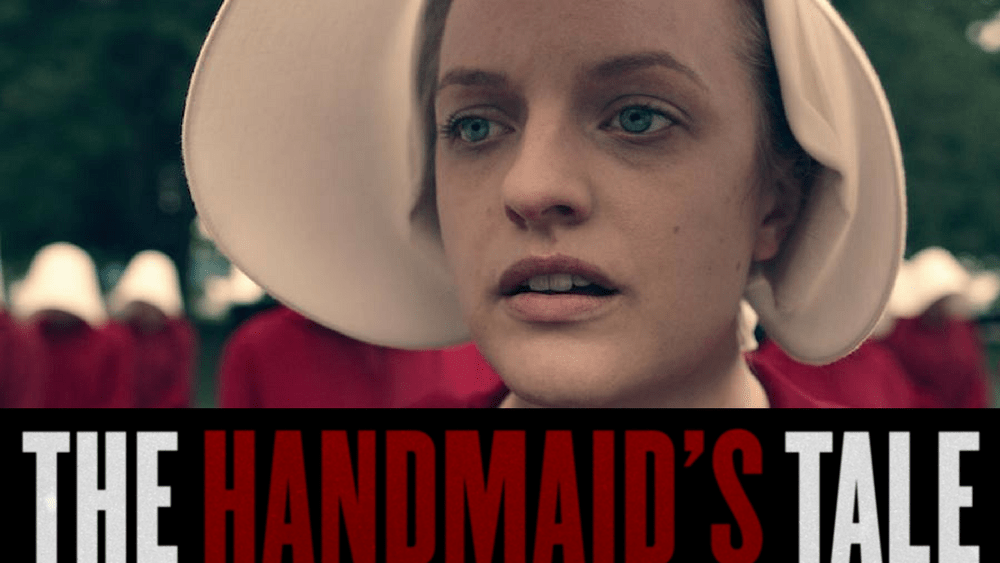

I must have read Genesis 30 half a dozen times in my life, but I never realised exactly how disgusting it was until I watched The Handmaid’s Tale. In case you’ve been enjoying life away from the 24-hour news cycle, the television adaptation of the 1985 book by Margaret Atwood follows the story of a woman who is forced into sexual servitude in a society plagued by widespread infertility.

Offred (literally Of Fred, named for the man who owns her, and with whom she is meant to produce children) is one of the few remaining fertile women in Gilead – a near-future nation in the former United States, ruled by a conservative religious elite according to strict, if not monstrously misinterpreted, biblical texts.

In response to burgeoning environmental crises, rampant sexually transmitted diseases and skyrocketing rates of “gender traitors” (homosexuals), a small but powerful faction of conservative Christians engineered an attack on the US Congress, the White House and the Supreme Court. In the naïve belief that they were “saving people” and “doing God’s work,” they instituted martial law, began stripping citizens of their rights and freedoms, and set to work building a totalitarian Christian regime that is not backward in punishing those who act contrary to the values of the ruling class.

The thing is, none of this is endorsed by the Bible.

The heart of The Handmaid’s Tale is Genesis 30, the story of Rachel and her maid Bilhah. For those who are unfamiliar with it, Rachel is one of Jacob’s wives (the other is Leah, Rachel’s sister). While Leah has borne Jacob several sons, Rachel is barren, and quite upset about it. After Leah gives birth to her fourth son, Rachel becomes agitated, and urges her husband to sleep with her maid Bilhah, to bring forth children.

The key sentence for the rulers of Gilead is, “[Rachel] said, Behold my maid Bilhah, go in unto her; and she shall bear upon my knees, that I may also have children by her.”

This verse is acted out at a monthly event, called “the ceremony”. In the series it is described as, “a sacred ritual, a wonderful ritual. Once a month on fertile days the handmaid shall lie between the legs of the Commander’s wife. The two of you will become one flesh, one flower, waiting to be seeded.” The Commander then attempts to get the handmaid pregnant. In the book it is described like this: “My red skirt is hitched up to my waist, though no higher. Below it the Commander is *******. What he is ******* is the lower part of my body.” The lingering sex scenes are enough to make you nauseous.

