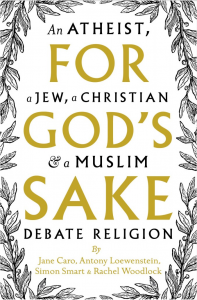

Centre for Public Christianity’s Simon Smart has co-authored a new book, For God’s Sake – An Atheist, a Jew, a Christian and a Muslim debate religion, released this month and asking the big questions of the universe. Eternity spoke with Simon about his experience in writing the book with fellow authors whose beliefs differ so fundamentally from his own.

Eternity: An atheist, a Jew, a Christian and a Muslim walk into a bar… Why get together?

Simon Smart: Lots of people have noticed that the title does sound like the beginning of a joke! A couple of years ago, Antony, Jane and I were on a panel for City Bible Forum in Sydney on the topic “Imagine no religion”. We got on well and some time after that Jane invited me to be part of the book project. We then recruited Rachel and we were underway.

I didn’t hesitate in saying yes. It was a great opportunity to be writing and interacting with people about things that matter, and it allowed me to offer an explanation of my faith to people who think Christianity is mostly weird, repressive and anti-intellectual.

You debate religion. What did that feel like? Was it uncomfortable?

Not really. I love having these sorts of discussions. The book is structured around classic worldview questions where we each give our perspective on things like, “What is it to be a human being?”, “What is the nature of the universe?”, “What is a good life?”, “How do we account for evil?” and so on.

I was glad of the chance to offer a Christian response to those questions. I am confident that when people get past the caricatures of what Christianity and Christians are like, the Christian story and the way it addresses these fundamental questions is not only logical and coherent, but enormously attractive as well. To be able to talk about that is a privilege.

Any surprises or disappointments? Were you ever on your back foot?

There were not many surprises, but it was reaffirmed for me that many people have such an incredibly negative view of Christianity and its place in our society. This represents a huge challenge to the followers of Christ. The reasons for it are complex. Partly it comes from very real failures of Christians that have been given plenty of attention. The rejection of Christian faith probably also stems from the way our society has adopted hyper-individualism as a model of personal freedom that is at odds with Christianity. But mostly the negativity stems from a popular narrative that people have bought into that would have us believe Christianity has been a force for evil and repression across the ages. From this people come to believe that shrugging off the Christian influence is part of our growing up, leading us towards enlightenment, freedom and maturity.

What I believe to be the doorway into the fullest life; the flourishing of individuals and communities, has come in some circles, to be thought of as anything but that. All the more reason for believers to be out there living out their faith in such a manner that powerfully attests to the opposite.

What was the strangest arguments that Jane Caro, the atheist made?

Both Jane and Antony are atheists of slightly different flavors. Antony is culturally Jewish but not a believer. Jane would describe herself as a feminist atheist.

I say in the book that I understand how people can be atheist— just not being able to bring themselves to believe. However what I find perplexing is the (relatively recent) phenomenon of the non-believer somehow finding ‘good news’ in a godless and singularly material universe. Both Antony and Jane speak as if the idea that there’s no God is something to celebrate. Yet, the most accomplished atheists of previous centuries, like Friedrich Nietzsche, Bertrand Russell and Jean-Paul Satre were clear-sighted enough to recognise the crushing implications of such a vision of the reality—a comfortless, meaningless, value-less universe.

It’s clear to me that the consequences of ‘God’s demise’ are serious, and I find it perplexing that others don’t recognise this, even if they can’t believe themselves.

Similarly I can’t help but wonder at a worldview that has no adequate explanation or even room to approach the question of the non-material aspects of life that are nonetheless so vitally important to each of us. These are the things in our lives that we can’t measure or touch but make life worth living. From where does beauty and goodness and love come from if our universe is just one happy accident? How do we account for the sense of transcendence we experience in music and art and relationships? In what sense can we hope for ultimate justice if this life is all there is? These are just a few of the many questions that seem unanswerable in a naturalist framework.

Rachel Woodlock, the Muslim… what was it like interacting with her?

Well in this discussion Rachel and I had the most in common. Rachel has a life-long interest in religions of all sorts, having converted to Islam via the Baha’i faith, and she has more knowledge about Christianity than the other two authors. So it was good to have Rachel there to challenge the idea that the totality of life is bound up in only material realities.

Rachel has a rather pluralist approach to conflicting truth claims of different religions—regarding these differences as only apparent. This is not by any means mainstream Islamic thought and obviously doesn’t sit with orthodox Christian belief. But it was good to identify the critical point of difference between Islam and Christianity centering on the person of Jesus. The Muslim belief that Jesus was merely a prophet and did not die on the cross and rise again is irreconcilable with the Christian belief that he was God incarnate and did indeed experience death by crucifixion and resurrection. We had to agree to disagree on that one—along with the notion of substitutionary atonement which Rachel can’t accept.

Was there something you wished you had said?

I always thought of this as being like an extended dinner party conversation. In that sort of environment there are always things you might like to say but don’t get the opportunity or realise you’ve said enough already and it’s better to shut up and listen.

I wanted to land these ideas in real life and tell stories that would illustrate what I was saying – but space meant much of that had to be left out. That’s a small regret because the ideas without real life application can lack the power that they rightly carry in people’s lives. But on the whole, I think I managed to say quite a lot and I hope it will be at least thought-provoking and attractive.

And should Christians “get out more” and interact with, atheists, Jews and Muslims? Or is it too hard?

Humans of all stripes tend to be tribal and to stick with ‘our people’. That’s understandable, but if that’s all we do it’s a recipe for disaster as our society becomes increasingly complex. It’s easy and tempting to only read those we agree with, to seek only a perspective that will affirm our positions and prejudices. We can ‘de-friend’ or block those whose views don’t gel with our own. When we do so we run the risk of effectively living in a gated community. Christian people are guilty of this for sure.

If we are going to be able to exist well together we need to spend time understanding not only the things we have in common but also our differences, and vitally, why we hold certain positions on contested issues.

Equally non-believers can find it easy to ignore, mock and dismiss those who have a strong faith. And of course getting people from different religions to play nicely together is far from straightforward. But we really must interact. We need honest, thorough and respectful engagement—and friendship. Writing this book has helped me to think that’s not too much to ask.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?