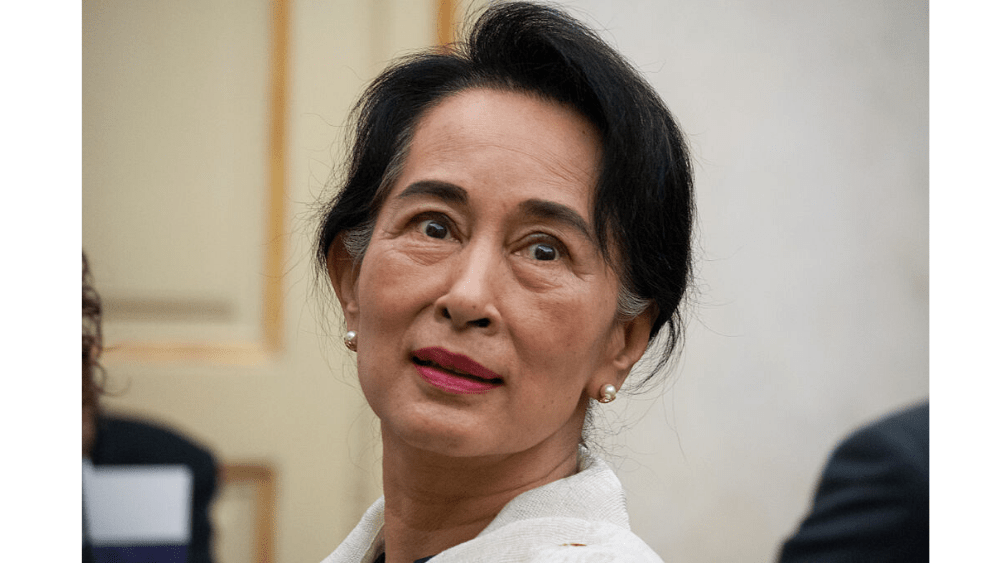

Myanmar’s Aung San Suu Kyi has faced the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in the Hague this week, defending her country in a highly anticipated genocide case.

The case attempts to bring Myanmar to justice over mass killings of Myanmar’s Rohingya Muslim minority in 2017 – alleged to have been carried out with “genocidal intent” by the country’s military.

Once the darling of human rights advocates, Suu Kyi has experienced a fall from grace over her failure to address human rights abuses as Myanmar’s de facto leader.

This week, as the country was called to account for atrocities that have occurred on Suu Kyi’s watch, she made the unprecedented decision to lead Myanmar’s legal defence.

“Regrettably, The Gambia has placed before the Court an incomplete and misleading factual picture of the situation in Rakhine State in Myanmar,” Suu Kyi told the court. “… The situation in Rakhine is complex and not easy to fathom.”

And meanwhile, in Australia, Christians are responding practically to the crisis with the traditions of Christmas charity.

The case between Gambia and Myanmar

On Tuesday, the ICJ heard details of atrocities committed by Myanmar’s military (the Tatmadaw) and associated mobs in a massive military operation in Rakhine.

The small west African country, The Gambia, which has brought the case, asserted military clearances were “intended to destroy the Rohingya as a group, in whole or in part”, via mass murder, rape and setting fire to their buildings “often with inhabitants locked inside” – all of which have been documented by the UN’s Fact Finding Mission and human rights groups.

“How can anyone possibly expect the Tatmadaw to hold itself accountable for genocidal acts against the Rohingya, when six of its top generals including the commander-in-chief, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, have all been accused of genocide by the UN fact-finding mission and recommended for criminal prosecution,” The Gambia’s lawyer Paul Reichler told the panel of 17 judges.

Making Myanmar’s case on Wednesday, Suu Kyi denied Myanmar’s military had acted with genocidal intent, instead claiming there was a language-based misunderstanding over the term ‘clearance operation’.

“In the Myanmar language, ‘nae myay shin lin yeh’ – literally ‘clearing of locality’ – simply means to clear an area of insurgents or terrorists,” she said.

But Suu Kyi urged the ICJ to allow the matters to be dealt with through Myanmar’s justice system, saying, “These are determinations to be made in the due course of the criminal justice process, not by any individual in the Myanmar Government.”

Suu Kyi argued a charge of genocide was not appropriate, given when genocide had historically been applied (against the Tutsis in Rwanda) and when it hadn’t (against the former Yugoslavia when one million residents of Kosovo were displaced in 1999, and when there was a mass exodus of Serbs from Croatia in 1995).