Handmaids are not the only ones who find themselves subjugated under the new rule of Gilead. Infertile or insubordinate women are either sent to work as Jezebels – prostitutes – at one of the city’s many underground brothels, or they are sent to the Colonies, areas of agricultural production and deadly pollution. Life expectancy in the Colonies is about three years.

“I don’t consider these people to be Christians because they do not have at the core of their behaviour and ideologies what I … would consider to be the core of Christianity … and that would be not only love your neighbours but love your enemies.” – Margaret Atwood

Even women of the upper classes experience a degree of oppression. Unable to work, read, own property or hold a bank account, they depend for their entire existence on the benevolence of their husband.

The thing is, none of this is endorsed by the Bible. Both Atwood and Bruce Miller, the creator of the 2017 television series, have repeatedly said so.

In an interview with Sojourners, a conservative church and online comment site based in the US, Atwood said that Gilead is “purportedly Christian” rather than genuinely so. Her explanation is worth quoting at length:

“I don’t consider these people to be Christians because they do not have at the core of their behaviour and ideologies what I, in my feeble Canadian way, would consider to be the core of Christianity … and that would be not only love your neighbours but love your enemies. That would also be ‘I was sick and you visited me not’ and such and such … But they don’t do that either. Neither do a lot of the people who fly under the Christian flag today. And that would include also concern for the environment, because you can’t love your neighbour or even your enemy, unless you love your neighbour’s oxygen, food, and water. You can’t love your neighbour or your enemy if you’re presuming policies that are going to cause those people to die.”

It’s easy for Christians to get defensive about The Handmaid’s Tale and to feel it is a personal attack on the Bible and the God they love. Atwood uses an admittedly uncomfortable passage from the Bible to speculate about various social, political and religious trends of the 1980s, particularly focusing on “casually held attitudes about women,” and what would happen if those attitudes were taken to their logical end.

It’s no big secret that women have often been subjugated in the name of Christianity, whether or not the beliefs of the group actually derive from Christ.

Her prediction is horrifyingly plausible. That might be because, when writing the book, Atwood restricted herself to events that had happened, although not always in the same combination as portrayed in the book and television series.

For example, the Quiverfull community, which has chapters in the United States, Canada, New Zealand, Australia and the United Kingdom, and whose rules are based on the King James’ version of the Bible and Psalm 127, espouses traditional family values, with an emphasis on having lots of kids. Women are not allowed to have email or bank accounts, or even leave the house without their husband’s permission. Sound familiar?

Hannah Ettinger, who escaped from the Quiverfull community a couple of years after marrying within in, says that reading The Handmaid’s Tale helped open her eyes to the possibility that women could have rights and lives of their own. Having said that, she saw in the book, “a fictional world [that] sounded a whole lot like my real life … when I read it for the first time, it felt like a prophecy that echoed rhythms of the world I had been raised in, reflecting the vision my church and community had for the future of American culture and politics,” Ettinger wrote after leaving Quiverfull.

But The Handmaid’s Tale is also historical. It’s no big secret that women have often been subjugated in the name of Christianity, whether or not the beliefs of the group actually derive from Christ. In fact, if you read the Bible badly, you can find dozens of ways to oppress all kinds of people. (It needs to be said that even though this kind of subjugation and oppression is not the comprehensive view of Scripture, that has not stopped some human leaders in the church acting in ways that diminish the roles and value of women, and others.)

Perhaps this story suggests we are destined to keep making the same ugly mistakes in a never-ending loop. Or perhaps it shows us that, left to our own devices, we can never break the cycles of oppression and violence – we will always be drawn to seek power, and be tempted to use whatever means are available to us to get it. Perhaps most of all, it uncovers our need for leaders bathed in humility, who run from power and refuse to lord it over others, and who look to govern for the good of all.

Watch Eternity’s Ben McEachen discuss The Handmaid’s Tale: