Bronson Blessington ambles into the visitors’ room of the South Coast Correctional Centre in Nowra, NSW, his head lowered shyly on stooping shoulders. The prisoner’s bulky frame fills up his XXL white boilersuit, which is padlocked at the nape of his neck. As he tentatively approaches me, I’m struck by his open countenance, his clear blue eyes and ruddy cheeks.

He looks surprisingly young for a man of 47 who has been in jail for the past 31 years.

From Christian to Hindu and back again – a beautiful journey

The day Justin stopped running

How God snatched an ice addict from hell

I busted up our marriage and God fixed it

As Blessington perches self-consciously on a small stool bolted to the floor, he is gentle and respectful, asking questions about my trip from Sydney. It’s hard to comprehend that I am talking to a man who was convicted of a crime so heinous, so appalling to the public imagination, that his sentencing judge urged that he “never be released”.

For Blessington, who has been a Christian since the age of 16, it’s like looking back at another person when he recalls how in 1988, at the age of just 14, he took part in the kidnapping, rape and callous murder of a young bank teller, Janine Balding.

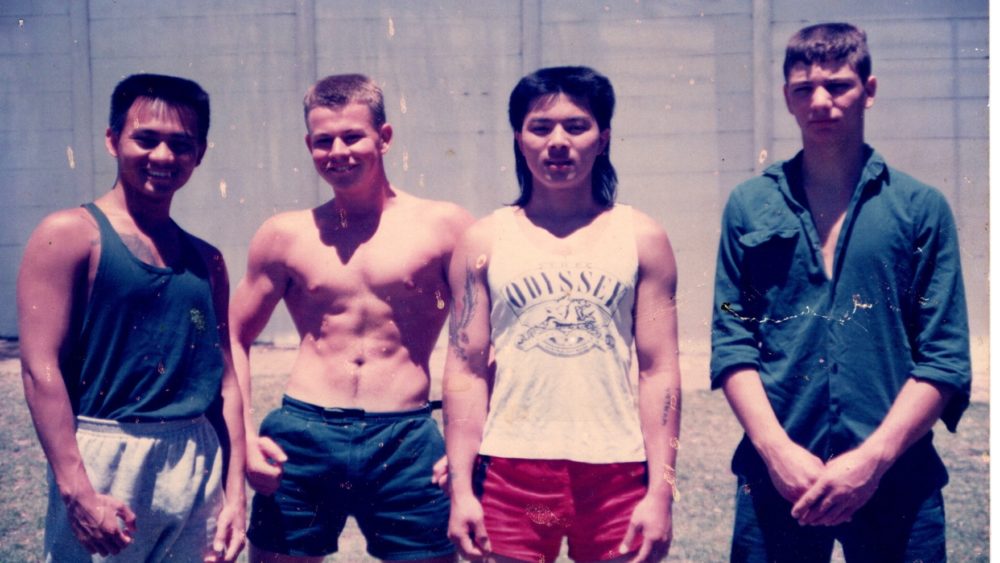

The last prison photo taken of Bronson Blessington before photographs were banned in the prison system

Blessington and one of his co-accused Matthew Elliot, then aged 16, received life sentences, but because they were still children, the law at the time offered a slim prospect of release in the distant future if they were considered rehabilitated. (Stephen Jamieson, 22 at the time, also received a life sentence.)

With the crime coming just two years after the horrific rape and murder of beauty queen Anita Cobby, the public outrage against Blessington and his cohorts prompted the NSW government to begin a “truth in sentencing” campaign. In 1997, 2001 and 2005, it passed three pieces of retrospective legislation that ensured they would, in the words of then Premier Bob Carr, remain “cemented in their cells” for the rest of their lives.

Imagine everything you have done over the past 31 years, if you have lived that long. Now imagine Blessington’s life, behind bars since childhood. He says it is like having been in a coma because he hasn’t seen anything of the world and its changes. He doesn’t even know how to operate a mobile phone.

When the teenage Blessington was first arrested, a female prison officer commented that he had the face of an angel, but in reality, his heart was a seething mass of anger, resentment, pain and fear.