“Can there be genocidal intent on the part of a state that actively investigates, prosecutes and punishes soldiers and officers who are accused of wrongdoing?” she asked the court.

The hearing concludes Friday, but a final judgement could take several years.

Who are the Rohingya of Rakhine State?

The Rohingya are considered “the most persecuted minority in the world” by the UN.

An ethnic group from Myanmar, most Rohingyas live in the west-coast state of Rakhine. The area, also known as Arakan, is bordered by the Bay of Bengal to its west, the Indian subcontinent to its north and the rest of Myanmar to its east. They are primarily Muslim, with a small number who are Hindu, in contrast to the majority of Myanmar’s Buddhist population.

Historically, muslim settlers first came to Rakhine in the 1430s, and were still living there when the area was conquered by the Burmese Empire in 1784. In 1824, when the British conquered the area, it became part of British India.

The British colonists encouraged Muslims from Bengal to move to Myanmar as workers as there were no internal boundaries or restrictions between the two regions, and the conditions were advantageous for farming. The country’s Muslim population tripled and tensions flared as other ethnic groups in the region resented the influx of workers – in a region traditionally Buddhist.

Together, the Muslim workers who moved to the Rahkine and others who had been there for centuries groups identified themselves as Rohingyas – a name most likely derived from the early Muslim name for the Arakan region, “Rohang”.

In World War II, the Rohingya sided with the British who armed them to create a buffer zone against a Japanese invasion. In return, the Rohingya were promised a future independent state.

In contrast, most ethnic Rakhine sided with the Japanese.

Myanmar achieved its independence in 1948, with the British failing to deliver the autonomous state they had promised the Rohingya.

In post-war Myanmar, ethnic tensions only intensified. The same Nationalists who now negotiated for Myanmar’s independence (including general Aung San, Suu Kyi’s father) had originally aligned with the Japanese against other indigenous ethnic groups. And the Rohingya became victims of state-sponsored persecution that has continued until today.

On 25 August 2017, a group of Rohingya militants attacked the Myanmar army, causing a wave of violent retaliatory measures against the Rohingya. Violence escalated, resulting in more than 742,000 – of a total estimated 1 million Rohingyas in Myanmar – fleeing the country to seek refuge in Bangladesh.

Kutupalong refugee camp in Bangladesh. Image: Maaz Hussain By Maaz Hussain (VOA) - Source article #1, Source article #2 (direct source), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=61803429

The international community becomes involved (and what The Gambia’s got to do with it)

With reports of extreme violence and a refugee crisis unfolding in Bangladesh, the UN has stepped up its attempts to address Myanmar’s ethnic tensions, initiating various investigations beginning in March 2017.

In September 2018, the Human Rights Council delivered a report on its Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar, focused on the situation in the country’s Kachin, Rakhine and Shan States since 2011.

“The Mission established consistent patterns of serious human rights violations and abuses in Kachin, Rakhine and Shan States, in addition to serious violations of international humanitarian law. These are principally committed by the Myanmar security forces, particularly the military,” it read.

In August 2019, Fact-Finding Mission, released another report alleging Myanmar soldiers “routinely and systematically” employed “rape, gang rape and other violent and forced sexual acts against women, girls, boys, men and transgender people”.

Finally, on November 11, The Gambia filed a case against Myanmar at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague, requesting the court condemn Myanmar for violating the 1948 Genocide Convention with its campaign of ethnic cleansing.

The Gambia is a small West African country with a largely Muslim population. It was chosen to file the suit on behalf of the 57-nation Organization of Islamic Cooperation, who are covering the cost of a team of top international law experts to handle the case. And, given that both The Gambia and Myanmar are signatories to the Convention, Myanmar has been unable to refuse to cooperate with the case.

“It is clear that Myanmar has no intention of ending these genocidal acts and continues to pursue the destruction of the group within its territory,” the lawsuit read. It also accused the Myanmar government of “deliberately destroying evidence of its wrongdoings to cover up the crimes.’’

Bangladesh: Rohingyas 2015. Image: EU/ECHO/Pierre Prakash EU/ECHO/Pierre Prakash

Who is Aung San Suu Kyi

Aung San Suu Kyi was born on 19 June 1945 in the city of Rangoon (now known as Yangon) in what was then called Burma (now Myanmar) – a British colony. She was named after her father (Aung San), mother (Kyi) and grandmother (Suu).

