Simon Manchester on Samuel Marsden, whose preaching of the first sermon in New Zealand occurred on Christmas Day 200 years ago.

Marsden was probably born in 1765 and grew up in the Yorkshire area of England. The Wesleyan influence on Marsden’s parents can be seen in the fact that the Marsden boys received the same names as the Wesley men – Samuel, John and Charles.

Whatever led to Marsden’s call to ministry is not known but the financial means came through the Elland Society – a group of evangelical clergy who met to support one another and who began to fund suitable young men who were considering the ministry.

Marsden trained in Cambridge, being influenced by older men such as William Romaine, John Newton, Rowland Hill, William Wilberforce and his mentor Charles Simeon. Even in the last year of his life Simeon wrote to Marsden with great affection and warmth and in his own last year of life Marsden reflected on these great friends – almost all having preceded him to heaven.

He cut short his theological studies when the invitation came to become the assistant chaplain in New South Wales and Wilberforce recommended that he take it. At the age of 28 with his newly married wife Elizabeth he sailed for Sydney in 1793.

The men of power in New South Wales saw the role of the chaplain as “the guardianship of public morality and the maintenance of a due sense of subordination in the minds of convicts and settlers.” But Marsden was there for more biblical and eternal purposes. In fact he said in a sermon that God in his sovereignty had prompted the Americans to oppose the English in 1776 so as to allow southern peoples to hear the gospel!

From his base in Parramatta he helped Richard Johnson in the conducting of services with a desire to see all peoples transformed, morals improved and churches built. Though accused of showing no interest in the Aboriginal peoples (and he certainly found them unresponsive) he planned for their welfare and evangelism but was naive in setting up farming districts for them to settle into. Even in 1810 he was concerned for their protection and enlightenment and confident that “the glory of the Lord” would shine upon them.

A. T. Yarwood has quite reasonably suggested that finding the Australian spiritual soil – made up of officials, convicts and Aborigines – very unreceptive, Marsden turned his hopes much more to New Zealand.

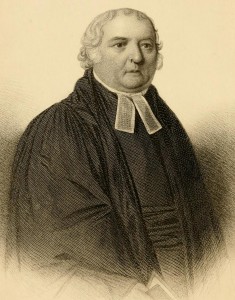

Samuel Marsden

The theology that drove Marsden’s mission and perseverance was of reformed faith from the start but it deepened and developed over the years as he suffered and found himself driven to divine promises and reassurance. He was accused of dishonesty, cruelty, greed and self-interest. It was claimed that he ran a distillery, sold guns to the Maoris which contributed to the extinction of a tribe, accumulated property beyond reasonable bounds and even became besotted with power, ending up in a “mental state” unfit for office.

It would be tedious to answer these accusations, but to take just one issue – the guns – Marsden claimed to have no gun on his own property and he considered selling guns to the Maoris as “a great sin”. He had supplied a missionary teacher with some powder for their own protection but deeply “regretted” it.

No accusation is as famous as Marsden’s hand in sentencing people to be flogged. As a NSW magistrate Marsden was expected to comply with set penalties. How much of this was done mercifully is a matter of much dispute but he wrote to his friend Miles Atkinson that he took the role of magistrate to obey the governor to bring leniency where possible. It was reported that two magistrates had ordered James Blackburn to be given twenty five lashes each morning till revealing information. Though Marsden was named as one of the two, he was in fact absent for the case, and Blackburn himself said that Marsden had not sentenced him.

It is probably wrong to play down or play up Marsden’s thinking about the benefits of civilisation. To play it down might miss the reality that Marsden thought civilisation was a powerful apologetic for the gospel. When cannibals and warriors saw life at its peaceful best they would want the source.

He longed for more of England to invade New Zealand in the cultural sense. Seeing the English flag he once said “I considered it as the signal and dawn of civilisation … I never viewed the British colours with more gratification and flattered myself they would never be removed till the natives of that island enjoyed all the happiness of British subjects.”

In one sense it would of course be utterly naïve to suggest that the simple raising of the British flag could achieve a transforming power. But in another sense Marsden was right. To communicate the gospel required some groundwork and connection. Marsden strongly believed that “nothing but the gospel could redeem” and his question was therefore “who will have the honour of leading them … to the foot of the cross?” He would write that “only the sword of the Spirit which is the word of God … can subdue their hearts to the obedience of faith.”

Iain Murray’s comment on all this may be helpful when he suggests that the early Marsden elevated civilisation beyond its powers while the older Marsden saw conversion as the only power.

What is clear is that Marsden filled his mind with Scripture and over time this illumined everything else. He could see the people who were “without hope and without God,” but he could also claim that God’s ways were hidden because “clouds and darkness are about his footsteps.”

Marsden rejoiced in the “Day Star” and looked forward to the “latter rain”. When people came to get spiritual advice he could take them all over the Scriptures. In 1830, preaching on Good Friday, he chose Hebrews 9:19-22 and on Easter Day 1 Corinthians 15:3-4 – both vital and central passages to the Easter message. He encouraged Scripture translation and when the printing press arrived the New Zealanders “danced, shouted and capered about giving vent to the wildest effusions of joy.”

So soaked was Marsden’s mind in the assurance of God’s character revealed in his Word that when his wife Elizabeth died (at the age of 63 after years of incapacity from a stroke) h

e wrote, “infinite wisdom cannot err.” When a dear friend died soon after Elizabeth’s death he wrote, “God knows and He rules over all.”

On his fourth trip to New Zealand Marsden suffered one of the most difficult and painful setbacks. The Brampton, the ship Marsden was to have left on for home, was caught in such stormy and violent seas that she had to be abandoned.

Compounding the stress under these terrible conditions, Marsden had the added burden of having with him a disobedient missionary and a difficult schoolteacher, both of whom he had removed from office. After a lonely and complicated discipline had been gently applied, everything to do with a peaceful exit from New Zealand had come crashing down. Marsden’s response was to say, “the Lord is too wise to err and too kind to afflict.”

It is hard to read the chapter in Marsden’s journal on these events without marvelling at his thought patterns, integrity, respect, steadiness, wisdom, courage and godliness as he carefully and courageously dealt with the corruption in the European workers.

Another theological theme of importance for Marsden was the idea of the great and “final Day” when all would be revealed and put right. He looked forward to this “final Day” with great confidence and joy. When reviled in newspapers or accused in the courts he could say, “the Day is coming when the Judge of all the earth would do right.”

He wrote that, “the day of resurrection will yield up God’s ways” and in the meantime “the full conviction in my own mind is that I am in the situation Divine wisdom hath placed me and this has at all times made me perfectly reconciled … I have nothing to complain of … I have no grounds for murmuring, for goodness and mercy have followed me all the days of my life.”

Launching Marsden’s Mission: The Beginnings of the Church Missionary Society in New Zealand, Viewed from New South Wales edited by Peter Bolt, published by Latimer Trust.

www.latimertrust.org

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?