One of the earliest examples of Bible translation in an Aboriginal language is on display in a new exhibition celebrating Living Language.

The exhibition, at the NSW State Library in Sydney, seeks to celebrate the resilience of Aboriginal languages in a history littered with actions that sought to obliterate them.

“[Aboriginal languages] were forbidden in many places,” says Melissa Jackson, a librarian in the NSW State Library’s Indigenous engagement branch and a Bundjalung woman. “Not through laws, but through the withdrawal of food rations, or fear of corporal punishment … people in community told us that some people were arrested for speaking language,” Jackson tells Eternity.

“But through the resilience of the elders, who were secretive in the way they spoke their language, many languages are still living. We want to highlight the importance of language and its position in community.”

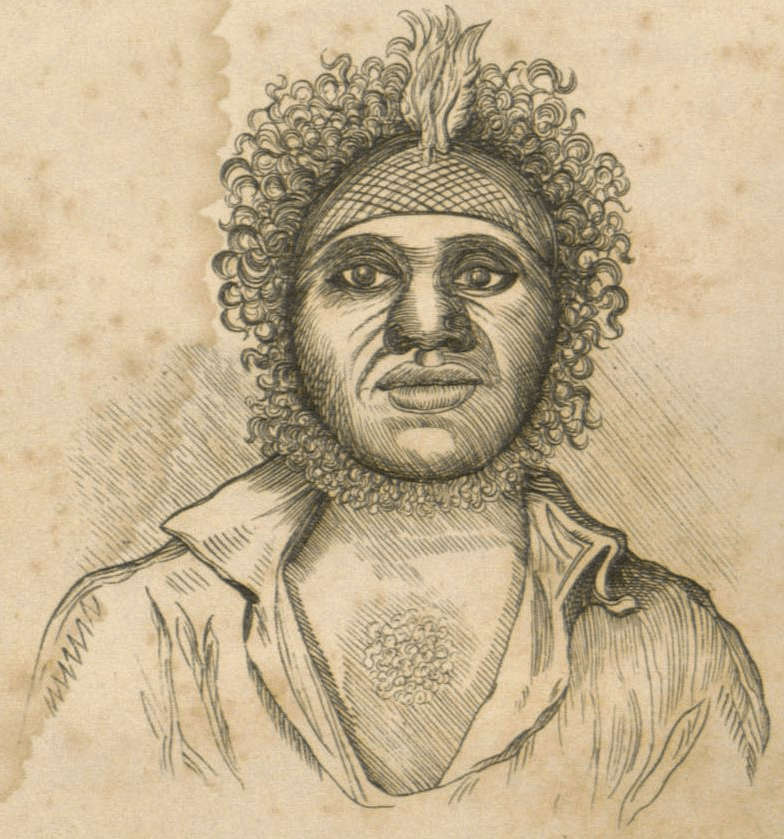

Biraban, drawn by Alfred Thomas Agate

Among stories of colonisation and assimilation policies, several early missionaries working among Indigenous Australians stand apart. One was Reverend Lancelot Threlkeld, an evangelical missionary who established an Aboriginal mission at Lake Macquarie near Newcastle on the NSW central coast (Awabakal country). It was there he met Biraban, an Awabakal man who as a child in the 1810s had been taken to Sydney to work as a servant for British officers, where he learned English. Upon moving back to Awabakal country, Biraban reconnected with his clan and also began working with Threlkeld.

Threlkeld and Biraban had “a remarkable partnership,” writes historian Meredith Lake in her book The Bible in Australia. Biraban helped Threlkeld to learn the local Awabakal language, and they together documented the language of culture of the Awabakal people and created translations of the Gospels of Luke and Mark, several Old Testament stories and morning and evening prayers.

Biraban and Threlkeld’s Bible is on display at the State Library exhibition, next to a portrait of Biraban and a notebook written by American linguist Horatio Hale, who further documented the work of Threlkeld and Biraban. It’s the first time Hale’s notebook has been in Australia since he wrote it 150 years ago. Hale’s work is recognised as “incredibly important to Aboriginal people and crucial for contemporary language revival in Newcastle,” according to the NSW State Library.

“Threlkeld wanted to communicate and Christianise the Aboriginal people, but it was totally different to the later assimilation policies that were all about telling Aboriginal people ‘you have to speak like us’,” Jackson says.

Rev Lancelot Threlkeld

The work of some early NSW missionaries including Threlkeld, as well as William Ridley in the Gamilaroi language and Anglican missionaries in the Wellington Valley translating parts of the Bible into the Wiradjuri language, saw an emphasis on speaking in the Aboriginal language rather than taking it away, Jackson says.

“The nice thing about Threlkeld was it wasn’t just about language and it wasn’t just about religion,” she says. “He really got on well with the Awabakal community. He names Biraban in his documentation – not many of the early linguists named their informants. And he appeared in court on behalf of the Awabakal people as a translator so they understood what was going on in the court setting.”

In one of his writings, notes Meredith Lake, Threlkeld refers to Biraban as “my daily companion for many years, and it is to his intelligence I am principally indebted for much of my knowledge respecting the structure of the language.”

Historian John Harris, who wrote the seminal text on Christianity and Australia’s First Nations – titled One Blood – classifies Threlkeld’s mission at Lake Macquarie – along with most other Christian outreach moves towards the Aboriginal people at the time – as a failure. He writes that was primarily because “a generation of Aborigines in south-eastern Australia were to experience the brutality and corruption of white society before the church formally responded to their need.” Threlkeld himself wrote of the violence against Aboriginal people in his reports during his time at Lake Macquarie.

Threlkeld and Biraban’s Bible, published by Bible Society

Yet, Harris credits some of the early missionaries, including Threlkeld, for their adamant belief in the essential humanity of Aboriginal people.

Threlkeld, too, believed his ministry to the Aboriginal people to be a failure. His Bible translation drafts were left unpublished until 1892 – 33 years after his death. John Harris believes the delay in publishing not only Threlkeld’s work but other missionary Bible translations was “due to a lack of understanding of the impact of translating the Bible into a person’s heart language.”

You can see Biraban and Threlkeld’s Bible at the NSW State Library as part of the Living Languages exhibition until November 17.