Suu Kyi’s father was Myanmar’s General Aung San – a national independence hero, celebrated for his instrumental role in negotiating the country’s independence from Britain in late 1947. Aung San was assassinated during the transition period in July 1947, just six months before Myanmar received its independence. Suu Kyi was just two years old.

In 1988, Suu Kyi’s mother suffered a stroke and she returned to her Myanmar to care for her, after years living in Oxford in the United Kingdom where she had studied, married and had two children.

Suu Kyi spent the time studying Buddhism and political activism and her status as a nonviolent protester of the military and champion of democratic principles grew, earning her a swathe of international accolades including the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought in 1990 (pictured below) and the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991.

Presentation of the Sakharov Prize to Aung San Suu Kyi Strasbourg October 22, 2013- 14. Image: Claude TRUONG-NGOC Claude TRUONG-NGOC [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]

From champion of peace to human rights pariah

In November 2015, her party, the National League for Democracy won the national election, yet Suu Kyi was ineligible to be President due to provisions preventing widows and mother of foreigners. The President, Htin Kyaw, therefore created a new role for her – State Counsellor – on 1 April 2016, making her the de facto leader of the country.

Mark Farmaner, head of Burma Campaign UK, who helped train NLD figures in Myanmar, told the Guardian: “We knew the 2015 election was not a transition to democracy, we knew the military’s intent was not genuine, but we thought that at least Aung San Suu Kyi would move in the areas she could with a parliamentary majority: things like releasing political prisoners, repealing repressive laws, creating a free press, trying to improve the economy, environmental issues.”

“She hasn’t done any of those things. Even the limited expectations we had have not been met,” said Farmaner.

Australian Christians respond to the plight of the Rohingya this Christmas

The complexities of Myanmar and international legal battles might seem a long way from the realities of Australian life, but they will be a topic of conversation at thousands of tables this Christmas who are taking part in Act for Peace’s ‘Christmas Bowl’ appeal.

More than 1000 Australian churches across 15 denominations have pledged their involvement in the annual appeal. It involves placing a bowl on the Christmas dinner table to and asking guests to make a generous donation towards Christian work that is happening in refugee camps – including the one in Cox, Bangladesh, where hundreds of thousands of persecuted Rohingyas live.

Ayesha Khafun is a 23-year-old Rohingya woman who has been helped by work of Act for Peace who partner with Christian Aid on the ground in Jamtoli Rohingya refugee camp in Cox’s Bazaar. Ayesha fled Burma with her husband, Naser (26) and her two daughters aged 5 and 2. She gave birth to her son 16 days before leaving Burma and he died soon after arriving in Bangladesh due to the harsh cold and wet conditions. They had to flee at night in wet weather and pay the boatman with their remaining marital gold. The water levels were low so they had to jump into the water and cross the mud flats with the children. There wasn’t any food or water when they arrived, but Christian Aid has been able to provide her family with a tent, dignity kits, clothes and hygiene kits.

Ayesha is one of 25 women selected to use Christian Aid’s Community Kitchen, which is located just outside the refugee camp. The kitchen provides women with offer safe, clean cooking spaces with gas fuel and spices. The kitchens reduce the risks faced by women when collecting firewood in remote areas and reduces environmental degradation caused by deforestation. Without them, families have to cook in their tents creating smoke and fire hazards. They also function as a place for women to meet and share their stories which helps with their psychosocial well-being.

Ayesha Khafun , 23, with her family inside their shelter serving a meal of lentils she has just cooked at the Community Kitchen next door in Jamtoli Rohingya refugee camp in Cox’s Bazaar.

Christmas Bowl was launched in Australia in 1949 to help the millions of refugees suffering after WWII by Rev Frank Byatt, who, as he surveyed the abundance of his Christmas dinner, felt the strong contrast between our abundance in Australia and the needs of others around the world.

“If the Churches will not help relieve the untold human suffering of refugees in many countries, no other organisation will,” Byatt said.

“Today, 70 years since the first Christmas Bowl appeal, we are facing the biggest refugee crisis since WWII with more than 70 million people uprooted from their homes because of conflict and disaster. The call to ‘love thy neighbour’ has never been more poignant,” said Hannah Montgomery, Act for Peace, the International aid agency of the National Council of Churches in Australia that conducts the appeal.

“It is heart-warming to see that in an age of increasing division, churches in Australia from a wide range of faiths and traditions have pledged to take action together in order to provide life-giving support to people in urgent need around the world,” said Hannah.

To take part in Christmas Bowl, go to actforpeace.org.au/Christmas-Bowl/About/get-involved

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?