Jesus speaks my language, he’s not only the God of the white man

The history and ongoing power of the Wubuy Bible translation

By a campfire in a remote Aboriginal community in North Australia in 1945, the story of Jesus was read in the Wubuy language for the first time. This special moment has happened many times in the world when receptive people first hear the gospel in the language of their hearts. The power of that historic reading is still recalled by the descendants of those who were there.

By a campfire in a remote Aboriginal community in North Australia in 1945, the story of Jesus was read in the Wubuy language for the first time. This special moment has happened many times in the world when receptive people first hear the gospel in the language of their hearts. The power of that historic reading is still recalled by the descendants of those who were there.

At that isolated campfire, a group of tribal Aboriginal people heard the word of God and the impact is still felt today.

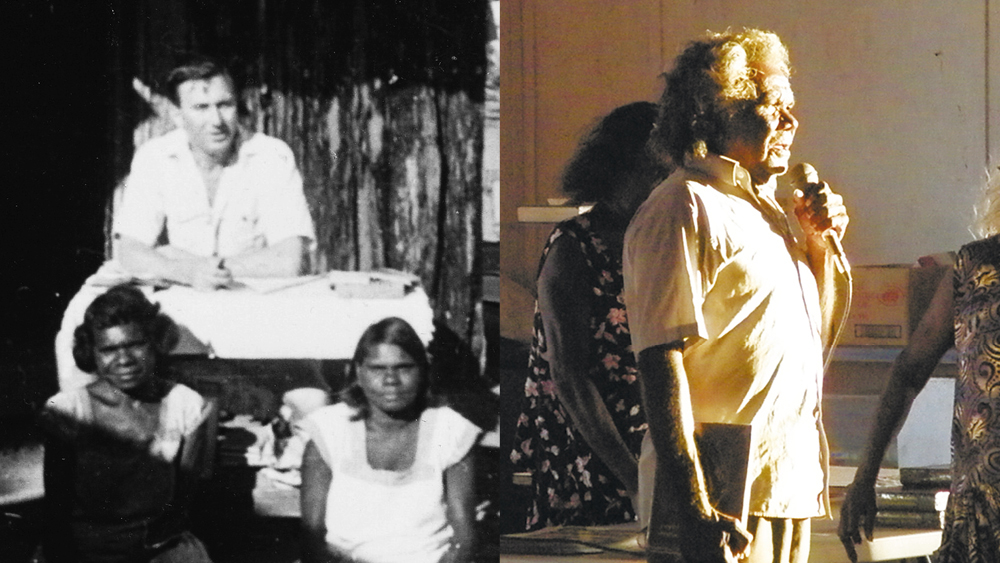

The reader was my father, Len Harris, a lone missionary in Arnhem Land during the dangerous years of World War II, when other missionaries had been evacuated south, away from the war zone. Len was chaplain to the Church Missionary Society missions in the Western Gulf at Roper River (Ngukurr), as well as at Groote Eylandt (Emerald River Mission). Len was a talented natural linguist with a flair for picking up languages.

Travelling between several Aboriginal communities, teaching, encouraging the small band of Christians and baptising new converts, Len was continually frustrated by the multiplicity of languages and the challenge of communicating the gospel.

Len realised one of the languages, Wubuy, was widely understood around the Arnhem Land coast because its speakers, the Nunggubuyu people, were great travellers by canoe or across country. It was a kind of “lingua franca” in those days, so Len decided that it would be the best language into which to translate the Bible.

He learned Wubuy as best he could and also began to write it down. Len determined to translate the Gospel of Mark into Wubuy and decided to do it at the Roper River Mission (now Ngukurr) where there were Nunggubuyu Christians. This is my father’s story.

“I asked the Nunggubuyu Christians to choose two translators, one who could speak English and one who could not. They chose two outstanding Christian women, Bidigainj, who knew no English, and Grace Yimambu.”

“Grace had been the best English speaker at a mission school but had gone to live in the bush with her husband, a good thing because it kept her Wubuy language skills strong too.

