A day in the life of a hospital chaplain

The intense but scattered conversations of a typical day of chaplaincy

We spend a day on the wards with Rev Stuart Adamson, one of ten accredited chaplains of different faiths and denominations at Prince of Wales and Randwick Hospitals Campus in Sydney. He is one of three Anglican chaplains and has a twin role as a chaplain and a trainer of chaplains at Anglicare.

I’m usually up before my alarm. But I am on after hours on-call at the moment and when the alarm goes off at 6.45 am I feel pinned to the bed. The call-out last night wasn’t all that late, but it was just as I was going to bed. A social worker at emergency called me because a lady in her 90s had just died and the daughter asked for someone to come and pray with her.

I live nearby so it doesn’t take me long to get there. When I go into the room there are two women and three police officers around the bed asking questions, trying to work out if the woman’s death needs to be referred to the coroner’s office. The police kindly leave the room when I arrive.

When the alarm goes off at 6.45 am I feel pinned to the bed. The call-out last night wasn’t all that late, but it was just as I was going to bed.

The daughter and her friend are a little bit anxious, so I let them talk things out. The daughter tells me her mum stopped going to church years ago due to infirmity and the fact that she could no longer hear the sermons. “But she would want you here,” she said. I wonder how many others have had her experience. We talk for a time, and pray. But it is not time to get into a long conversation. It is 10.45 pm, ED [Emergency Department] is buzzing and the police need to ask more questions.