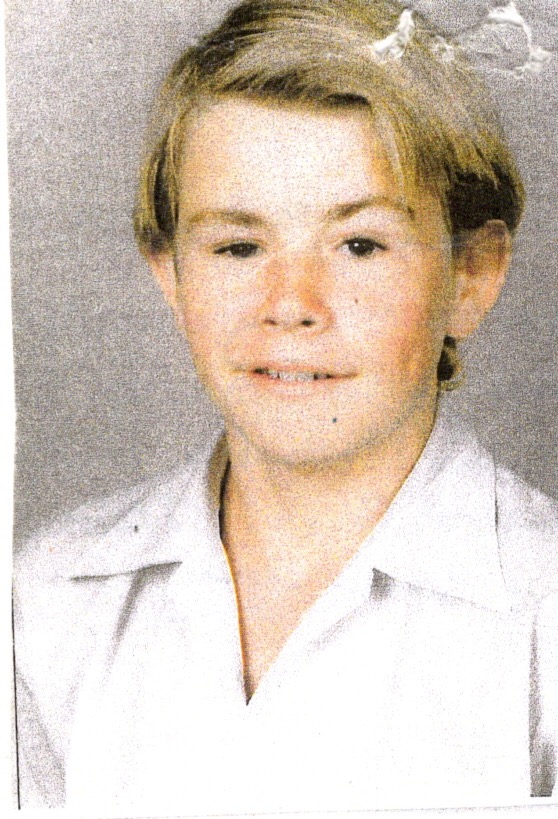

Bronson as a boy: abused and alone

He was just six years old when his parents, Barbara and Steve, split up. After the divorce, his mother was so poor that she cried all night when he came back from the shops having lost the change from a $10 note.

Blessington became obsessed with trying to get his parents back together and did all he could to disrupt a new relationship between his mother and a new “dad”. Exasperated, his mother dispatched him to live with his father, after which he spent a few years shuttling between the two parents.

“I thought my mum would be lonely, so I moved back with her. I thought my dad would be lonely, so I moved back with him,” he tells me.

It was while he was living with his father, who moved from caravan park to boarding house chasing work, that Blessington, frequently left alone, started to be sexually molested by four men, traumatic experiences that stoked his fear of adults.

“I lived in a fantasy world and that my sole object in life was to get my mum and dad back together.” – Bronson Blessington

By the age of 14, he was an alcoholic and petrol sniffer, truanting from school, getting into fights, stealing and, though illiterate, refusing to attend special needs classes. Finally, his dad and the school counsellors sent him for assessment to the Royal Far West Children’s Health Scheme at Manly, a charity designed to connect country children with developmental services.

“At this time, I was in a full stream of getting molested every day on a daily basis,” he says.

“I was going back and forth from parent to parent. I had gone to probably about 20 different schools at that time, so my mum had all the reports from the Children’s Health Scheme and they were tabled at court. The report stated I had the maturity of a nine-year-old at the time; I lived in a fantasy world and that my sole object in life was to get my mum and dad back together.

“While I was at the Health Scheme, I never made mention about the sexual abuse because I thought I’d be in trouble, so it was pretty difficult, you know.

“So you can see by this that my life leading up to the crimes against Miss Balding was devoid of anything worthwhile, you know? And if you don’t have the right people in your life, you’re going to turn to the wrong people and that’s exactly what happened.”

The ‘sledgehammer incident’

The story of what happened on that dreadful day in September 1988 has been retold many times. In brief, Blessington absconded with another boy from a boys’ home attached to Minda Remand Centre, Lidcombe, Sydney, where he had been sent because he was “uncontrollable”.

“There was a guy there – he used to get bashed by his parents real bad – and it was his birthday, so we went on an excursion and we both took off,” says Blessington. “Well, we met up with this group – we knew them for two days and then the sledgehammer incident happened.”

He’s referring to an “absolutely dreadful” attack on a boy called Wayne Purchase, after he and his friend teamed up with a bunch of hardened street kids at a homeless shelter at Central Station in Sydney. These included a 16-year-old with a long criminal history, Matthew Elliott, and 15-year-old Wayne Wilmot.

While demonstrating his agility with his fists, Blessington landed a punch full on the face on Purchase. The blood on Purchase’s face provoked Elliott, high on amphetamines, to slam Purchase with a hollow sledgehammer, urging Blessington to join him. The pair hit the boy with everything they had, leaving him half-dead.

“I went along with them because I had seen this guy’s head being belted in and I took part in it and I thought ‘If I don’t do what these blokes tell me, they’ll do that to me.’” – Bronson Blessington

Though Purchase survived, the incident rattled Blessington and his friend so much that his friend asked him to come with him the next day to a music shop.

“I didn’t understand at the time but, looking back, he was trying to get me away from this group. And if I knew [what would happen] I would have gone with him,” Blessington tells me.

