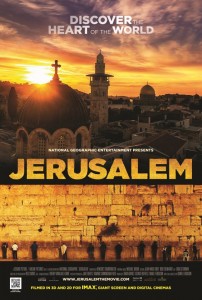

Back to Jerusalem: a new IMAX perspective on one of the oldest cities in the world

Eternity’s Kaley Payne interviews Daniel Ferguson, one of the producers of new IMAX feature ‘Jerusalem 3D’, narrated by Benedict Cumberbatch, about what he’s learned from being immersed in Jerusalem and its culture for years trying to make the film, and what he hopes others will take away from it. The film will be released at IMAX in Sydney’s Darling Harbour on April 10, with further Australian releases later in the year.

Why Jerusalem? What was the draw for you? Well, this was an idea that was brought to me actually by my fellow producer Taren Davies. I’ve done about seven IMAX films and we did a film on Mecca together, the pilgrimage to Mecca. That was an interesting experience because most of these [IMAX] films are about science education, you know, astronomy and so forth. And here was a chance to do something different. [Jerusalem] is a natural bucket list destination. I think everyone is curious about it, including myself. I studied comparative religions and history, and I thought, oh, this is interesting, but how do we do it in a novel way? There’re so many films made about Jerusalem. So I was instantly intrigued, but also terrified, trying to fit 5,000 years of history into 45 minutes, and doing it in a way that was compelling for a general audience—kids and families. So as far as why Jerusalem? Why not!? It’s a mega-subject.

As you say, a lot has been made about Jerusalem, particularly about the conflict, both modern and ancient. How do you think this film is different? Obviously, our film really sets out not to be about the conflict front and centre. Our film is about the roots of universal attachment. In a sense, it’s a way of taking a step back and saying: ‘Ok, hang on a second. Why do the Jews love Jerusalem? Why do the Christians love Jerusalem? Why do the Muslims love Jerusalem? And why is it important for you if you are not religious? What is it about this place?’ They’re all these big questions that we ask at the beginning. Why is it so fought over, coveted, and why do we read about it everyday in the newspaper, or why has it inspired so much of our culture? And I think to step back from the 21st century [conflict] is important too; not to ignore it, because it is there. I mean, it was foremost on our minds as we walked into this, and I even admit that at the beginning I sort of had this Israel-Palestine fatigue. I thought, ‘Oh gosh, how are we going to frame this in a way that people haven’t felt before?’ And so, for us it was important to look at the artistic, spiritual, cultural richness to the place…

I was particularly struck when watching the film how little of Jerusalem I actually recognised. I haven’t seem images like this in the media before—or anywhere. I guess that’s possibly because Holy Sites like the Western Wall, The Dome of the Rock, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre are notoriously difficult to get access to. And you’ve also got those grand sweeping shots of Jerusalem which were quite mesmerising. Was it difficult to get permission to make this?

Oh heavens, yes. It was one of the hardest films I’ve ever made. It’s a big headache to shoot in Jerusalem. It’s complicated; it’s sticky. You’re dealing with these groups who don’t tend to agree, even within their own religions, you know? But we kind of had to put that all aside and find a way to just cut though it all and make it really simple for the audience as a story. Some of these locations, like to film at The Dome of the Rock, for example, which is off limits to the public took us three years of negotiations and multiple trips to Jordan and into the Palestinian territories, building trust. And to get the aerials, we were the first crew in about 20-25 years to pull off low-altitude aerials over the old city. Everyone said it couldn’t’ be done. But our team were working with all the levels of the Israeli government, to the very top, to pull it off. This was a once in a lifetime chance to show the world what this city’s all about.

Why in 3D, what does it add? It’s part of the visceral nature of the city. We really designed it to work in 3D from the beginning, to create moments of intimacy as well as spectacle, and using 3D to inform people about the city so they feel like they’re there. Our aim was to make the audience the main character. It’s you, in Jerusalem. That’s the point. Ultimately it’s about how it feels for you to enter the Damascus Gate and be overwhelmed in a sensory way… I think 3D is the medium for that.

You obviously spent a lot of time in Jerusalem yourself, do you have a favourite place? Being on the top of the Temple Mount, you feel like you’re on the top of Mount Everest. Even thought the Mount of Olives is taller, and lots of mountains are taller, there’s something about being up there that you just … your heart quickens for some reason. I studied religion, but I don’t have a religious affiliation, though I’m fascinated by belief. But there’s something about being in Jerusalem, and you watch the way people imbue these stones with meaning and they have for hundreds if not thousands of years, whether it’s in the Garden of Gethsemane or the Western Wall, or at the Stone of Unction, it’s really humbling.