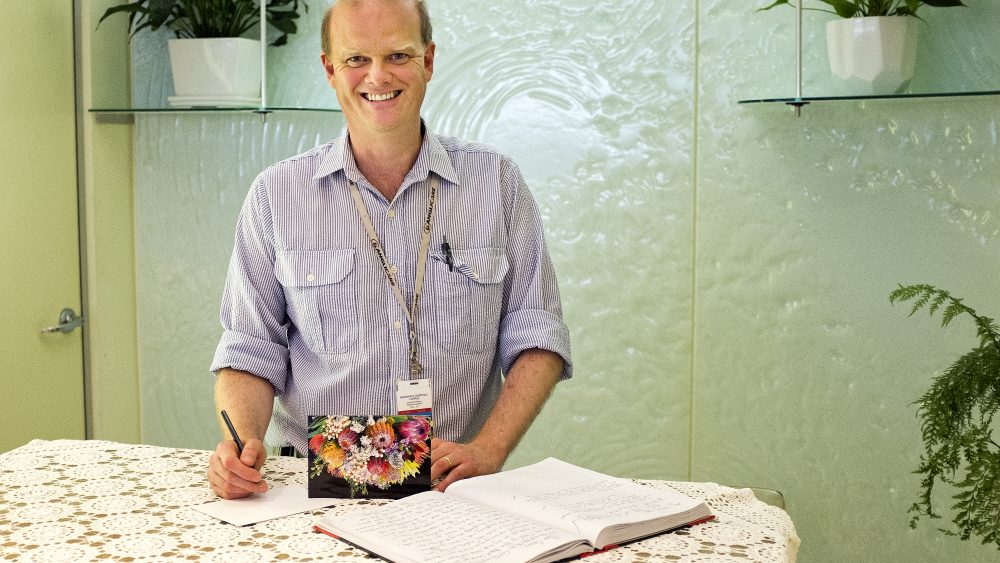

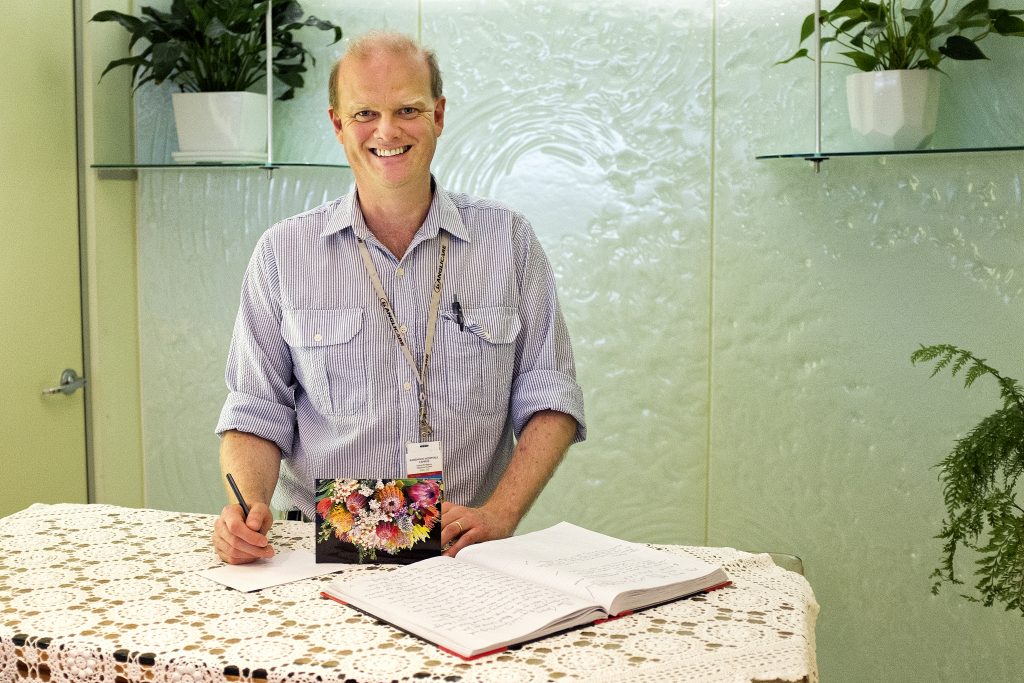

Stuart Adamson in the chapel at Prince of Wales Hospital. Anne Lim

In the morning I reach the hospital about 7.45 am, a bit earlier than usual. I start by going into the chapel near the foyer, which is open to all the faiths. Muslims use it for daily prayer, Jews use it for festivals, Catholics and Anglicans for services and prayer. There’s a book with hundreds of prayers in it written by patients and staff. Chaplains come here regularly, read the prayers and pray for the people who have written in it. Today there is a beautiful prayer from a woman thanking Jesus for creating “a whole new reality” in her life “free from regret.”

Then it’s time to sign into the office. I print the patient lists and look over them, spotting new critical patients, patients who have been in for a while and patients in wards that may not have been visited recently.

Today there is a beautiful prayer from a woman thanking Jesus for creating “a whole new reality” in her life “free from regret.”

Then it’s 30 minutes of chat, coffee and prayer with the volunteers. Normally we have five or six “vollies”, who have all been trained through our Anglicare chaplaincy courses, but today we only have two, Rossie and Louise. After praying that the Holy Spirit would go before us today, I give them the lists of patients who have said on admission they would be happy to be visited, and tick those to follow up.

We’re blessed that the hospital views chaplaincy as a key part of holistic care and recognises research that indicates patients who receive pastoral and spiritual care are more likely to get well and go home sooner.

All of us are trained to engage sensitively with people who may not identify with any particular faith.

The chaplaincy department rightly recognises that while we may all be human, each chaplain of each faith needs to have the freedom to operate out of their particular faith tradition. While we work together really well, we have clearly defined chaplaincy groups. So if during discussion with a patient I realise they identify with a different faith group, then I’ll make a referral. As other chaplains would for me. At the same time, all of us are trained to engage sensitively with people who may not identify with any particular faith.

Today my first visit is to Gary in the renal ward. He is a bit of a frequent flier. He’s in a good mood, and is making jokes, but we’ve had some rough times over the past six or so years. He’s a diabetic and in that time he’s had two leg amputations, several strokes, had a stent put in his heart and he’s just been diagnosed with Parkinson’s. He’s been in just about every ward in this place and had a number of close shaves, but he came to faith in the rehab ward about four years ago. We’ve had a lot of conversations and read about half of Mark’s Gospel together. He really loved it and engaged with it thoughtfully with all his life experience, though not a great deal of education behind him. Last year we thought he wouldn’t see his first granddaughter born and he was really down, but he’s in a different place now.

He is a bit of a frequent flier. He’s in a good mood, and is making jokes, but we’ve had some rough times over the past six or so years.

“I don’t like the situation but I’m coping now, thanks to divine intervention,” he says in his soft but laboured voice.

Gary, left, came to faith four years ago while in a rehab ward. Anne Lim

“Before I was plodding along and I didn’t have much hope. Now I wake up in the morning and it’s a new day and I know everything is going to be all right.

“My granddaughter is the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen. She’s even better looking than I was. She’s starting to say a few words – mum, dad. She doesn’t say poppa yet but that will come,” he says with a grin.

I always try to fly under the radar, rather than be obvious in a collar.

I recently discovered that Gary lives not too far from me, so I worked out a day I could take him to his local church and now a bunch of guys turn up every second Sunday and roll him off there in his wheelchair. It makes my heart sing because chaplains are at a different coalface but we have to have active partnerships with churches. It has been an absolute joy to introduce Gary to his local and for them to pick up the ball.

Today Gary is eager to tell me what he has learnt from studying Mark’s Gospel at church, and comparing King Jesus and King Herod. God teaches me much through Gary.

“I was at the pokies and the next minute – boom!” he says. “I was dead.”

By the time I get to the coronary care unit, the hospital is buzzing with nurses, doctors and other staff going everywhere. A kind of organised chaos. I always try to fly under the radar, rather than be obvious in a collar.