“I was a scared kid and I went along with them because I had seen this guy’s head being belted in and I took part in it. I thought ‘if I don’t do what these blokes tell me, they’ll do that to me.’”

The attack on Janine Balding

Blessington remembers drinking a bottle of whisky the day the gang rode the train network, finally getting off at Sutherland station in Sydney’s south. He insists what happened next was not premeditated. It just unfolded with horribly tragic consequences. Contrary to a widely reported claim that Elliott and Wilmot had suggested, “how about we go and get a sheila and rape her?”, Blessington says the plan was to steal a car.

When Janine Balding, then engaged and a month short of her 21st birthday, neared her car, she was approached by the gang and Blessington asked her for a cigarette. When she refused, he pulled out a knife and forced her into the back seat. As she was driven in her Holden Gemini to the side of the road at Minchinbury in Sydney’s west, both Elliott and Blessington raped her at knife-point. She was dragged from her vehicle, gagged with a scarf, tied up, then lifted over a fence and carried into a paddock. Blessington held her down as Elliott punched her in the stomach while she drowned in a dam on the property.

At the time, Blessington couldn’t comprehend the enormity of his crime.

“When I was arrested, I said to the police ‘I’ll take you to the scene’ and they pulled me out of the car and we went throughout the trees and I see into the dam and I see a body floating. I couldn’t at the time reconcile myself as doing that,” he recalls.

“I was thinking ‘Far out, I’ve seen a dead body.’ I just couldn’t grasp it, you know what I mean? You see something on TV – and back then, you wouldn’t see dead bodies on TV – and my mind at the time was just scattered. Like, I just could not reconcile that I’d seen a dead body and that was all that was going through my mind.

“I was thinking ‘Far out, I’ve seen a dead body.’ I just couldn’t grasp it, you know what I mean? You see something on TV – and back then, you wouldn’t see dead bodies on TV – and my mind at the time was just scattered. Like, I just could not reconcile that I’d seen a dead body and that was all that was going through my mind.

“And over the years, when you do come to terms with it and you grow older and you mature, like, mate, I’ve been on my knees that many times bawling before the Lord over what happened and how much devastation I’ve caused the Balding family and people that they knew and things that may not happen now in the future, like children and grandchildren, and what my family has suffered. It’s just such a catastrophic domino effect.”

‘I pray for the family every single day’

At this point, you may be wondering what happened to change a boy who in his words was “a detriment to society” into a man supplicating humbly before God, fully repentant for the gravity of his sins and aware that he can never make amends.

According to Blessington, it’s the fruit of becoming a “new creation in Christ Jesus; the old has gone, the new has come.” (2 Cor 5:7)

“I’ve actually felt that and lived that. The old you dies, and the new you is being renewed; it’s growing in love and the Lord’s working in your life and he’s forgiven you of your sins. It doesn’t mean you’re going to stop sinning, but he’s working in your life to win back the strongholds that the Devil has to win back for his strongholds.”

“I could feed the world for a billion, trillion years and it wouldn’t do one thing to make amends.”– Bronson Blessington

Whenever Blessington compares his younger self to the man he is now, he sees two people and cries.

“I see that confused young fella that participated in that, and I do cry when I think of that; and I pray for the family every single day because I know that they are still suffering. I see it every time that I see them on TV. I know that their suffering is immense, and you can’t wrap your head around something so horrific like that.

“No matter how much you try, or you want to, make amends, I could never make amends. I could feed the world for a billion, trillion years and it wouldn’t do one thing to make amends.

“The only thing is the death of Christ and him loving that poor lost boy so much that he went to cross and he took that sin upon him … It’s something I think of every single day and I’ll never not think about it.

“I’ll never not feel remorseful; I’ll never not try and get better as a person because I’ve taken something that was precious to so many.”

‘I felt loved pretty much for the first time.’

Bronson’s life changed the day he attended a Bible study led by Jack Begnell, a Christian pastor from Cabramatta, who was unlike anyone Blessington had ever met before

“You’ve got to understand that Jack’s a real happy fella – I named him Happy Jack. He’s never down, he’s never sad … and he’s just an amazing person,” he says.

“Jack Begnell didn’t even know me, and he was telling me that he loved me and all these Christians were sharing their faith with me.”

Blessington, who had previously jeered at Christians, felt for the first time what it was like to love and be loved, and his life changed in a single moment.

