Australia doesn’t have a “welfare problem”. What we have is an inequality problem. And there’s some clear reasons for it.

First, secure and affordable housing is becoming harder to find. With the Australian housing market among the most expensive countries in the world, social housing waiting lists have swelled to 180,000 households. Yet public investment in social housing is at an all-time low.

Housing un-affordability continues to cause a wider range of people to become homelessness than ever before, including older women and tertiary students – members of the ‘middle classes’.

Housing un-affordability continues to cause a wider range of people to become homelessness than ever before, including older women and tertiary students – members of the ‘middle classes’.

Results of the most recent census in 2016 show the number of homeless people is growing significantly. It estimated that 116,427 people were homeless in 2016, which was an increase of 13.7 per cent compared with the 2011 census, which was a 14.2 per cent up on the 2006 census. It’s likely those numbers have climbed since then.

Changes in the job market have also had a big impact. Jobs growth was almost stagnant from 2008 to 2017 due the Global Financial Crisis, and there’s currently only one job for every eight job seekers. In addition, the share of low-skilled jobs is gradually shrinking, which is making it even harder for people who are already unemployed to compete for jobs.

On top of that, those who need assistance have had it reduced. The unemployment benefit has not been increased in real terms since 1994, and anyone who is dependent on the payment has to live on just $39 a day. Overall these trends have meant that poverty is very much an Australian reality. A recent ACOSS report found there are more than three million people (13.2 per cent of the population) living below the poverty line, including 739,000 children (17.3 per cent).

Yet grumbling about welfare recipients has become a national pastime.

I’ve found the way the wider community blames people for being left out or locked out – as if poverty is somehow a personal choice – most troubling.

I’ve worked at both ends of the service spectrum – in community development with rough sleepers and public housing residents in Sydney’s inner city, and also at the policy level developing homelessness strategy for government. And I’ve found the way the wider community blames people for being left out or locked out – as if poverty is somehow a personal choice – most troubling.

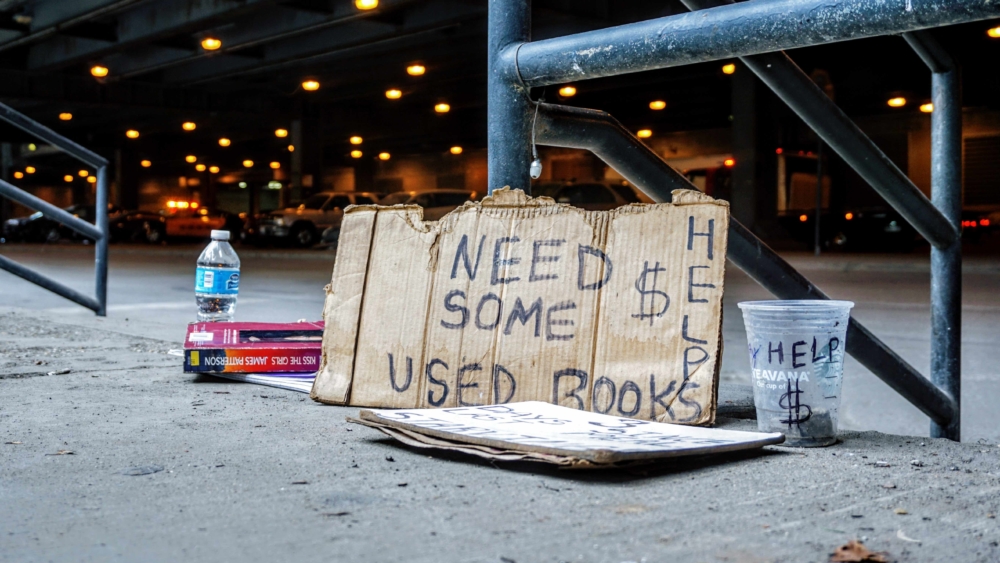

The public seems to misunderstand why people end up without an income or a home, and explains away the persistence of homelessness by stigmatising and demonising those most in need. “Dole bludgers”, “leaners”, the “taxed nots” are just some of the names we use to refer to a growing group of people in our local communities who are struggling and living below the poverty line, surviving on charity and government welfare payments.

Although homelessness has increased across the nation, a person’s poverty and reliance on social security payments is still too-often framed as a personal failure, rather than the result of deficits in our social and economic systems which make homelessness impossible to avoid for many people.

I’m encouraged by a number of individual churches that have been working for decades to provide support and assistance to people who are doing it tough, with Wayside Chapel in Sydney’s Kings Cross probably the best known.

Every day, the CEO of Wayside, Jon Owen, and his team see and touch the Australian face of marginalisation. Owen speaks eloquently about the need to avoid the twin traps of pathologising people as either “sick” or as morally bad.

“We need to rethink the language we use around homelessness,” he recently wrote in his weekly Inner Circle blog post. “On our website, we say that we ‘live on the intersection between love and hate, the intersection between faith and no faith, between the haves and the have nots, the housed and the homeless, the sick and the well.’

“That’s why we offer a judgment-free space. We welcome all who come in, some on the worst days of their lives, not as a problem to be solved, but as a person to be met.”

Why, then, are so many people living below the poverty line, and so many without a roof over the heads? Because we accept it.

Perhaps a focus of the bigger picture is what is needed. The problems facing these communities are incredibly complex, and are often both material and psychological. Childhood trauma can make life overwhelming. Losing a job, living with a disability or mental illness, or leaving a violent partner can quite easily push someone into homelessness quickly and unexpectedly. When one or two things go wrong, the effects can snowball and bury you alive.

We live in a rich country that enjoys enormous wealth by global standards, and an economy in which there is enough for everyone.

Why, then, are so many people living below the poverty line, and so many without a roof over the heads? Because we accept it. We are in denial about how easily it could happen to any of us.

Australia doesn’t have a welfare problem; we have an inequality problem. Isn’t it time we rethink who we are blaming, and consider how we can invest in people and communities so that no one misses out?

Natalie Lammas Williams is a social policy adviser and the Chair of Common Grace. She will be moderating aconversation with Jon Owen, CEO of Wayside Chapel, at ‘What’s the Story,’ an event being held at the Williams Street Studios in Fairlight, this Saturday 10 November, 7.30pm.

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?