Let me start with what may be a controversial statement: The gospel of Jesus Christ demands social justice but working for social justice is not the gospel.

One of the great divides that emerged in Christianity in the 20th century was the division over the place of what we may call “social justice.”

Recently, that division has become even more pronounced. A group of US evangelical leaders produced a statement called “The Statement on Social Justice and the Gospel.” This statement has produced a good deal of controversy.

Although it repudiates racism as a grave evil, it seems to minimise the need to change laws, systems and cultural attitudes that promote it.

It argues, for example: We deny that political or social activism should be viewed as integral components of the gospel or primary to the mission of the church … We deny that laws or regulations possess any inherent power to change sinful hearts …

It goes on: We emphatically deny that lectures on social issues (or activism aimed at reshaping the wider culture) are as vital to the life and health of the church as the preaching of the gospel and the exposition of Scripture. Historically, such things tend to become distractions that inevitably lead to departures from the gospel.

The statement has been sharply criticised by conservative evangelical leaders such as Al Mohler for its attitude to race and racism. Although it repudiates racism as a grave evil, it seems to minimise the need to change laws, systems and cultural attitudes that promote it.

The evangelical movement always had, alongside its belief in the necessity of personal conversion, a passion for social reform and issues of justice. Great heroes of evangelicalism include William Wilberforce and William Carey, just to name two. There was no doubt in their minds that the gospel of Jesus Christ compelled Christians to do good works – and that this included changing social structures, where necessary and possible, to provide more compassionate and humane outcomes for all people.

To this way of thinking, Christians are doing gospel work when they argue for racial equality or promote more just treatment of the poor, regardless of whether the gospel is preached or not.

Later on, though, the divide emerged between those who were committed to personal conversion through evangelism as the supreme, even only, calling of the church, and those who argued that the Christian gospel was advanced as much by social justice as by evangelism.

In the 1920s, a Baptist pastor called Walter Rauschenbusch argued that the Christian gospel was really about extending the kingdom of God. He criticised what he felt was a narrow focus on personal conversion. For Rauschenbusch, this was disastrous, because it meant that we missed the devastating impact of sin and evil on and through social structures.

For Rauschenbusch and those he influenced, the church’s mission was to bring in the kingdom of God by social action primarily – and indeed, almost exclusively. So, to this way of thinking, Christians are doing gospel work when they argue for racial equality or promote more just treatment of the poor, regardless of whether the gospel is preached or not.

On the other side of the ledger, you find someone like D.B. Knox, former principal of Moore College in Sydney, who argued that there was no such thing as “social justice” in the Bible. Christians were called to compassion (and he was a fine example of that) but seeking to reform social structures was not their mission. Our task is to preach the gospel, and when hearts are changed we find that society is changed. This is very similar to the approach of the “Statement on Social Justice and the Gospel.”

Without love – and that love expressed in practical compassion and generosity – the gospel has not taken root in a person’s heart.

As you can see, this has been a polarised – and polarising – debate. And I think it takes careful navigation to see the way forward. We need to define and explore the terms we are using, and to be aware of how we may be misheard. We also need to work from Scripture rather than from sentiment or from fashionable politics, left or right.

The first thing to say is that the gospel of Jesus Christ calls on us to love our neighbour, and even our enemy, as ourselves. Nothing could be clearer than that. Without love – and that love expressed in practical compassion and generosity – the gospel has not taken root in a person’s heart. We have not heard Jesus at all, and not understood the gospel of forgiveness of sins through his atoning work on the cross, if we are not concerned for the poverty, loneliness and pain of our neighbour.

God’s peace, his “shalom,” is his vision for the created world living in harmony with him.

Often, arguments about social justice and its relationship to the gospel make it too complicated. Are not Christians commanded to “do good to all, and especially the household of faith?” (Gal 6:10). It is surely unarguable that Christian obedience demands us to seek justice – especially when, as is often the case, we have more power to change the structures of society than early Christians did.

We could make the theological point even more profoundly by appealing to two Old Testament concepts: peace and righteousness. God’s peace, his “shalom,” is his vision for the created world living in harmony with him. His righteousness, likewise, is not the same as “justice” as an abstract balancing of the scales, but rather something like “everything in right relationship, especially to God.”

That means we cannot think of discipleship in simply individual terms.

We see extraordinary pictures of God’s peace and his righteousness in the book of Isaiah, especially from chapters 40-66. These two concepts are interesting because God is at the centre of them. They involve right relationship or harmony with God first and foremost. If we have God’s heart for the world, we will want to see his peace and his righteousness reign, but especially that comes about as people are reconciled to the creator.