“Every day we sat under a tree outside my bark hut. I would explain the meaning of the words to Grace in English. Sometimes I tried my few halting words of Wubuy. Grace then explained the words to Bidigainj in Wubuy. Together they would make a Wubuy sentence. Then they repeated the sentence slowly to me and I wrote it down. I then read it back to them. The two women used to laugh at my pronunciation but I didn’t care at all. What we were doing interested me beyond anything I had ever done before. Never can I forget those first wonderful words: Anaambalaman ana-lhawu – the Good Story.

“Whenever we finished a story about Jesus, the two women got very excited. At night I would go down to the camp near the river to sit with the people and read them the new translation. They too were very excited, keenly discussing the stories and always insisting that I read them again and again.

“At the campfire one night, listening intently, was Bidigainj’s brother, Madi, a powerful Nunggubuyu elder. After the second reading he got up from the fire and left. No one knew why but he had set off to walk back to his own country, the Nunggubuyu heartland around Rose River, three hundred kilometres to the north. There Madi and other men made a little fleet of dug-out canoes and in them Madi brought 60 of his people back down the coast and up the Roper River. The journey took them two weeks, living on fish, turtles and water lilies.

What had convinced Madi that the life of Jesus was true?

“So it was that one night, as I was reading some of the last chapters of Mark’s Gospel by the campfire, that I glimpsed Madi in the firelight, standing just behind the eager listeners. I held up my handwritten sheets of paper.

“‘Anaambalaman ana-lhawu,’ I said. The Good Story. ‘Yuwai. Idjubulu,’ Madi replied. ‘Yes. It is true.’ Then 60 of his people emerged from the shadows to crowd around the fire. Madi had brought them to hear the good news of Jesus Christ in their own language. God’s Spirit felt close to us that evening. I read it and read it again, urged on by the listeners, over and over, long into the night. When at last my voice started to give out, they let me stop. Madi came forward and asked to hold in his hands the ‘leaves’ I had written on. I knew he could not read.

“‘Idjubulu,’ he said again. ‘It is true.’ He tried to speak but I did not understand. My Wubuy was not good enough for such deep thoughts. Madi signalled to Grace and Bidigainj to interpret for him. Through them he told me that he once used to think Jesus was the God only of the white man but that now he understood that Jesus was also the God of the black man.

“I asked him which stories had impressed him; what had convinced him that the life of Jesus was true. He looked down at the sheets of paper and looked up at me again, his eyes bright in the firelight.

“‘It’s not the stories,’ he said. ‘It’s the words. Now I know that Jesus speaks Wubuy.’”

An important spin-off from Bible translation is language preservation.

The Gospel of Mark and the Epistle of James were published by the New South Wales Auxiliary of the British and Foreign Bible Society in 1948.

In 1952, Madi’s dream of a Christian community in Nunggubuyu lands began to be fulfilled with the establishment of the Numbulwar Mission on the Rose River. In 1961, the Church of the Holy Spirit was dedicated. Many of the descendants of Madi and the people who first heard the gospel in the Wubuy language are active participants in the life of the Church of the Holy Spirit and continue to witness for Christ in the Numbulwar community today. Never did they lose the dream of the Bible in their own language. Largely unaided, they struggled to translate it over many years. Few remain alive who remember my father, but 65 years later the Wubuy New Testament was dedicated in the Nunggubuyu lands in 2010.

An important spin-off from Bible translation is language preservation. The Wubuy language is threatened – but the existence of the Wubuy New Testament and part of the Old Testament will pay a key role in that language’s future. Wubuy is not only being threatened by English but by the spread of Kriol, which is the first language of younger people at Numbulwar (Wubuy remains their second language).

The Wubuy New Testament is now extremely important for language preservation. It is a solid volume in the traditional Wubuy language and is the model for now, and the future, of how Wubuy is spoken.

Together with the grammars and word lists, the Wubuy Scriptures provide an invaluable resource for language preservation and renewal.