Thursday 21st November 2013

Confession?

A few days ago, I was asked to write about the Blake Prize from a Christian perspective—initially, I was rather hesitant. My initial response is ironic given that much of art in the West has been generated from the thoughts and desires of the people of the past with whom I share a common faith; however, it would also be fair to take into account the fact that we live in a different age from that of the people of the past. Faith has become a private matter. What I personally think about the privatization of faith is for another conversation. But for now, the air we breathe, namely, the privatization of faith is why I am writing this paper as a ‘confession’—I want to be honest with you. I want to be honest about my deeply held beliefs, and about the kind of person I am.

I am an artist. And, here’s a confession—I am, also, a Reverend. I take faith quite seriously. Not that I believe that ordination equates to taking faith seriously, but I hope you get my point—I am a person who constantly seeks and is deeply aware of my own need to gaze upon the glory of God in the face of Jesus the Christ, who lived and breathed on earth—just like us—about 2000 years ago in our world.

A Reverend in the World of Art

Art and religion, particularly the faith tradition I find myself in—Christianity—in our day and age, don’t seem to sit well together, at least in the public square and popular sentiment. Christianity is perceived as a bygone word of the past that has no voice; or, it’s a voice expected not to voice itself. For this reason, being a Reverend in the world of art, for me personally, has brought a whole set of unsettling feelings which I am reflecting on.

I am kind of new to the art world. In the past two weeks, I’ve had moments to be personal and open about my faith and my story to fellow artists, lovers of art, academics, and gallerists in the art community. And to my surprise, while I often met dismissal, defence or uncomfortable silence in popular sentiment, and at times, from those around me, I found myself heard, even by those who don’t necessarily share the same story and faith as me (whether that is out of their indifference or their choice). They saw me as-I-was, a person who—just like them—faces the same issues and problems in life, asking the same questions about pivotal aspects of human life where our livelihood and flourishing hinges upon—life, death, hope, despair, love, justice, beauty, meaning, and etc.

Through these personal encounters, I have come to affirm that it is only when we meet people as persons, fellow travellers on earth who carry the same weight of life’s unknowns and ambiguities—and not primarily as people marked by political, religious, ideological affiliations and titles whatever they may be, that we are able to hear and in return be heard as-we-are—and as a result flourish together as a community.

By this I do not mean that matters of politics, religion and ideologies should not be discussed openly. In fact, I think they should be, precisely because it is through these different strands of human cultures and expressions that our human pulse, however different they may be, find their unique earthy-expressions in relation to others. The point I am making, though, is that we ought to voice and hear our own hopes and fears, as well those with whom we share the world, as persons together navigating life on earth whilst meeting the same challenges of life with all its joys and pains. And, as we get to know and be known, with all our similarities and differences, we ought to find a way towards doing what we call ‘life’—together in community—and not as isolated particles randomly floating around, precisely because to be human means to be in relation to the Other.

So, despite my initial reservation, I agreed to write about my thoughts on the Blake Prize Exhibition as a person of faith.

The Blake Prize Exhibition

The Blake Prize has always sparked an interest in me, because it is an art prize that specifically engages with spirituality, religion and human justice—things I deeply care about. To my shame, I have not been to a Blake Prize Exhibition before. I am glad I made it this year. As I was walking towards the new Galleries UNSW, College of Fine Arts, many thoughts passed through my mind: ‘I wonder whether people go to this exhibition expecting to find answers for their spiritual thirst? I wonder if there would be people who break down and cry as they find some sort of release from the burdens and wounds of life? I wonder if I’d be offended by works which might make fun of my faith? I wonder whether the Spirit of God will move in me through this show?; I wonder…’

Soon, I find myself at the entrance; I open the door; I take a step in; and I start to walk around the works as they invite me, each in their own way. And to my surprise, instead of the imaginary other-worldly sentiment I was expecting—I saw things of this world: the earthy world we take part in.

I sensed: gratitude in the humility of the mundane; despair over injustice that seems to have prevailed in some parts of our world and also in our own little hearts; the pain of living in a fragmented world and the responsive-thirst for wholeness and redemption; the vastness of the wider-world which gives us perspective from time to time. And on the odd occasion there were symbolic figures and visual gestures making statements which I couldn’t understand; but, all in all, I saw stories of our own world, the world in which we exist, with frank honesty.

Overall, the exhibition affirmed what I hold to be true—that the spiritual cannot be isolated from what is material. In other words, to search for the spiritual one must start from where one is, namely one’s material existence. And this by implication means that we ought to embrace each and every one of our unique stories, precisely because it is only in and through the materiality of our world, namely, our own particular existence that we will come to encounter what is spiritual.

A Momentary Gazing

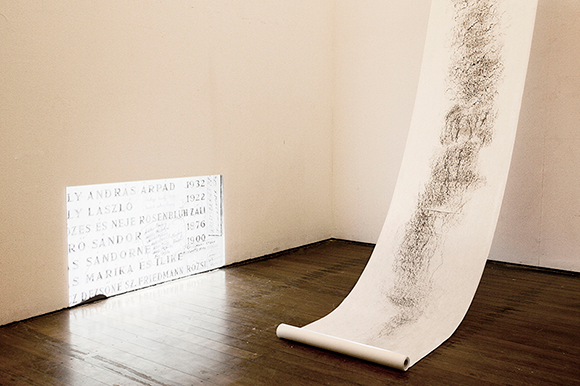

In the exhibition, there was an installation that deeply affected me. The work consisted of a video and a scroll-like paper hanging down from the top with traces of soft rubbings from a text engraved on a hard stone-like surface. I could not read what the text said; but I knew it had something important to say—perhaps one of those stories that ought to be remembered and told again and again. The trace of the stone-like surface was not complete; it was partial and it faded out faintly around the edges here and there. I felt that the text, whatever it said, was an important story that was, perhaps, on the verge of disappearing.

Soon, my eyes drifted and read the word ‘holocaust’ in the title. The words I could not read were names, actual names of people who were given life, just like me; but names that ceased to be called upon because of a tragic story that belongs to all of us—the holocaust. My heart was pierced and immediately I uttered inside, ‘He knows their names—each and every one of them”. God was near at that moment. He, through this particular work of art, turned my gaze towards his all encompassing embrace.

With a stirred heart, I quietly left the gallery—knowing that there is someone who knows all of our names, each and every one of us, even the names no one cares to remember. And quietly within me, words of my God strangely came alive: “Can a woman forget her nursing child, or show no compassion for the child of her womb? Even these may forget, yet I will not forget you. I have inscribed you on the palms of my hands.” I left the exhibition, praying to the One who weeps with us when we weep; to the One who promises to remember each and every one of our names; to the One who is deeply committed to our world for its healing and flourishing. And I asked him to hear the voices in the Blake Prize Exhibition.

Providentially, the next day, I had arranged to have coffee with Sylvia, the artist of the work which affected me. I didn’t know Sylvia well at that point, and I had never heard her story before. When I asked, Sylvia told me she had intentionally made the rubbings partial, to respect the actual people who were called by those names. There, in that moment, my heart was stirred again. I sensed the nearness of God mysteriously moving in and through all the small details of our lives, turning our gaze to him—to the One who meets us in our humanity, however marred and fragmented it may be, and takes us beyond what we can imagine and do ourselves.

Jenny Ihn is an Assistant Minister at Church Hill Anglican and is currently undertaking a PhD at Sydney College of the Arts, the University of Sydney.

Photo of the artwork published with permission of the Blake Prize, copyright to the artist.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?