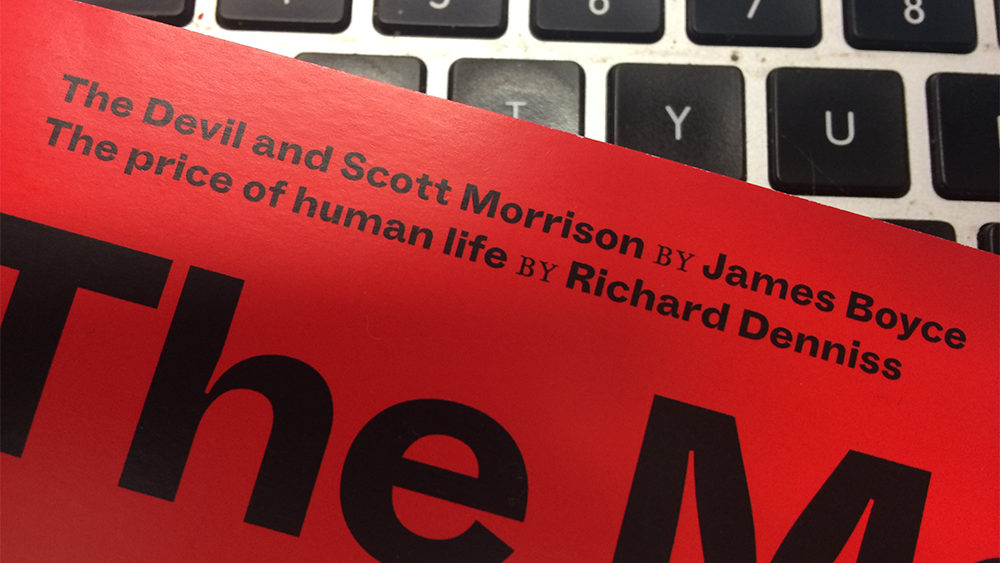

The Monthly magazine, published by Schwartz Media, Melbourne-based property developer Morry Schwartz’s mini-media empire, tries hard to get things right. Writers published by the mag have told me of rigorous fact-checking and line-by-line subbing.

So it is really disappointing that they get Scott Morrison’s Christianity disastrously wrong. Some of its errors should have been obvious to the sub-editors.

Writer James Boyce recounts the Azusa Street founding of modern Pentecostalism – describing it as a rejection of “dogma-based religion.” But eight rather chunky pars later, he describes the Australian Christian Churches’ (ACC) “non-negotiable doctrinal statement” to establish some pretty heavyweight beliefs (which we will examine a bit later).

Boyce’s take on Pentecostalism is a bit out of date.

Boyce gives himself wriggle room by saying that the ACC doctrinal statement is tighter than usual for Pentecostals – which ignores the fact that the ACC statement reflects its membership of the world’s largest Pentecostal group, the Assemblies of God.

Boyce is quite right to point out that Pentecostals (like the Prime Minister) emphasise personal experience more than reformed evangelicals. But then he links it with doctrines held by classical Christianity. These include

• Belief in a personal Devil, who is a fallen angel,

• The second coming of Christ which could happen at any time.

• Hell.

• Believers’ names written the book of life.

• Spiritual warfare and daily guidance from the Holy Spirit.

• The human species was directly created by God

It is a list that many non-Pentecostals will respond with – “we believe that stuff, too!” Hell, the personal Devil and historical Adam and Eve would definitely be on that list. Conservative evangelicals and many other Christians will be asking why their “rights” to these doctrines have been assigned to the Pentecostals. Pentecostals will be rather puzzled too.

Take the issue of the Devil as a person, not just an evil force. Many Christians will have vividly encountered this doctrine in the pages of The Screwtape Letters, the epistolary advice of a senior devil to his junior on how to best tempt a young Christian.

C.S.Lewis, the author of Screwtape, was an Anglo-Catholic, which is a fair distance from Pentecostalism.

Spiritual warfare is Christianity 101.

Boyce’s take on Pentecostalism is a bit out of date. The view that Christians are plunged into a frenzy of activity by the belief that Jesus could return immediately does describe an old-fashioned Pentecostalism. Stephen Fogarty, head of Alphacrucis, Australia’s best-known Pentecostal college, told Eternity in a recent interview that one major change in Pentecostalism is the absence of the brand of Pentecostalism that says “Jesus is coming back soon, so we don’t have to worry about improving society.” At one time the imminent return of Christ did mean that building bridges to wider society was a waste of time, but that closed-in version of Pentecostalism has disappeared.

Ironically, within the conservative evangelical world, a perceived absence of discussion of Christ’s return has led to this year’s Katoomba Easter Convention being built around the return of Christ – as a corrective to this doctrine falling off many ministers’ preaching lists.

