent to a convent at the age of five and took her nun’s vows at 16. But when she and her fellow nuns caught wind of Luther’s liberating writings she contacted him secretly urging him to help them escape to promote the cause of the Reformation. Luther was writing things such as “your vow is contrary to God and has no validity” – don’t delay but “get married.”

Luther asked the women’s parents and relatives to take in the refugees, and when they refused he set about arranging marriages or employment for the runaways – and succeeded with all but Katharina.

In 1525, the former monk and former nun married – the same day as he proposed.

Luther was determined to help Katharina find a husband and tried to set her up with a professor colleague in his 60s. Feisty Katharina made it plain that she was not interested.

She confided in Nikolaus von Amsdorf, a friend of Martin’s and a fellow Protestant reformer, that she would be willing to marry only Martin or himself.

For a year Luther grappled with the idea of marrying Katharina (a bit longer than the two months contestants on The Bachelorette get). Close friend Philipp Melanchthon advised against it, believing a scandalous marriage to a refugee from a nunnery might damage the young Reformation cause, but Luther’s father was enthusiastic and encouraged him.

Katharina considered her marriage an assignment from God.

Eventually Luther decided his marriage “would please his father, rile the Pope, cause the angels to laugh and the devils to weep.” In 1525, the former monk and former nun married – the same day as he proposed. She was 26; he was 42.

While Katharina did not marry for love, by all accounts they had a warm and affectionate marriage. Having converted at the age of 24, Katharina considered her marriage an assignment from God. (We doubt the contestants on The Bachelorette think the same). Living in a former dormitory for friars in Wittenberg, Luther devoted himself to scholarship while Katharina ran a farm and brewery, raised cattle, fed the students who lived with the family, gave birth to six children, and ran a hospital. Luther called his wife “the boss of Zulsdorf” (the name of their farm) and “the morning star of Wittenberg” for her habit of rising before the dawn to meet her many responsibilities. She called him “Sir Doctor” even after their marriage – not something today’s Bachelorettes would countenance!

Luther discovered that in a good marriage husbands actually need to take their wives’ wishes into account.

Like many couples, they fought over finances and aristocratic Katharina tried to “civilise” Luther, who came from peasant stock. Luther jokingly called Katharina “lord,” having discovered that in a good marriage husbands actually need to take their wives’ wishes into account. But he also called her “my sweetheart Kate.” He loved her resourcefulness, dedication to detail, and faithfulness to Christ. They were a great pastoral example for families in their day.

Luther respected Katharina and valued her opinion in a time when a woman’s voice was not heard. A woman known for her wisdom, she exercised incredible influence in shaping the Lutheran College that gradually grew around their home. She was once on a search committee to hire a new pastor, which was unheard of in those days.

Katharina’s role as the great reformer’s wife paralleled his marital teachings. Their marital strength set a good example for other Reformers and had a powerful and lasting effect on Renaissance culture and society. It brought about a reformation in the way people thought about marriage.

After Martin died in 1546, Katharina was heartbroken. With the outbreak of Black Plague, she fled to Torgau where she was seriously injured in an accident with her wagon and horses and died three months later in 1552. She was 53.

Beyond their unusual love story, the union of a monk and a nun ended the idea that clergy were to live celibately and thus changed the face of the church forever.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?