“It was like my life at that time was like sadness and pain and a world of my own kind of thing and then it was like a star when it bursts into life.” – Bronson Blessington

“Around this time, I was getting a bit persecuted because of my size … there were a lot of things that were happening in my life at the time with my crime, and before all that when I was getting molested from a young age. I just seen that God had a purpose and a plan and with all the suffering in the world, there was just no hope in that, so I gave my life to the Lord and I just became real happy.

“It was like when you fall in love with someone. It was like that and I never felt any happiness like that in my whole life, so it was like a gravity was pulling me towards the Lord.

“My life at that time was, like, sadness and pain and a world of my own kind of thing – and then it was like a star when it bursts into life. And that’s exactly how it felt. I just felt happy, I felt loved pretty much for the first time. It was just amazing. All day long, before, I’d just dwell on the negative, and from that time on, I was thinking of heaven all the time, like every second of every day I was just thinking of the Lord. It was just amazing. It was the extreme of one end to the extreme of the other.”

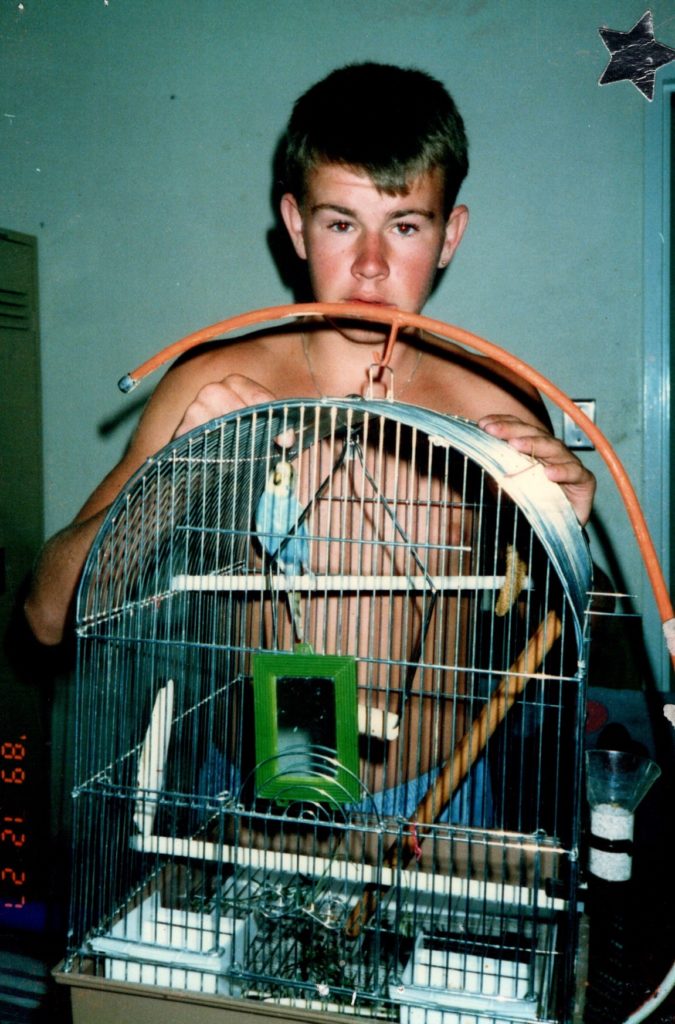

Bronson in Minda on December 27, 1989, a year and two months after his arrest

The afternoon he gave his life to Christ, Blessington went back to his cell and, in what can only be a miracle, found that he was able to read the Bible, albeit slowly. He began reading the Bible every day, memorising large chunks of the New Testament, especially the words of Paul, with whom he strongly identifies.

Singing praises to God in prison

Blessington says from the moment of his conversion he couldn’t stop talking about what God had done in his life.

“I was witnessing non-stop from the time I became a Christian. I prayed to the Lord to give me the power to witness and you couldn’t keep me quiet – I had to tell everyone,” he says.

“Well, after about three or four months, there were probably 10 to 15 of us from the one pod meeting in the kitchen and we’d be singing praises to God for about half an hour; we’d sing and clap and everyone had grins on their faces and we’d really want to hear the Word. It was the best thing that happened to us all week.

“There were different churches coming in. Jack would come in and some other church groups would come in, so we were going to church three times a week and the Lord did a mighty act there. Pretty much most of the jail was Christian or they wanted to know about Him. That was the first real work of the Spirit that I’ve ever seen like that.”