Boyce concludes that “belief in Satan and the imminent return of Christ also helps explain the Prime Minister’s less than passionate response to the most pressing environmental issue of our time.” While Boyce is right that Pentecostals, taken as a whole, are less active on climate change than, say, progressive Anglicans, there is an emerging (but still smallish) social activism among Australian Pentecostals.

(This then gets sledged in the same issue of The Monthly in an article on Christine Caine, a Pentecostal and an anti-modern slavery activist.) But someone leaving the average Pentecostal church meeting won’t have the idea that the possibility of Jesus coming tomorrow is a reason not to make long-term plans. Pentecostals take out mortgages and plan long-term careers like the rest of us.

It is odd that practices such as “words of knowledge” and “prophecy” are not featured.

Moreover, Morrison’s handling of a lump of coal in parliament and the Coalition’s partiality for new coal-fired power stations are also in conflict with the idea that, if Jesus is coming soon, you don’t need long-range plans. Building a new coal-fired power station would take a decade or longer, for example. (This is not to endorse any particular energy policy, only to point out an obvious contradiction between trying to link the return of Jesus Christ with the Coalition’s energy platform.)

And spiritual warfare is Christianity 101. Believers of many stripes are conscious of being at war with spiritual forces, fighting temptation and the like, having read Ephesians Chapter 6, in which Paul describes the weaponry Christians need to fight in a spiritual war.

In this context, it is odd that practices such as “words of knowledge” and “prophecy” are not featured in The Monthly’s summary of Morrison’s Pentecostalism – because they are surely part of the PM’s church experience. And these are key differences – at least on the surface – between Pentecostalism and other brands of conservative Christianity.

It is predictable that Donald Trump gets a cameo role in Boyce’s analysis of Scott Morrison. “Because Pentecostals also generally believe that certain events outlined in the Bible have to occur in Israel before Jesus can return … it would be most surprising that Morrison’s uncritical embrace of the short-term political advantages of an embassy shift did not accord with what he has long believed to be the will of God.”

The hold that “end times” prophecy once had on Aussie Pentecostals has faded.

Morrison, like many Christians, will have warm feelings towards Israel, or a commitment to its survival if not ideas about a Middle East peace plan. Being pro-Israel does not have to involve a complicated theology that invokes Armageddon. At this point, it seems that The Monthly’s readers are being informed about American Pentecostals. Australian Pentecostals are not the same as their US counterparts – they share a common heritage, but the Aussies show an increasing pragmatism.

As Fogarty told Eternity, the hold that “end times” prophecy once had on Aussie Pentecostals has faded. A good place to test this out is in Pentecostal music.

Good examples of what “Christian Contemporary Music” used to produce are We wish we’d all been ready, Larry Norman’s 1969 hit about the Rapture, and Johnny and June Cash’s 1973 release Matthew 24 (is knocking on the door). Apologies to all who I have just given earworms! But it is striking that I can’t think of a similar Hillsong song with a rapture theme.

The February issue of The Monthly also contains a brief profile of Christine Caine, an alumnus of the Hillsong community who has become – as Elle Hardy’s article correctly points out – an established speaker at conferences and mega-churches in the US. The story is largely about Caine’s refusal to talk to The Monthly – although the wisdom of that becomes apparent.

(Eternity thinks Christian leaders should talk more to the media generally, but in this case thinks the evidence is that Caine made a wise decision.)

The sting in the article comes when Hardy disparages the modern anti-slavery campaign at the centre of Caine’s A21 group.

“A21 is part of a trend in the US of not-for-profits that claim to target modern slavery – although they almost exclusively focus on ‘rescuing’ women from working in the sex industry, as opposed to forced labour practices.”

Yes, modern slavery does include forced labour by refugees, people living with intellectual disability, and other vulnerable groups, and the exploitation of workers in factories in developing countries.

There is also more than a whiff of political correctness about The Monthly’s profile of Caine.

But perhaps The Monthly could have pointed out to Elle Hardy that for many women participation in the sex industry has been a “forced labour practice.”

As the February Monthly went on sale, another progressive outlet, The Guardian, published a telling portfolio by photographer Amy Romer which documented the places – in very ordinary British streets – where slaves have been kept.

This included a house in Walker Street, Rotherham, South Yorkshire, where “Fifteen vulnerable girls, one as young as 11, were subjected to acts of sexual violence between 1987 and 2003 including rape, forced prostitution, indecent assault and false imprisonment.” This formed part of a major scandal involving the sexual exploitation of more than 1400 children – a figure considered to be conservative. Action on the Rotherham grooming scandal was delayed for years due to political correctness – because a certain racial group was largely involved. There is also more than a whiff of political correctness about The Monthly‘s profile of Caine.