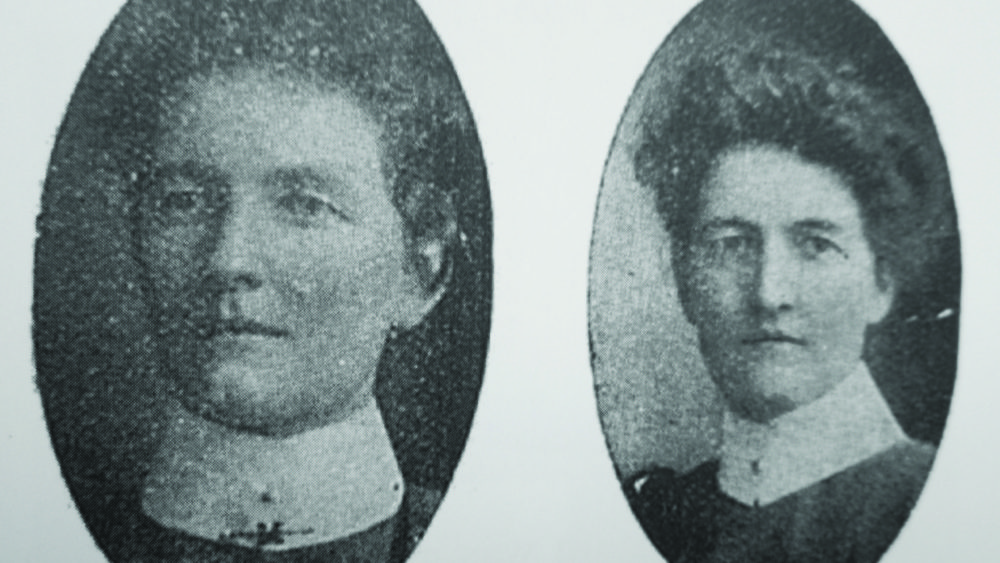

Through the Valley of the Shadow is a new book by Linda and Robert Banks, and tells the stories of five Australian women missionaries who served in China during periods of armed conflict. Working in villages, hospitals, schools, a university, orphanage and refugee centres, they suffered deprivations, hardships and dangers alongside the people among whom they worked. Here is an excerpt about twin sisters from Melbourne, Eliza and Martha Clark.

In mid-1937 Japanese forces for the first time crossed the border from Manchuria which, in the following months, escalated into full-scale war with China. In August, the first decisive conflict was the Battle of Shanghai in adjacent Kiangsu Province. This began with air raids, followed by naval bombardment, military invasion and finally street-to-street fighting which lasted until November.

“The two Miss Clarks … have done splendid work in a large refugee camp here”

Throughout these months, Japanese forces observed the neutrality of the International Settlement, but gradually won control of all Chinese sections in the city. The missionaries in Ningpo first heard about this fighting during their summer break and conference in the hills east of Hangchow.

As Eliza writes: “We very much realised we were in the middle of war, for not only were aeroplanes continually flying about but we could hear the thuds in the distance and at night the order was to keep all windows darkened. On our return journey … wounded men and military cars passed us and … we reached Ningpo and found the city was very empty … There is an airfield about five miles from the South Gate and the Japanese planes keep careful watch over it and bomb it at intervals … on November 12, Sun Yat-Sen’s birthday, five planes flew over the city, later they returned and dropped bombs. They missed the railway station, but the houses nearby suffered. Near the bus station there was more destruction.

“Our little English church St. Paul’s, had many windows broken by the concussion … It was decided to close the school but the sirens and planes passing made it difficult to hold classes and rumors were flying fast and furious.”

It was decided that all female foreigners should be immediately evacuated to the International Settlement in Shanghai. Eliza and Martha stayed in the China Inland Mission house. To cope with the flood of refugees escaping from the Japanese advance, 180 makeshift camps had been set up. The sisters went to work at the largest of these at Chiah-tong University, just outside the French Concession.

According to Eliza: “There were about 16,000 there during part of the winter. It was pitiful to see them. Their home was the piece of floor covered by their quilt. In some cases the neighboring families’ bedding was touching. The rooms varied in size. One large room had 167 people in it, another about 200. It was cold weather and the plea for warm clothes was insistent …”

“Some of us helped in the hospital, the sewing-room, where the tailors among the refugees were the workers. Others distributed clothes, others went from room to room to find the ones in greatest need. My sister was asked to oversee a house … and I helped her downstairs, there were about 1000 people on the ground floors. Day by day, we tried to help these poor people, especially the sick ones.”

Martha adds: “Some of the scenes must remain in our minds as the acme of bitterness and distress … Every day people died in the crowded rooms. The others who had come to the camp with nothing but a babe in their arms and children clinging to them, now saw their last treasures snatched from them by death … As one of the missionaries said ‘We felt that we had not been “evacuated” but “mobilised” by God in Shanghai to help in their time of extreme need.’”

Another eyewitness account by a fellow missionary from Ningpo reported that: “The two Miss Clarks … have done splendid work in a large refugee camp here … The refugees were so grateful for their loving sympathy and help, that they collected a sum and presented with it a silver shield. It was a most touching thing.

“Some of the people of course are destitute and others have had little money, some earned a few cents a day … The response in the camps to the preaching of the gospel is most encouraging. Chinese Christians go with foreign missionaries, and are doing a wonderful work. It is the same too in military hospitals. Chinese soldiers listen and gladly read Scripture portions, so that out of all the misery, opportunities are given for hundreds to hear and learn to read and Christians in many places are bearing witness.”

They believed God wanted them to remain and not forsake their Chinese friends and students.

In the midst of this relief work, the sisters began to hear about horrific atrocities in Nanking, less than two hundred miles from Shanghai. Over several weeks Japanese soldiers carried out mass executions of men, women and children, as well as raping tens of thousands of women. The army looted and burned the city and established a puppet government in the nation’s capital. This so-called “Rape of Nanking” sent shudders through the whole population.

The two women arrived back in Ningpo in April 1938 emotionally exhausted but were grateful they could resume work in their respective schools.

Encouraging news at this time was the reversal of government policy prohibiting religious instruction to students. This was announced by Madame Chiang Kai-shek in a publicised radio broadcast. But disturbing news was signs that the Japanese forces were now on the move towards Chekiang province.

Hangchow was the first to be attacked and the sisters were concerned for their Church Missionary Society and other colleagues when it fell to the Japanese. Concerned for their safety, word came from CMS in London advising its missionaries to leave China as soon as possible. Even though Martha and Eliza were overdue for their next furlough, they believed God wanted them to remain and not forsake their Chinese friends and students.