The second point is to do with sin and evil. Rauschenbusch was right: sin is not just individual; it is social. But it would also be a distortion to say that it is only social. The Bible gives us both: Jesus dies for our individual sin, for us as individual sinners. And he also dies to triumph over the powers and principalities that are arrayed against God. Human beings collectively and individually sin.

And that means we cannot think of discipleship in simply individual terms. Neither can we think of the Christian gospel as only a matter of the individual’s reconciliation with God. But if it doesn’t begin with the individual’s reconciliation with God, it is not the gospel of Jesus Christ.

Jesus did not just die for sin. He died for sinners.

But “social justice” as it is used in common parlance has the flavour of a progressive and highly secular political vision.

Thirdly, we need to recognise that the term “social justice” is particularly loaded and needs clarification. At face value, the good news of the rule of Jesus Christ has always implied “social” “justice” – that is, it always creates and commands a new form of common life. The church itself is to embody life with one another and with God based on grace and peace. From the earliest times, the church shared its goods in common and overlooked social distinctions. Slaves and masters, men and women, Jews and Gentiles, poor and rich all worshipped side by side. They were to find harmony in difference and to lay down their rights in order to build one another up. That’s God’s vision of a renewed humanity, gathered together on the basis of the forgiveness of sins in Jesus Christ.

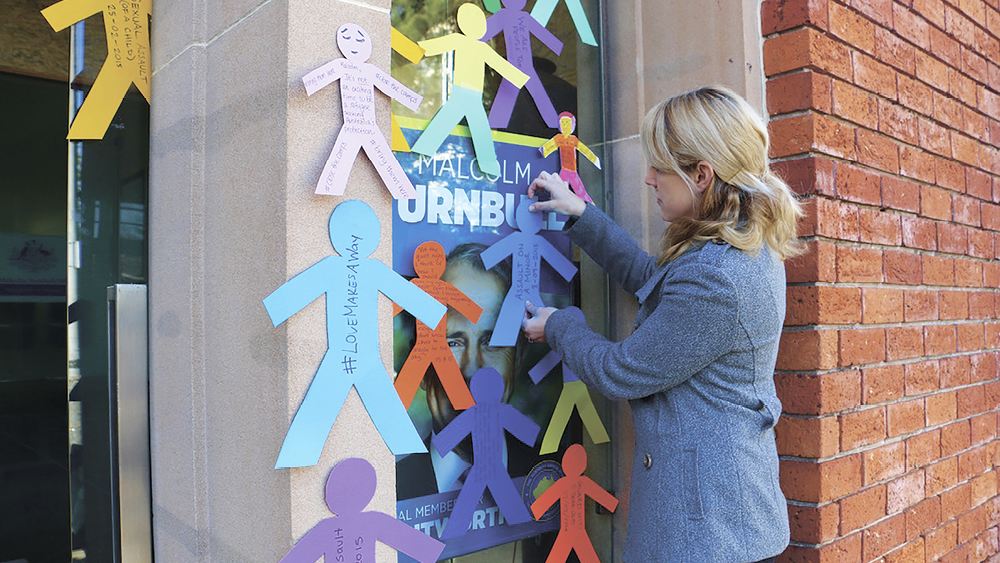

But “social justice” as it is used in common parlance has the flavour of a progressive and highly secular political vision. This is where great care needs to be taken when Christians use it. The gospel imperative to practise social justice may be attached to a number of different political programmes. Is it more socially just to have more taxation, or less? Is it more socially just to defend traditional marriage, or to allow people freedom to marry a person of the same gender? Is it more socially just to increase welfare or decrease it? Is it more socially just to give a social advantage to historically oppressed minorities, or does it just further deepen their dependence on identity as victims?

It is shameful when the people who belong to Jesus are indifferent to injustice.

These are all very serious and important questions – and there are answers that are more or less Christian. But a particular vision for how justice is to be implemented in a given society at a certain moment in history is not the same as the gospel of Jesus Christ.

I take issue with the “Statement” because obedience to the gospel demands that we think about social justice. It is vital to our health as a church, if we are to be obedient to our Lord.

It is shameful when the people who belong to Jesus are indifferent to injustice. Compassion (for example) was not enough in South Africa under the apartheid regime – which had been justified by a dubious reading of the Bible. The word of God needed to be spoken and lived into that situation, to name its evil and to expose its terrible hypocrisy.

But I do agree that we can too easily substitute working for social justice for the gospel – in which case we just become a reflection of whichever political philosophy we prefer, progressive or conservative. The power of the Holy Spirit to change hearts, by drawing repentant sinners to the cross of Jesus Christ and by unleashing his resurrection power in them, is the power we wield for change.

Michael Jensen is the rector of St Mark’s Anglican Church in Darling Point, Sydney, and the author of several books.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?