The Indigenous elder who stood up to Hitler, the Prime Minister and the King – and challenged the church to pray

During NAIDOC Week, Matt Busby Andrews introduces William Cooper: The Indigenous elder who challenged all churches to pray for Indigenous people to hear the gospel.

On the morning of December 6, 1938 – a year before war broke out with Nazi Germany – the streets of Footscray were unusually windy and cold. Yet outside a cottage on Southampton Street was one of the very few bright moments of that violent century. Immaculately dressed in suits and hats, a dozen men and women, huddled together, oblivious to the fact they were making history. All they knew was they had to march to 419 Collins Street. And quickly. They were scheduled for an 11.30am meeting with Dr Drechsler, Consul General to the Third Reich.

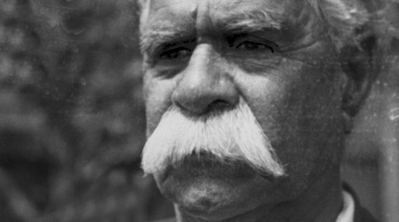

William Cooper

The marchers had decided on their message. These few resolved to protest “the cruel persecution of the Jewish people by the Nazi Government of Germany and asking that this persecution be brought to an end.”

In recent days, stories had filtered through about Kristallnacht – 24 horrifying hours that saw Hitler’s brown shirts rampage through the streets of Germany looting, burning and smashing Jewish stores and synagogues. In just a few hours, nearly 100 Jews had been killed and approximately 30,000 incarcerated in concentration camps.

Remarkably, these protesters weren’t Jewish. They were Christians. And yet, Yad Vashem, the world’s leading research centre on the Holocaust, says their protest was the only one of its kind. It didn’t happen in France or Britain or even America. It happened right here in Australia. And it was Aboriginal Australians who weren’t even citizens of their own country. They were led by a 78-year-old man from Bangerang country, named William Cooper.

William Cooper identified strongly with the Jews. When he was born in 1860, whitefellas had all but taken their land of milk and honey – the fertile country along the Murray River north of Echuca. The new white masters could be cruel as Egyptian slave-drivers – they denied Aboriginal pastoral workers their wage, and stories were told of landed men going on “blackhunts” after church picnics of a Sunday.

Amid this violence around the river, William Cooper found one place where he knew he was safe. It was on an old sacred site, called Maloga. His sister had taken him there when he was 14, and he’d met a towering white man with a long black beard, called Daniel Matthews. Here he learnt to read and write – and the great stories from the black book from an ancient people who had become slaves, and whom God, the Creator of the world, would rescue. All it took was a leader brave enough to confront Pharaoh and say, let my people go.

Following a church service in January, 1884, Cooper approached Daniel Matthews and said “I must give my heart to God….” He was the last of his brothers and sisters to become a Christian. But from there, he began a lifelong work to speak for “the least of these”, to confront governments when they were unjust, and to demand to be heard at the highest levels, from the Premier, to the Prime Minister to the King.

Cooper’s long campaign for Aboriginal rights, especially land rights, began with the Maloga Petition in 1887. One of eleven signatories, it was addressed to the Governor of New South Wales. The petition held that Aborigines of the district, “should be granted sections of land not less than 100 acres per family … always bearing in mind that the Aborigines were the former occupiers of the land.” This was 100 years before Mabo.

But it was well into his 70s, when Cooper really hit his straps. He moved to Footscray in western Melbourne in 1933. Here he found his calling as an activist, an organiser, and a relentless letter-writer.

At first this was in an individual capacity. But by 1935 Cooper had helped establish the Australian Aborigines League. As its secretary, Cooper circulated a petition seeking direct representation in parliament, enfranchisement and land rights. Knowing that (while not technically Australian citizens) all Aborigines and Islanders were British subjects, he made up his mind to petition King George V. Over several years, he and his team collected 1814 signatures, despite active obstruction from the national and state governments of the day. It informed His Majesty that:

“Whereas it was not only a moral duty, but also a strict injunction included in the commission issued to those who came to people Australia that the original occupants and we, their heirs and successors, should be adequately cared for; and whereas the terms of the commission have not been adhered to, in that (a) our lands have been expropriated by your Majesty’s Government in the Commonwealth, (b) legal status is denied to us by your Majesty’s Government in the Commonwealth…”

Cooper was effective in securing face-to-face meetings with governments. 1935, he was part of the first Aboriginal deputation to a Commonwealth minister and in 1938, the first deputation to the Prime Minister. But there was little result.

And so, Cooper’s Australian Aborigines League joined forces with Jack Patten and William Ferguson from the Aborigines Progressive Association to shame white Australia. They arranged a Day of Mourning to commemorate the sesquicentenary of colonisation, on Australia Day, 1938. The event, which was watched by journalists and police, was held in Australian Hall in Elizabeth Street, Sydney, was the first combined, interstate protest by Australian Aborigines.

By the time of his death in 1941 William Cooper had achieved almost none of the goals he had set for himself. He saw into the promised land but he did not enter it. The land he had entreated from the NSW government was at last given to his people, and his relatives live there today at Cummeragunja. His protégé, Pastor Doug Nicholls, would drive the next great Indigenous organisation, and they achieved the monumental outcome of the referendum on May 27, 1967, enabling the Commonwealth to recognise Aboriginal people as citizens.

The one success achieved in William Cooper’s lifetime was the establishment of a National Aborigines Day, first celebrated in 1940 across the Protestant churches, which he achieved through his partnership with John Needham of St Andrew’s Cathedral, Sydney. It was first known as “Aborigines Sunday” and was celebrated on the Sunday nearest to Australia Day.

We still celebrate it today, but it was moved from January to the end of May and it today is known as NAIDOC Week (

coming up in July). But the appeal that William Cooper made still stands before all Christian people:

“We request that sermons be preached on this day dealing with the Aboriginal people and their need of the gospel and response to it and we ask that special prayer be invoked for all missionary and other effort for the uplift of the dark people.”

When you trace the Indigenous justice movement in Australia back to its roots, it comes back to one man: William Cooper. It may surprise many progressives that this hero of Indigenous activism drew so heavily on his Christian faith. Equally, it may be a shock to many conservative Christians that this man, who loved the great redeeming God of the Book of Exodus, thought it his Christian duty to demand political reforms for the benefit of Aboriginal people.

But perhaps the greatest scandal is that William Cooper was so open in his challenge to Christians that we should pray that all Indigenous people know the gospel, that we become deeply aware of all the issues they face, and that we lift up our Aboriginal brothers and sisters before the world. It is bizarre that the schools and governments now mark their calendars for an annual week of awareness, while Christian churches, which actually created Australia’s day of commemoration, have all but forgotten this great man William Cooper, and the challenge he gave us all.

Note: The terms “Aborigine” and “Aboriginal” are used as the proper demonym in this article because that is the term William Cooper used when describing his own people.

This story was originally posted at Common Grace. It is published here with permission.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?