The ABC reports a people smuggler’s claim that the Australian Government’s latest strategy to ‘stop the boats’, ‘could not compete with the threat of death in places like Afghanistan and Pakistan that are the main force driving demand for people smuggling.’ According to Prime Minister Rudd’s new policy, all asylum seekers arriving by boat will be compulsorily removed to Papua New Guinea and will never be resettled in Australia.

This policy distances Australia, further than any other western nation, from the agreed standards for refugee protection found in the Refugee Convention, to which Australia is a signatory.

It is light years away from the Scripture’s view of the ‘stranger’:

The Lord executes justice for the fatherless and the widow, and loves the stranger, giving them food and clothing. Love the stranger, therefore, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt (Deuteronomy 10:18-19).

(I have elucidated this passage in a Centre for Public Christianity online article.)

The term that is translated ‘stranger’ here means something very similar to the English word, ‘refugee’. The tithing laws of the biblical book of Deuteronomy show what it means to ‘love the stranger’ (14:22-29; 26:12-15). Among Israel’s neighbours in the ancient Near East, a tithe of all agricultural produce was customarily paid as a tax for the benefit of the temple and its elite clergy and also the king. The tithe accumulated wealth for the privileged.

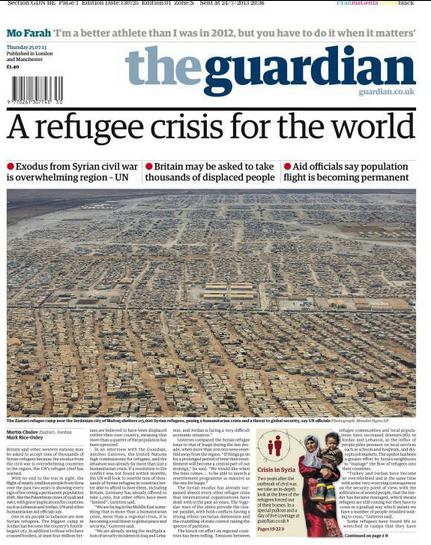

Glanville argues Australia should take stock of what’s happening with refugee crises around the world, like Syria as depicted on the front page of The Guardian newspaper in the UK in July. “In popular perception, Australia is being ‘swamped’ by asylum seekers, accepting far more refugees than its fair share. The statistics tell a different story.”

Deuteronomy turns this custom on its head, in two ways. First, instead of being taxed, the Israelite family consumed the tithe through feasting at the sanctuary—the stranger, orphan, widow and Levite joined in!

Second, every third year a tithe of agricultural produce was stored locally, for the benefit of the stranger, orphan widow and Levite. This was a costly provision for the vulnerable stranger that ensured that they too could flourish in the land. Old Testament Israel was to invite strangers into the daily life of the extended family, sharing food, farming and festivity—they became kin.

Jesus, of course, embraced the outsider. Jesus literally ate his way through the gospels. Jesus eats with all the wrong people: sinners, tax collectors and prostitutes—the unclean. Christ’s inclusive eating practices were radically at odds with the boundary-setting function of meals in first century Judaism and also Greco-Roman culture.

The fellowship meals of Jesus were a picture of messianic forgiveness, a foretaste of the Kingdom banquet to come. They point forward to a renewed humanity in rich relationship. And as Blomberg says, they call God’s people to extend ‘the intimacy of table fellowship not merely to the stranger, but also to the outcast and even the enemy.’

Aspects of the Government’s policy stand in stark contrast to the radical welcome that characterises biblical ethics. For starters, all asylum seekers who arrive by boat will be compulsorily removed to PNG, with the intention that ‘legitimate’ refugees will settle there.

PNG is a country which people flee daily as refugees. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR,) Antonio Guterres, has expressed directly to the Australian Government serious reservations regarding the suitability of PNG for asylum seekers, including that PNG is not a signatory to a number of humanitarian agreements, such as the torture convention. It is well known that PNG society struggles with issues of violence, including against women, and human rights abuses.

Or consider mandatory detention, which runs counter to the humanity of Old Testament ethics and its insistence upon an equitable social order, love for the stranger and care for families.

And what about the excision of the entire Australian mainland from the ‘migration zone’? Legal manoeuvring that leaves vulnerable people helpless is forbidden in the Scriptures: ‘Justice, and only justice, you shall follow’ (Deuteronomy 16:20).

It appears that the Prime Minister’s popularity has risen on the back of this new policy. Why? In popular perception, Australia is being ‘swamped’ by asylum seekers, accepting far more refugees than its fair share.

The statistics tell a different story. In 2011-12, the 14,620 people admitted into Australia on humanitarian grounds were only 6 per cent of the total overseas admission of 245,270. By comparison, Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, Iraq and Egypt have recently received over two million refugees from Syria. Calculated relative to GDP, Australia is ranked 52nd as a recipient of refugees (and 22nd relative to population).

Critiquing government policies is easy; finding positive solutions is more difficult. Yet positive solutions have been recommended by the UNHCR for years, centring on regional collaboration. The Bali Process, as it is called, gathers leaders and experts from the region in order to address irregular movements between countries, with the aim of stopping people smuggling and protecting displaced people.

Regional collaboration, steered by the UNHCR, is holistic and comprehensive, encompassing ‘both legal and safe passage issues while also recognising the root causes of irregular migration.’

Collaboration is essential. The Bali Process acknowledges that pathways to refugee status are very limited in the Asia-Pacific. Statistical forecasts suggest that at current rates of resettlement, placing those people presently fleeing persecution would take five hundred years! The Government’s mantra that asylum seekers should ‘wait their turn’ and pursue ‘regular pathways’ to settlement, ignores our shared responsibility to provide such pathways.

Genuine collaboration between nations in order to provide reliable and consistent access to processing and settlement has the potential to both ‘stop the boats’ and care for those fleeing persecution.

Rudd’s new policy has been criticised by the UNHCR as it erodes the integrity of regional collaboration. It also nullifies Australia’s own authority as a potential voice of reason and compassion in the Asia-Pacific. Rudd’s policy is a step backwards not only nationally, but also regionally.

Worse, to our nation’s shame, the Australian Government has chosen to disregard the hard won international agreement for the protection of refugees, represented in the Refugee Convention of 1951. Thanks to Rudd’s policy, the Refugee Convention’s authority has been diminished. This is tragic. With the erosion of humanitarian authority for ethical action we are sinking in the mire of national self-interest and the mud slinging of petty politics—Australia is experiencing an absence of moral leadership.

A way forward, consistent with both international Conventions and a biblical ethic of welcome, is to prioritise regional collaboration, as the UNHCR suggests, dealing with organised criminal networks and ensuring protection and reliable processing for asylum seekers. Meanwhile maritime arrivals to Australia are treated with dignity and respect, living within the community as their claims are processed. At the same time, Australia should heed the UNHCR’s recommendation for greater collaboration in order to minimise deaths at sea.

Biblical ethics call for a new morality in Australian politics and a new commitment among the people of God. If witness to Christ in Australia is to be authentically biblical and if it is to be heeded by compassionate Australians, then the church must carefully attend to biblical ethics regarding the stranger and both advocate for, and model, the radical welcome of Christ.

Mark Glanville, an Australian, pastors in Vancouver and studies toward a PhD in Old Testament ethics with Trinity College, Bristol focusing on the ‘ger’ (refugee) in Deuteronomy. Mark blogs at markrglanville.wordpress.com

Check out Eternity’s Federal Election 2013 Guide

Featured image: from flickr/DIAC used under CC Licence

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?