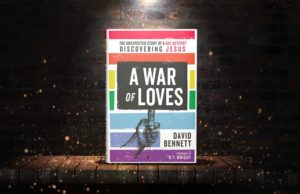

David Bennett is a frequent Eternity contributor. We have previously shared the story of how he went from an atheist gay-rights activist to a celibate Christian man, and more recently spoke to David about the challenges and joys he faces in following Jesus. Here, in an extract from his new book ‘A War of Loves’, David tells the story of his early days, when he struggled with his sexuality and the response from the church.

You, Lord, brought me up from the realm of the dead; you spared me from going down to the pit. —Psalm 30:3

‘Praying for gay celibacy’ could be banned

Same-sex attracted Christians are called to a life of love, not just self-denial

I'm a same-sex attracted Christian

A ‘gay agnostic’ and a Christian chat candidly about same-sex marriage

It was the first Friday evening since moving to the Sydney harbourside, and a day after my fourteenth birthday. From a high sandstone outcrop bordering the water, I watched the sun set over a small mooring of boats. The chiming of their sails rang out from the cove and over the peninsula. A blush of ochre tinted the sky. Sydney Harbour Bridge was hidden behind the eucalyptus trees, but the cityscape was in view on the horizon, iridescent with skyscrapers. Such beauty made me ache for someone to share it with – another young man. Standing in my untucked school uniform, I peered over the ledge, where water lapped at oyster-laden rocks down below. The ferry glided on the incoming tide with its monotone growl. Tears welled up from what I knew was true. I feel light enough to jump over the edge. The crushing ocean seemed lighter than my unwanted desires, and my feet dared me to step over the edge of the cliff. I pulled back in sudden horror. My heart raced as I ran home and the dusk fell.

The search

I often heard strange terms used to describe homosexuality. Either it was a kind of spiritual oppression that needed to be prayed away, or it was a result of sexual abuse that required serious healing. None of these pseudotheories fit me.

Not long after, I found myself at school. The recess bell rang throughout the school grounds, and the summer sun shone over the brick buildings. More than 1000 boys, each in the traditional uniform of red-lined navy blazers, white shirt, grey woollen trousers, black shoes and a navy blue tie, poured through the grounds to the entrances of the Anglican chapel. It was a chaotic sight that somehow always managed to become orderly in minutes as everyone lined up to enter. We resembled an army regiment at attention, with just a few naughty soldiers out of formation.

Soon the sound of hundreds of adolescent boys singing awkwardly from hymnbooks filled the chapel. As I took my place among the pews, my vision blurred. I had fond memories of singing solos in the boys’ choir before my voice broke, and of my favorite soprano solo: Howard Goodall’s The Lord Is My Shepherd. But today I was silent, repulsed by the thought of singing to a God I knew didn’t exist, since his only response to my unspoken questions had been a deafening silence. My hardworking agnostic parents had attained an upper middle class lifestyle. Life was good, but I was often unhappy and lonely, surrounded by the boredom and beauty of the suburbs. I dreamed about escaping to the city, which offered the liberty and sophistication I craved. Our extended family had a wide range of religious beliefs and convictions. With my Christian relatives, I often heard strange terms used to describe homosexuality. Either it was a kind of spiritual oppression that needed to be prayed away, or it was a result of sexual abuse that required serious healing. None of these pseudotheories fit me.

All I wanted was a place where I could be honest.

For other Christians, homosexuality was the worst of sins and homosexuals were God’s enemies. This rhetoric missed the reality of what I was going through and closed me down to the honest confession and self-acceptance I deeply desired ever since I awoke at the onset of puberty to my attraction to men. The widely variant views of why people are homosexual – genetics? abuse? father issues? something else entirely? – bombarded me. I felt so confused.

On top of this, coming to terms with my attractions at the age of fourteen meant entering an ugly, polarised culture war that spanned the globe. All I wanted was a place where I could be honest. All I wanted was to find a boyfriend and escape the monotony and ignorance I perceived in the people around me. Then I could finally be accepted and move on with my life.

One night I cried out, “Take these attractions away!” Nothing changed, and the silence drove me farther away from Christianity. The attractions I’d felt since age nine weren’t about a lifestyle I’d chosen. They were about who I was. Since a young age, I’d understood that a person’s romantic attractions shape their humanity. Love makes us human, and without it, life is not worth living. I wanted all that life had to offer, so I knew I had to keep my distance from those Christians who were getting in my way. Still, the message that God didn’t approve of people like me gnawed at my conscience.

For a year, I tried to think of the opposite sex the way my peers did. Then I dismissed such thoughts as ridiculous. I didn’t believe in God, so why worry anymore? My growing interest in men’s bodies had only increased, and the nervousness I experienced around certain members of the same sex brought me to a place where I knew I was attracted exclusively to men. I even wrote a poetry anthology about my inner secret.

The belief that we’re all born this way wasn’t the whole story.

As the chapel service ended, I concluded I could no longer put off the reality of my attractions. The more I denied them, the more miserable I became.

Searching through science

Why was I gay? Shows like Queer as Folk or Will and Grace simply told me I was made or born this way. That wasn’t particularly specific. I began searching for an answer. I read through nature versus nurture arguments in studies. I googled everything I could find.

Simon LeVay’s research in 1991 showed there was a substantial difference between the brains of gay and straight men in the hypothalamus. Other studies found that gay men responded to the pheromones of men, not women. Studies on identical twins showed a genetic contribution to sexual orientation, but not a genetic determination. More recent studies had shown the potential influence of the hormonal environment of the womb. Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic theory for homosexual behavior linked same-sex attraction to parental relationships. Environment? Biology? Genetics? Nurture? Hormones? Conditioning? Nothing was conclusive. Little was clear or known about the why of it. And that almost crushed me. Understanding myself seemed completely out of reach.

A war developed in me about how to understand this part of my identity. The belief that we’re all born this way wasn’t the whole story. I was more confused than ever.

This is an excerpt from David Bennett’s new book ‘A War of Loves’, which is published this month by Zondervan.