In this film, you’ve chosen to view Jerusalem through the eyes of a young Muslim, Jewish and Christian girl. Why did you choose that perspective? It wasn’t something we set out to do at the beginning. We knew that the perspective of young people was important … and it needed to be fresh and new.

In this film, you’ve chosen to view Jerusalem through the eyes of a young Muslim, Jewish and Christian girl. Why did you choose that perspective? It wasn’t something we set out to do at the beginning. We knew that the perspective of young people was important … and it needed to be fresh and new.

We have all these images in Jerusalem of boys throwing rocks, and protests and bearded men, so our perception is very patriarchal. But the reality is that things are changing in that part of the world. And I mean Israel and Palestine, but also the Middle East generally. Young people are going to really affect tremendous change in the next 15-20 years, and I think that women are at the front of that. I really think that any story like this where women can come to the fore and share their perspective will challenge people’s assumptions about the religions and the place. So I was totally enamoured with [these girls]. And the fact that the three girls are quite similar was a statement in itself. The fact that they wouldn’t have an opportunity to meet each other [living in separate quarters in Jerusalem] and yet they’re so similar, says something about the city as well.

One of the girls in the film says she could feel the “power and energy” of Jerusalem, do you agree with that? I totally agree with that. You don’t have to be religious to feel that. But if you just cleanse yourself in any of these holy places and you see pilgrims or residents and they come and just weep at some of these stones, as I say, it’s very moving. You do feel the power. For me, the power of the place really comes from the sense that, you know, ancestors longed for this place. You may have a had a parent or grandparent who’d always wanted to see Jerusalem, and the fact that you’re standing there makes you feel a part of history and it makes you feel a part of something bigger than your own life, and I think this is a very moving experience – that’s the secular point of view. If you’re religious, you’re communing with the divine in no short order. And that’s a powerful notion.

To make a film like this I suspect you and the other producers invested a lot personally. Do you think you came into this project with preconceptions about Jerusalem, the conflict, and its significance in the world? Absolutely. We had no idea what we were getting ourselves involved with. We were naïve about it. But I made so many trips to Jerusalem because I didn’t want to leave any stone unturned. I wanted to know the Armenian Orthodox community; I wanted to know the Mizrahi Jewish community; I wanted to know the Afro-Palestinian community. All these little groups. We invested lot of time to get it right, and obviously we chose a very specific angle, but we didn’t want to be accused of ‘oh, you didn’t show this’. I know a lot of what I left out, but I did it for a reason, to streamline the narrative and structure it in a way that people would have the sense of having travelled there and seen the land, and that the city would be set into a geographical and historical context so that we could maybe reframe the dialogue about the city. That was the goal.

Most people in the world have their own opinions about Jerusalem, about ownership and the conflict. How do you think your own perception of Jerusalem has changed in the making of this film. I think there is a need for Jerusalem literacy. We think, ‘we all hear about it so therefore we know’, but the reality is we don’t. And certainly not within these groups. I wish the girls we filmed could have seen what I saw. I was very privileged. I was invited to Orthodox, Catholic, Protestant homes, and Reformed and Conservative Jewish homes; into Palestinian homes and moderate conservative Muslims. And you just think for a second, my goodness, if everyone could experience what I’m experiencing, they’re just … I’m not even talking about peace here… I’m talking about basic dignity and tolerance and respect. Just the ability to listen. You don’t have to agree with the other’s narratives, but just be aware that it’s there. You get statements all the time from people “Why don’t the Muslims just … Why don’t the Jewish people just … Why is this so important …” And it’s from people who don’t understand and that’s what we’re trying to do in this film. You go, ‘Ah, I understand why each of them love Jerusalem’. This is a tricky business.

The sense that I got from this film is one of enormity and extremity. Such a small place but there’s so much faith, history, beauty, challenge. I did get a lingering sadness and hopelessness: how can so much be resolved? What’s one thing people see of Jerusalem through the lens of your film? It’s funny you say that about hope. I’ve had people come up to me and say, it’s great that you showed the hope in Jerusalem. And I’ve had other audiences say it’s hopeless. And I think that has to with the fact that everyone comes to Jerusalem with their own opinions and baggage. You can’t not. I think you have to give the film up to the audience. What I want is to challenge people, to step outside their comfort zone. So, if you’re a Muslim [watching this film], you get a chance to go to a Seder (Passover celebration), you get a chance to be at the priestly blessing. If you’re a Jew, you get to be at the first Friday of Ramadan. And, you get to go into a church. Jews don’t go into churches, but they can in the relative safety of this medium. I hope this film is able to slowly break some of those barriers down, challenging your assumptions about who a Muslim, a Christian and Jew is in this part of the world.

For full competition terms and conditions, click here.

For full competition terms and conditions, click here.

All images from Jerusalem 3D at IMAX.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?