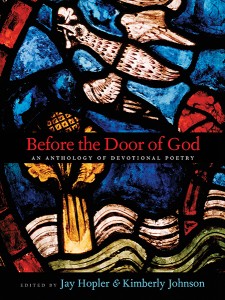

A review of Before the Door of God: an anthology of devotional poetry, edited by Jay Hopler and Kimberly Johnson. Published by Yale University Press

A review of Before the Door of God: an anthology of devotional poetry, edited by Jay Hopler and Kimberly Johnson. Published by Yale University Press

In this new anthology of devotional poetry, editor Kimberley Johnson loftily describes poetry’s traditional function as “engaging the divine”. But both readers and writers have at times been suspicious over poetry. Plato, for one, famously banished it from his ideal state. Johnson draws our attention to the poetry of George Herbert, who used it to question the ability of something as ostentatious as poetry to point us beyond itself to God. But of course in doing so in verse, Herbert somewhat undermines his own agenda. Knowingly, it seems. Poetry can be like a European rococo church, ostensibly there to glorify God, but taking attention away with the cleverness of its craft.

Despite this, the Church has a long tradition of devotional poetry, which can be defined as poetry that focuses on the individual’s relationship with God, over other communal expressions. Johnson explains that lyrical poetry lends itself to this kind of contemplation of God, as it often concerns itself with teasing out mystery. It is an individual’s response to the level of their engagement with God, an entity that we are always, like Moses, glimpsing only partially. There is a tension here, because if poetry is too personal, the reader can’t relate, but an intimate poetry can speak to us more strongly. The best of this poetry steers away from the collective “we” of the congregation, but as Helen Vendler says in her book on the poetry of Emily Dickinson (who features heavily here), the “I” of the poem can mean everyone. A major task of the editors of this volume was to select poems that exhibit this somewhat paradoxical state.

The book begins with the Psalms, which straight up muddy the waters when it comes to the definition of devotional poetry. Although they contain many an individual plea, they are traditionally recited in the congregational setting. This goes for much ancient poetry, such as the odes to Greek gods featured here. Thus the line between collective and personal is not always clear, but then, this is the nature of human existence, as thinkers from Augustine to Wittgenstein have noted.

In medieval times, there was a flowering of translations from the Psalms, and this provided the opportunity for an amount of creativity; so much so that there is more boundary blurring. It is hard to decide what is translation, and what is simply new poetry. There is a parallel here with the tradition in jazz of interpreting the standards in evermore creative ways.

Medieval England also witnessed a dramatic rise in devotional poetry in general, due to the relatively stable political situation. Then along came Luther and the Protestant Reformation, doing their part to boost devotional poetry, as they encouraged a more individual engagement with the Bible, and therefore a more personal, individual spirituality. One can find parallels in devotional poetry with Luther’s soul searching. The rediscovery of classical literature during the Renaissance also revived interest in devotional poetry within a Christian perspective. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries devotional poetry takes a dip, at least within the reformed tradition, as the “we” is emphasised over the “I”. But there is something of a resurgence with Romanticism’s reaction against the cold logic of Enlightenment thought.

When we get to the twentieth century poetry we have the strange situation of a lot of anger against someone (God) who is (apparently) not there. Poets are included in the general usurpation of God by the artist. The image of God, like that of Rolf Harris, had shifted from kindly to dastardly.

With the world wars theodicy takes centre stage, and the questioning of God’s behaviour, power or existence is somewhat easier when heresy is not punishable by death, and doubt is a default position. For believers who are confident of always hearing God’s voice, much of twentieth century poetry is an irrelevance, but for the rest of us an honest accounting of our doubts can find resonances within it. And religious belief does persist, with T.S. Eliot, Thomas Merton and more, even if the reverence of the past is gone. In the twentieth century, believer and non-believer alike are scientists, fiercely scrutinising, while poets are free to be irreverent. Mark Jarman (on the cusp of the twenty-first century) likens God to a mad driver.

Merton, a deep thinker and believer, seeks out God in the forgotten places. He writes about monks wood-cutting in a forest and finds here a kind of worship. Like a walk in the countryside, poetry can reorient by forcing us to slow down and observe differently. The challenges of modernity provoke poets. T S Eliot’s poetry at times sounds like the snippets of disconnected speech we get from turning a radio dial. Marie Howe writes about the difficulty of prayer in an age of distraction, describing the constant itch to “rise from the chair” when composing.

In the twenty-first century, where a poet can be a “meditating agnostic”, irony persists, but reverence creeps in the back door. Postmodernism is famously sceptical of grand explanations, which includes God but also includes humanity’s capacity to fix all our problems. This can induce humility and caution, and a more honest, serious tone to existential and religious issues within poetry. Everything shiny and new attracted the modernists, but twenty-first century poets are also freer to mine the traditions. Bruce Beasley, who retains faith, revels in the linguistic richness religious traditions provide, mixing this with an Annie Dillard-like fearless interrogation of the harshness of nature.

By the time we get to the modern era, Before the Door of God becomes quite American-centric (could room have been found for, say, Les Murray?). And while Hebrew is translated, medieval English is not, which, for the novice, requires some effort in the reading. And the editors have also gone for, in their words, “integrity”, and so we have odd spellings and the like, except integrity is a slippery word when it comes to poetry. Emily Dickinson, for example, scribbled her poems on any scrap of paper she could lay her hands on, and then filled the margins with amendments and alternative wordings. Later “definitive” versions of her work could be somewhat arbitrary. Just one of the difficulties of collating a very personal art form for general consumption.

Nick Mattiske blogs on books at Coburg Review of Books.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?