I catch up with Geoffrey, who is having a pacemaker put in. An elderly man with the remnants of a Gloucestershire accent, he loves a chat and hates being interrupted.

“I was at the pokies and the next minute – boom!” he says. “I was dead. I’ve lost two days of my life and I can’t remember a thing!

“Look at that sun. Please, God, don’t take me away today. Take me tomorrow if it’s a nasty day.”

Geoffrey had a heart attack while playing the pokies. Anne Lim

At my next stop I visit a woman in her early 50s who is in pain from a pinched nerve in her spine and hasn’t slept well. She is distressed because the doctors don’t know what’s wrong and she is happy for me to pray with her.

I’ve learnt that if I try to anticipate the action of the Spirit, things all go pear-shaped, so I roll with it and trust God.

Prince of Wales is a big teaching hospital and specialises in cardiac treatment, so patients often come from far away and are in for a while. We sometimes get a referral from clergy in a regional town asking us to visit someone from the parish. They are often glad of a visit and to be reminded that people love them and are praying for them and caring for loved ones in their absence.

I’ve learnt that if I try to anticipate the action of the Spirit, things all go pear-shaped, so I roll with it and trust God. It’s been a scrappy morning, but that’s how it usually is. I go back to the office to debrief the vollies and to check on follow-ups.

Early afternoon is rest time for patients, so I tend to do quiet, unobtrusive visits on wards that are dark. Sometimes people are bored and you can have nice, quiet conversations in whispers. Sometimes I’ll catch up with a staff member. I bump into people as I go along and a chance meeting with someone who is going through a difficult time can end up being a really significant conversation.

He seems a little nonplussed that I should care enough to visit.

This afternoon I go on to ICU and follow up on two patients I haven’t had the chance to see earlier. I talk with one husband about powerlessness in the face of his wife’s illness and another patient about a hip operation.

I take a detour to the annexe (a secure ward where patients are transferred from Long Bay Jail for a particular medical issue). I spend time with a guy who is getting out in the next few months and suggest he touch base with my chaplain colleague down at the jail, so he can set himself up for some good decisions once he gets out rather than slip back into old ways. He seems a little nonplussed that I should care enough to visit, and the two other inmates on the ward laugh and joke that the chaplain has come because things are worse than he thought. The warder and I say, almost in unison, “Well, we all gotta go someday.” They fall silent and look at each other, nervously. The warder adds, “It’s just a matter of when!” I wish I had a chance to talk to him too, but after praying with the patient, I have to go.

I have a few pastoral conversations with members of a staff prayer group, seeing how they’re going.

I follow up on a lady with multiple infections who has refused more treatment. She is tired. She has been by herself all day because her daughter is sick. I stay a short time, then pray, thanking God that even though she and her daughter couldn’t be together, their heavenly Father has promised that he will never leave or forsake them and that their names are “written in the book of life because they trust in Jesus.” Short, sweet and to the point.

Later in the afternoon I attend a lovely farewell for one of the social workers (the one who paged me last night), which provides an opportunity for ministry. I have a few pastoral conversations with members of a staff prayer group, seeing how they’re going. One says she is fine. I catch a flicker of sadness in her eyes and say, “Really?” She explains that she is tired. It would be good to catch up with her later for coffee.

He seems both sad and philosophical as he opens his heart to me.

As I head back to the office, venturing outside into the crisp air, I see a gaunt man about my age with three days of stubble sitting on the pavement in front of the psychiatric emergency care centre, his IV stand next to him like a ball and chain. He is doing his best to bask in a small patch of late afternoon sunlight, and he’s eating an ice-block. That gives me a clue as to why he’s in hospital. I inquire, and have hit the mark. That’s all the connection we need. I sit down next to him and stick out my hand. “Stuart. Chaplain.” His hand meets mine and he tells me his name. He talks for ten minutes about some people in his family who have cancer, about his partner’s mental illness and her refusal to seek help because she doesn’t want to be seen as weak, about his anguish as he considers how best to help her. He seems both sad and philosophical as he opens his heart to me.

Our paths have crossed for just a short while, but he was grateful to … share even the tiniest fragment of his burden.

As he finishes talking, I feel myself getting cold. I notice the patch of sun has gone and he is wearing light clothing. “Good to meet you. We better move on; it’s getting cold,” I say. “Yeah, I will. Good to meet you too,” he says. “Thanks for listening.” Our paths have crossed for just a short while, but he was grateful to have been able to tell someone what was on his heart, to share even the tiniest fragment of his burden.

It is after 6pm when I make my way home and, as I reflect on the day, I am struck by what a wonderful mutual blessing that last little chat was. Thank you, Lord. I must follow him up next week.

Pray

Some prayer points to help

- Please pray that Stuart and the other chaplains at Prince of Wales will have good conversations with the patients and staff that point them to the true source of hope and comfort.