One night, after receiving his life sentence, Blessington was lying in his bed when he was visited by an extraordinary vision.

“I wake up and look at the end of my bed and I see two incredible dragon-like beings rolling around and they were fighting over me. One was a fluorescent red, and that was the bad one, and one was fluorescent yellow-and-orange and it was beautiful – and they were rolling around and they were fighting over me. And I saw it as God and Satan fighting over me, but it was probably two angels,” he says.

“I’ve experienced a lot of euphoric feelings because of drugs and it was just better than any drug you’ve ever felt in your life.” – Bronson Blessington

Terrified, Blessington got up, turned the light on and pressed the alarm to go to the toilet.

“I’m sitting in the toilet thinking ‘what has just happened?’ I went back to my slot and I turned the light off and jumped into bed and I heard a voice say, ‘Get up and read and pray’, so I got up, turned the light on and I started reading the Bible and I prayed; then I turned the light back off and jumped back into bed. Now I hear a voice as clear as day – because I was still petrified – and the voice said, ‘roll on to your side, my son.’ So, I rolled on to my side and I fell asleep – I had the best night’s sleep I’ve ever had in my life.”

The next morning, he couldn’t believe how tranquil he felt in his soul.

“It was just amazing. I’ve experienced a lot of euphoric feelings because of drugs and it was just better than any drug you’ve ever felt in your life. It was incredible – it was amazing; just lots of love and happiness and joy.”

Good news bears fruit in the Devil’s playground

From that time on, Blessington followed his deep desire to preach the good news inside the jail, and even developed a hope that, one day, he might help young people in the outside world avoid the mistakes he has made.

“In all my years, I’ve taken 2,500-plus Bible studies standing in the prison yards. That’s not counting all the Bible studies when I’ve just grabbed people and we’ve gone into a cell and we’ve had a Bible study,” he says.

The jails where he experienced the most gospel fruit were also the most violent – Goulburn in southwest NSW and Parklea in northwest Sydney, he says.

“In Goulburn, there were a lot of murderers down there and I’d hold the Bible up in the yard and call out ‘Bible study!’ to these guys – and I was in the most violent yard. And there’s no chance I’ve got that kind of courage! It comes from God, you know?”

While incarcerated at Parklea, “I was really on fire for the Lord and I really believe in seasons, like the Lord brings you into a season and you’re praying with all your heart for two or three hours a day, you’re reading like 10, 20, 30 chapters a day, you’re singing praises to him. I was praying that much I had calluses on my knees at this stage at Parklea. And people were just coming up and saying, ‘Oh, mate, how do I get into the Bible?’ And so you talk to them and over a period of about six months, probably about 40-something people gave their lives to the Lord.

“I had a really close brother there and we bought a packet of biscuits, a packet of lollies, a thing of cordial and some peanuts. On Christmas Day we invited every single person in the wing to come along to a sermon. Anyway, there was 45 people and we were preaching about the death of Jesus, even though it was Christmas Day – I think that’s the greatest gift that the world has received.

“Well, people were walking away with pocketfuls of lollies and biscuits and bottles of cordial. Later on that day … I noticed that where we had eaten outside and where I preached, sparrows were eating the crumbs from the biscuits … things like that, you just know that God’s real. I could not have done anything on my own in regard to my own courage or my own strength.

“Just to see God’s hand move in a place like this – this is the Devil’s playground. It’s a spiritual intensive care ward and people are coming here to learn about crime and evil and then they’re going out into the community and becoming urban terrorists.”

‘Without him I wouldn’t be where I am today’

One of the many men he has helped to rescue from a dark path in jail is Mitch Dundon.

“He tried to show me a better way and the time we spent together in prison really done that for me, you know? He showed me a better life and now I’m on a really good path and I’m with a really good church, Salt Church, in Port Macquarie,” says Dundon.

“Without him I wouldn’t be where I am today … He’s just a wonderful person and just the little words that he’d send down, like he’d see me in the yard and I’d have something on my mind and he’d go and pray for me. And I’d feel that prayer from the other side of the yard without even knowing that he’s praying for me, but you could just tell.”

Over the many long years that Blessington has been ministering to his fellow inmates, he has also developed friendships with some amazing Christians on the outside, notably Simon Manchester, former senior minister at St Thomas’ Anglican Church, North Sydney, who sent him books to develop his faith.

“The Lord, in his wisdom and mercy, has seen fit to save him and to begin to use him, so I have to bow my head at that point and say, ‘Well, you know, why should I condemn him if the Lord has not condemned him?” Manchester says.

Another friend is Neil Holman, who met Blessington while teaching guitar at Minda Detention Centre, when Blessington was 16.

“Bronson was the most ‘on fire’ Christian I had ever met, says Holman. “The first thing he ever said to me was, ‘Are you a Christian?’ His enthusiasm for Jesus was beyond anything I had experienced before, or since and it made such an impression on me, that we’re still friends 30 years later.

“I spent 30 to 45 minutes with Bronson in Minda every week for about a year before he turned 18 and was moved to the adult prison system. He spoke of Jesus a lot and shared a lot of Bible verses. He did most of the talking and ministering, despite me being seven years older.”

“He’s always encouraged me in the faith, and I feel has given me far more than I can offer him.” – Neil Holman

Holman says that conversations in subsequent years were always selfless and focused on others.

“He’s always encouraged me in the faith, and I feel has given me far more than I can offer him. His knowledge of the Scriptures and his prayer life are beyond mine, despite me growing up in the church.

“In his phone calls and letters, Bronson’s default is to encourage and build me up. It is rare for him to self-pity or ask for something other than prayer and most of those prayer requests would be for his inmates or sick friends and relatives.”

Still behind bars

In 2015, Blessington applied for clemency under the NSW governor’s royal prerogative of mercy – his last avenue to end his indefinite incarceration, which was found by the United Nations to be “cruel, inhuman and degrading” because of his juvenile status and a failure to consider his prospects for rehabilitation.

Five years on, the petition reportedly remains on the desk of the NSW Attorney-General.

Supporters, such as Holman and former prison chaplain Andy Thomas, believe it is time to balance justice with mercy.

“I believe it was just and fair for Bronson to go to prison for a lengthy period,” says Holman. “His crime was evil and cruel. He took part in the rape and murder of a precious, beautiful and innocent young woman. It permanently broke Mrs Balding’s heart. I met Beverley on two occasions. She was very gracious to me, but the impact on her was clearly devastating. The loss to Janine’s family and friends is immeasurable.

“In my view, by the 10-year mark, Bronson was well and truly ‘corrected’ and NSW correctional facilities should have been proud of their achievement.” – Neil Holman

“For the crime, damage done to her family and friends, protection for vulnerable people in our society, and a warning to others who might contemplate such crimes, a lengthy punishment was just and fair. Bronson would agree with this.

“I also believe it would have been just and fair for Bronson to have been released after 14 to 20 years. Even the sentencing judge acknowledged that given Bronson’s age, he had good prospects for rehabilitation.

“During a visit around the 10-year mark, I remember saying to my wife that any extra time Bronson spends in prison now is a waste. In my view, by the 10-year mark, Bronson was well and truly ‘corrected’ and NSW correctional facilities should have been proud of their achievement.

“A 31-year sentence (so far), for a 14-year-old, is infinitely inconsistent with comparable sentences. It’s more than double the penalty received by most of NSW adult murderers.

“Adult men get half this for killing the wives they’ve pledged to love, cherish and protect. How does that compare to a 14-year-old street kid from a dysfunctional family and under pressure from older boys getting a life sentence?

“Given Bronson’s remorse, rehabilitation and time served, I believe it’s just and fair that Bronson be released.”

Cancer and not letting anyone down

Although he has already served the equivalent of two murder sentences, the only circumstance that would permit Bronson’s release into the community would be if he were dying or incapacitated to the point that he could not commit a crime.

In a final phone call, Blessington reminds me that Australia is the only country that allows life sentences to be imposed on juveniles. Even the US Supreme Court ruled, in 2012, that mandatory life sentences without parole violated the Eighth Amendment. In 2014, the United Nations found that the sentences on Blessington and Elliott were in breach of Australia’s human rights obligations and asked that the situation be reviewed. The NSW government rejected this request.

Blessington has many friends who stand ready to help him assimilate back into society and whom he is adamant he would never let down by reoffending.

“The Lord has given me some wonderful people, like real heroes of the faith that, if I let down, I’ll be so ashamed,” he says.

“It just shows you that if someone puts up their hand for Christ and they give all of themselves to him to do as he wills in their lives, he can do anything. He can open any door, he can work so powerfully through anyone, even someone like me that had no education, that was like the pits of all society, and someone that just did not deserve anything, any chance at all, and he still loves me. And that’s amazing and how can I let him down like that?”

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?